50 Years a Cartoonist

RESEARCH LEGACY: personal reflections on a career in research

Louis Hellman - cartoonist, satirist and architect - reflects on a long career chronicling the architecture profession and its foibles. His research into the occupants' perspective, architectural practice and the drivers that influence the built environment resulted in a powerful, insightful critique of the built environment and a moral compass to the architectural profession.

It’s October 1967. The “Summer of Love” is over, signalling the end of the hippie dream of a world in love and peace, UK Labour prime minister Harold Wilson assures the public that the devalued pound in their pocket is still worth a pound and yet another (abortive) scheme to extend the Palace of Westminster in London is unveiled. The following year a gas explosion in an East London council block—Ronan Point—causes the prefabricated external wall to collapse, kills four tenants and one of the main (precast) planks in the modern movement’s edifice of precepts starts to crumble. What better time to start publishing satirical cartoons on architecture and the built environment?

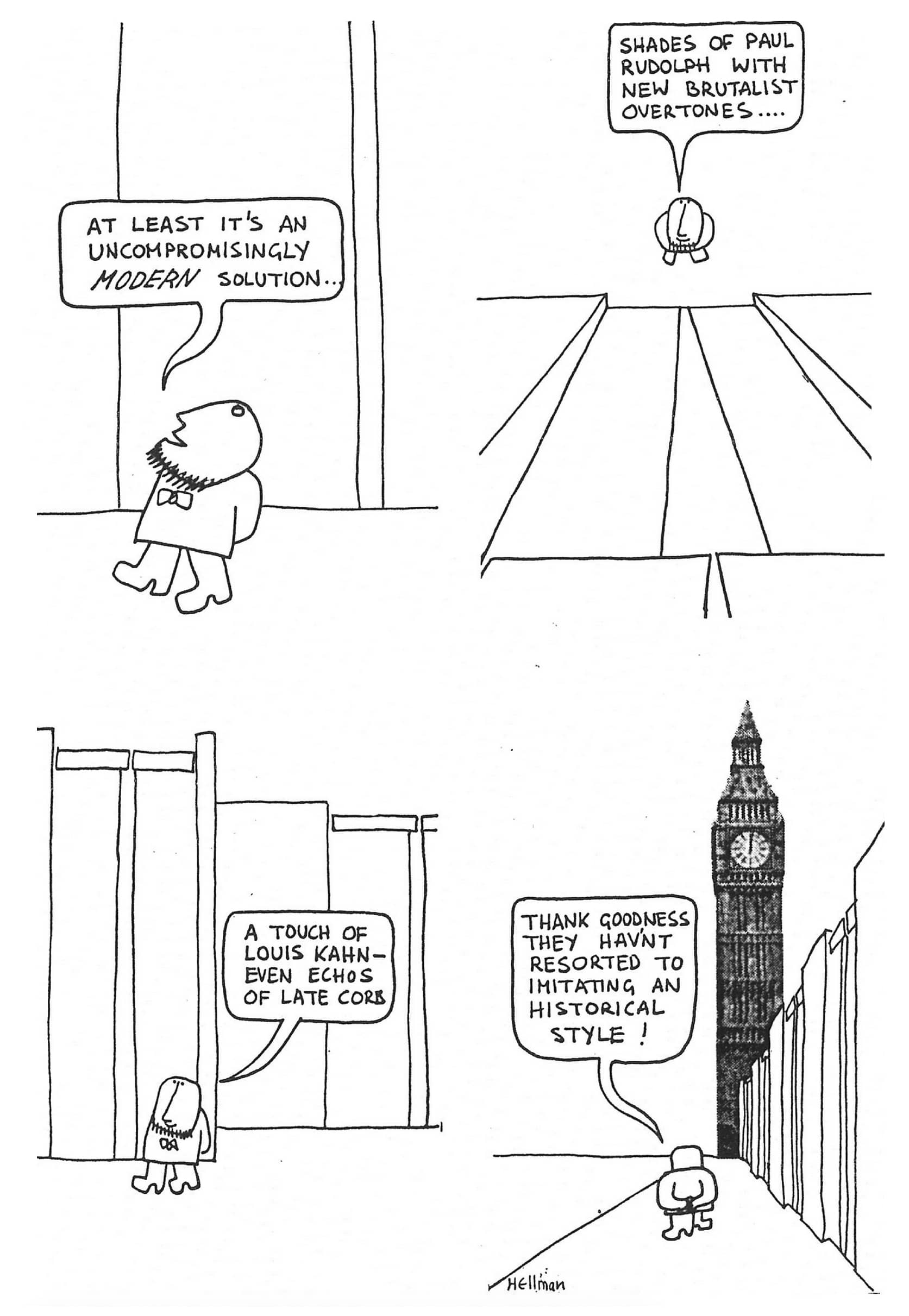

I have always drawn cartoons from my childhood during WW2, as a student at the Bartlett School of Architecture, and when I qualified as an architect. At the Bartlett I had fought for modern architecture in the face of a reactionary and heritage-based course at that time and took on board the precepts of the modern movement, a rejection of historic styles and an acceptance that the exploitation of advanced technology would evolve new functional forms to serve the people. However, when I joined a prominent modernist architectural practice in 1964, I quickly realised that these ideals had been hardened into a dogma or set of shibboleths. In effect, it had degenerated into another style to be forced through in the face of reality and economics.

My way of expressing my disillusionment was through the medium of the strip cartoon. I would note down the dogmatic modernist shibboleths heard in the office and turn them into strips with a beginning, middle and an ironic end. The speaker was a small, rotund, bearded, bow-tied architect who became my stereotype architect image from then on—an instantly identifiable passive character who can react to events. Of course, there is much of myself in the character. My first cartoon for Architects Journal (AJ) appeared 11th October 1967. The news item was the proposed lumpen extension to the Houses of Parliament, one of many to come and the Ministry of Public Building and Works was the culprit.

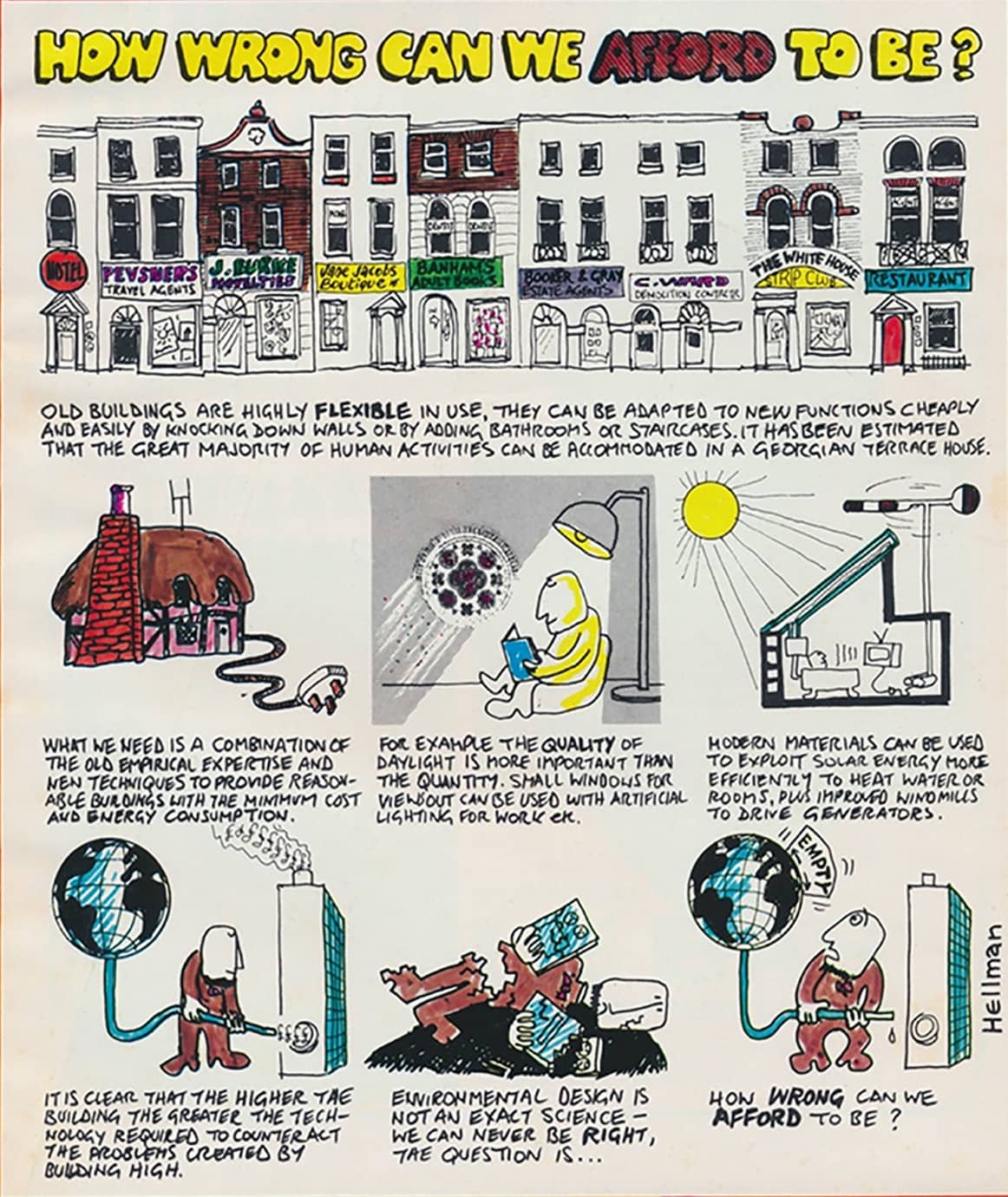

In the intervening decades I have tracked the demise of high-rise, the bruising of New Brutalism, the less than spectacular Neo-vernacular, the posturing of Post-Modernism, the thrashing of the profession from Thatcherism, the dogma of speculative developments, the chagrin of Prince Charles, the conundrum of Community Architecture, the compulsion of computer-aided design, the decompositions of Deconstruction, the neologisms of New Labour neophytes, the hegemony of Hi-Tech, the bluster of Blobitecture and the sophistry of sustainability. My first cartoon about the threat to the planet’s wildlife was in 1969 and others followed such a “How wrong can we afford to be?” about energy conservation on the cover of the Royal Institute of British Architects Journal (RIBAJ) in 1976. We have known about environmental degradation for over 50 years and architects have been slow to act.

In 1967 I joined the Greater London Council (GLC)/Inner London Education Authority’s school’s division known for designing schools to meet the new progressive educational requirements. These large local authority architectural offices which evolved after the war with huge socially responsible programmes of work usually with minimal funding. Although I encountered distressingly patronising attitudes at the GLC, “People might know what they want, but we know what they need!” The “people” were never asked.

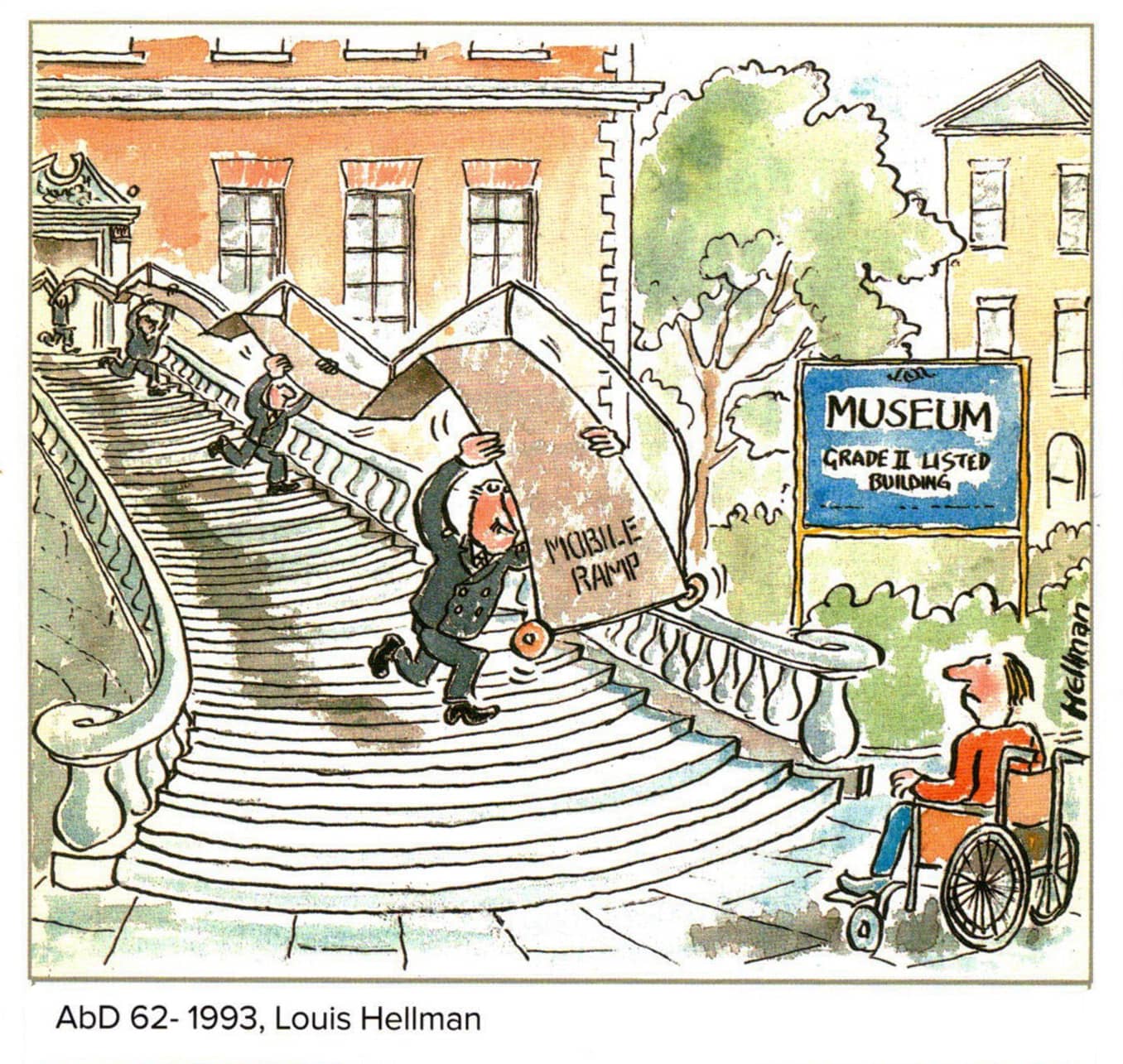

Having battled against the GLC over the imposition of a quite inappropriate prefabricated schools, I left under a cloud to join the Spastics Society (now Scope) architects department in 1974. I had little knowledge of designing for disabled people, but it seemed to represent a life-affirming architectural service for those unable to deal with the so called “normal” environment of long flights of steps, thresholds, narrow doors, toilets and lifts, not to mention the wider built environment. The architectural profession had not considered these needs, designing for an average, able-bodied, white, heterosexual male who probably does not exist. No account was taken of wheel-chair users, elderly or infirm people, parents pushing buggies, carrying shopping, obese or very young, visually impaired and so on, and thereby ignoring around 50% of the population. I now realised that architects were not designing for non-average people, but not designing for people at all.

When I started publishing cartoons critical of modern architects and their work I tried to stand back and view the buildings as a layman, free of the professional jargon that was used in justification. I found that many buildings were brutal, inhuman or just downright ugly. Lay people’s comments such as “Concrete jungle”, “Looks like a prison” or “Rabbit hutches” I found to have some validity. I attempted to step outside the blinkered eyes of the professional and the myth of the “average” user with the desire to see buildings as a lay person does and aimed to satirise the professional jargon and art-speak that was designed to obfuscate the public's understanding.

My attitude, approach and style changed somewhat in the 1980s. There seemed to be so much happening in the real world that impinged on architecture and, now self-employed, I turned my sights onto political figures rather than the arcane internal manoeuvrings of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and the profession generally. Prime minister Margaret Thatcher and Prince Charles were wonderful sources of satire and humour as was Post-modernism with its simplistic silliness and stupid semantics.

Prince Charles took over the role of applying dumb epithets to modern architecture and I began to feel slightly sorry for the profession. In 1984 he made his famous speech for the 150th anniversary RIBA celebrations. Many of the generalities in this speech were about architects and planners being out of touch with “ordinary people,” which I applauded. But then he attacked current projects under planning review—which severely damaged the reputation of the practices concerned and constituted royal interference in the legal democratic planning process. Charles later nailed his colours to the mast of traditional architecture and neo-classicism, fuelling a spate of mock Victorian housing, mock medieval supermarkets or mock Georgian office blocks. Thatcher’s government was the parallel 1980s influence on architecture: it made a bonfire of the regulations; abolished local authority architectural departments with their engineers, valuers, building surveyors and quality control officers; abolished fee scales for architects; waived planning permission in development zones; ended council housing and sold off the better examples on the open market for speculators to purchase. Other public sector architectural departments were privatised and competed in the market for work. It was every man (yes, man) for himself. Today we are paying the price for all this in terms of the crisis in affordable social housing and lack of standards control.

As I was also a practicing architect the accusation could be levelled “What are you doing that's so much better?” My barbs may, however, have contained a pinch of self-criticism and self-education. My own approach has always been to stress the political role of architecture, something rarely referred to in higher education or in professional periodicals which tend to be confined to their hermetic inward-looking world. To construct any building requires relatively large resources whether an office tower or private house. Those with such resources are inevitably wealthy and powerful individuals or corporations used to getting their own way and over-riding rules and planning constraints. That’s a fact of architecture-architects need work to survive and that’s where the work is. Architecture has no moral imperative, no moral compass or scale despite its pretentions to improve society or the environment. Here is a rich source for cartoon satire by exposing how architects serve power elites or build for all sorts of totalitarian regimes—so I often draw the architect as a kind of poodle of the rich and powerful and of regimes.

My style changed to resemble political cartoons in newspapers when the AJ wanted cartoons related to topical news items. Now I started satirising actual architects and buildings, honing my skills as a caricaturist. Criticism of a fellow professional was frowned on and I frequently received hostile or abusive letters and there were occasionally angry responses from my 'victims' as well as a few incidents of writs being served on the editor by the more powerful practices by architects objecting to cartoons which claimed they questioned their client's professional ethics. It was always settled out of court with a sum paid to a charity. Although my relationship with the AJ blew hot and cold, they generally always published the cartoons however offensive they might be. A few times they refused to publish arguing that they might upset advertisers. There was also some censorship of the cartoons when I had to change the wording, and their lawyer who vetted the drawings always erred on the side of safety. Today I submit a rough sketch for approval to avoid any conflicts.

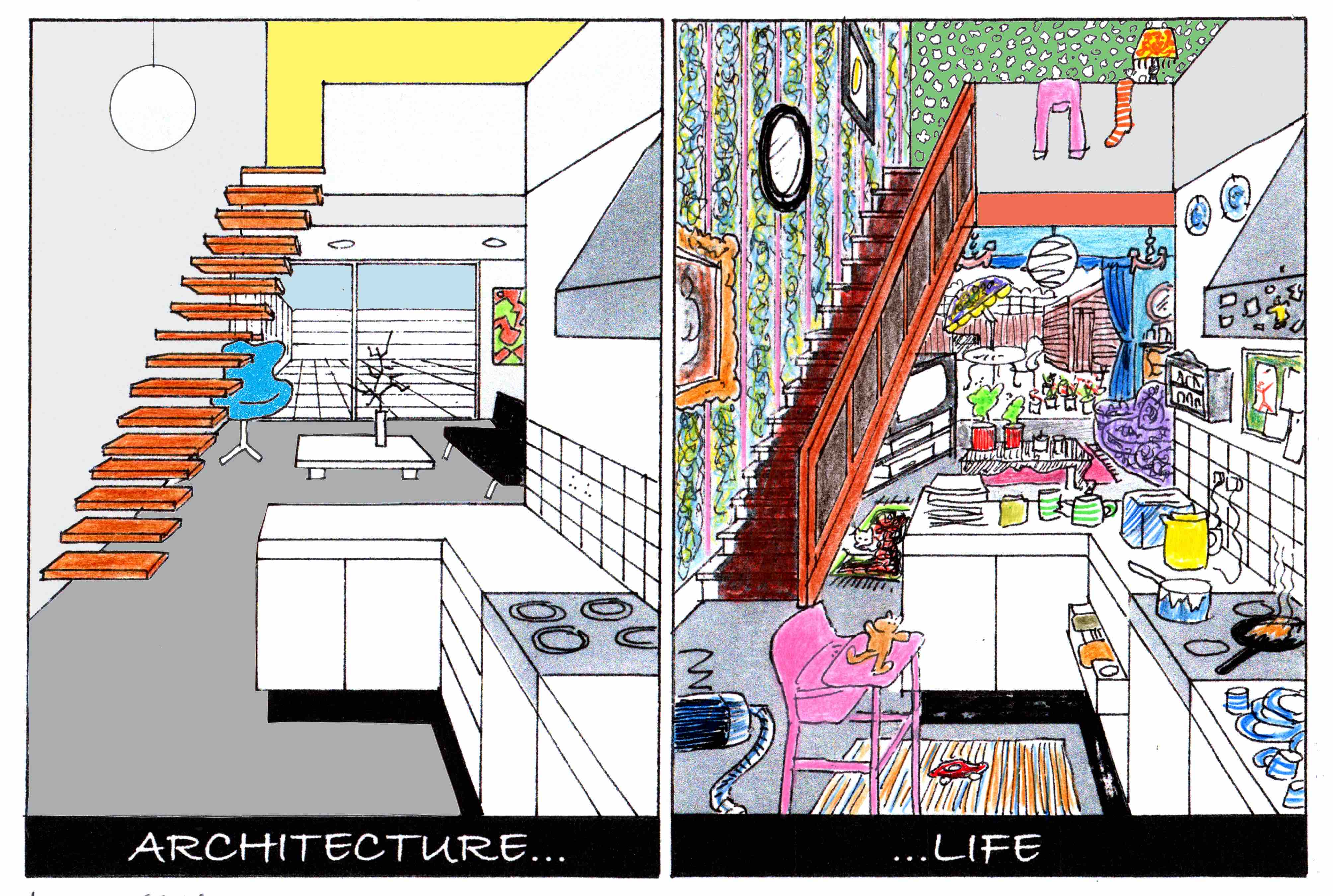

While there is always the challenge to create something truly original, having a plethora of pluralism ripe for lampooning or the reappearance of certain themes haven’t diminished. Architects, and human beings, will always fail to realise their ideals in the face of reality. There is also the infuriating insistence of people not to conform to expectations. The disparity between design assumption and hard reality will always supply a rich vein of humour, despised by architects at the time but now recognised as minor masterpieces in the observation of human behaviour.

My cartoons seemed to have an immediate impact with both positive and critical letters published in the AJ and invitations to give presentations as well as exhibitions in the UK and internationally. Whether satire changes anything is a moot point. It is said politicians welcome any mention in a cartoon and often buy the originals. Some leading architects have also bought the originals that do not always present them favourably. This may be because most cartoons today are relatively tame compared with the 18th century or early 1960s and many cartoonists display an ignorance of architects and architecture to match that of the general public or royalty. Hopefully, an architect cartoonist can bring some understanding and knowledge to his or her parodies and lampoons.

Whatever the current architectural stylistic fashion is, my cartoons have provided a strong and constant reminder to architects, clients and others about our responsibilities to the people who inhabit our buildings, our cities and our planet. I doubt whether my work has had any impact on the development of architectural design. But, in my experience, architects generally tend to feel much the same as I do. I hope my cartoons have been some sort of conduit for the profession and giving it a moral compass.

Share:

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Culture change in the UK construction industry: an anthropological perspective

I Tellam

Are people willing to share living space? Household preferences in Finland

E Ruokamo, E Kylkilahti, M Lettenmeier & A Toppinen

Towards urban LCA: examining densification alternatives for a residential neighbourhood

M Moisio, E Salmio, T Kaasalainen, S Huuhka, A Räsänen, J Lahdensivu, M Leppänen & P Kuula

A population-level framework to estimate unequal exposure to indoor heat and air pollution

R Cole, C H Simpson, L Ferguson, P Symonds, J Taylor, C Heaviside, P Murage, H L Macintyre, S Hajat, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Finnish glazed balconies: residents’ experience, wellbeing and use

L Jegard, R Castaño-Rosa, S Kilpeläinen & S Pelsmakers

Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis

C C Nwagwu, S Akin & E G Hertwich

Mapping municipal land policies: applications of flexible zoning for densification

V Götze, J-D Gerber & M Jehling

Energy sufficiency and recognition justice: a study of household consumption

A Guilbert

Linking housing, socio-demographic, environmental and mental health data at scale

P Symonds, C H Simpson, G Petrou, L Ferguson, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Measuring health inequities due to housing characteristics

K Govertsen & M Kane

Provide or prevent? Exploring sufficiency imaginaries within Danish systems of provision

L K Aagaard & T H Christensen

Imagining sufficiency through collective changes as satisfiers

O Moynat & M Sahakian

US urban land-use reform: a strategy for energy sufficiency

Z M Subin, J Lombardi, R Muralidharan, J Korn, J Malik, T Pullen, M Wei & T Hong

Mapping supply chains for energy retrofit

F Wade & Y Han

Operationalising building-related energy sufficiency measures in SMEs

I Fouiteh, J D Cabrera Santelices, A Susini & M K Patel

Promoting neighbourhood sharing: infrastructures of convenience and community

A Huber, H Heinrichs & M Jaeger-Erben

New insights into thermal comfort sufficiency in dwellings

G van Moeseke, D de Grave, A Anciaux, J Sobczak & G Wallenborn

‘Rightsize’: a housing design game for spatial and energy sufficiency

P Graham, P Nourian, E Warwick & M Gath-Morad

Implementing housing policies for a sufficient lifestyle

M Bagheri, L Roth, L Siebke, C Rohde & H-J Linke

The jobs of climate adaptation

T Denham, L Rickards & O Ajulo

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Life-cycle GHG emissions of standard houses in Thailand

B Viriyaroj, M Kuittinen & S H Gheewala

IAQ and environmental health literacy: lived experiences of vulnerable people

C Smith, A Drinkwater, M Modlich, D van der Horst & R Doherty

Living smaller: acceptance, effects and structural factors in the EU

M Lehner, J L Richter, H Kreinin, P Mamut, E Vadovics, J Henman, O Mont & D Fuchs

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Building energy use in COVID-19 lockdowns: did much change?

F Hollick, D Humphrey, T Oreszczyn, C Elwell & G Huebner

Evaluating past and future building operational emissions: improved method

S Huuhka, M Moisio & M Arnould

Normative future visioning: a critical pedagogy for transformative adaptation

T Comelli, M Pelling, M Hope, J Ensor, M E Filippi, E Y Menteşe & J McCloskey

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Systems Thinking is Needed to Achieve Sustainable Cities

As city populations grow, a critical current and future challenge for urban researchers is to provide compelling evidence of the medium and long-term co-benefits of quality, low-carbon affordable housing and compact urban design. Philippa Howden-Chapman (University of Otago) and Ralph Chapman (Victoria University of Wellington) explain why systems-based, transition-oriented research on housing and associated systemic benefits is needed now more than ever.

Unmaking Cities Can Catalyse Sustainable Transformations

Andrew Karvonen (Lund University) explains why innovation has limitations for achieving systemic change. What is also needed is a process of unmaking (i.e. phasing out existing harmful technologies, processes and practices) whilst ensuring inequalities, vulnerabilities and economic hazards are avoided. Researchers have an important role to identify what needs dismantling, identify advantageous and negative impacts and work with stakeholders and local governments.