www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/architectural-education.html

Accelerating Change in Architectural Education

Firm and rapid action by accreditation bodies and regulators is needed to make architectural education fit for purpose.

Sofie Pelsmakers (Tampere University) and Fionn Stevenson (University of Sheffield) respond to the B&C special issue 'EDUCATION & TRAINING: MAINSTREAMING ZERO CARBON'. They argue that a mandatory set of educational standards

from accreditation bodies is the key to creating the abilities, competences and values that a carbon neutral society needs.

Why

Given that 36% of the EU's CO2 emissions are associated with the built environment, it is clear that a carbon neutral society cannot be achieved without also tackling the significant emissions from building construction and operation (European Commission, 2019). In the built environment this means significant and rapid reductions in energy demand in buildings (new and retrofit), in the construction processes and in the embodied carbon in materials, different energy sources and different energy practices.1 To achieve this, building industry actors need to be upskilled and a rapid transition in built environment education needs to take place to support this urgent societal transition. This Buildings & Cities special issue, guest edited by Fionn Stevenson and Alison Kwok examines built environment education for professional and vocational workers. This commentary considers architectural education because it is lagging behind vocational training in meeting these challenges (Stevenson and Kwok, 2020).

Lock-in

In the EU and UK, the professional recognition of architecture qualifications has been prescribed by the EU directive 2013/55/EU (Official Journal of the European Union, 2013). While it sets out minimum criteria, it is generic and unambitious. Nor does it reflect the carbon neutral goals set by the EU and the UK. These minimum educational criteria apply in most other countries' education degree prescriptions and have been adopted by most schools of architecture, leading to architecture graduates not equipped to respond to the climate crisis. Although these minimum criteria can be boldly exceeded, this is rarely witnessed in academe. This situation is nothing new for those who have been at the coalface of integrating climate change in education (Architecture Education Declares, 2019).

Each year of delay that fails to provide graduates with the abilities, competences and values that a carbon neutral society needs, is another 'lock in' of an out-of-date skillset, leading to more business as usual projects being developed unless significant CPD training is provided after graduation.2 Regardless of what the directive's minimum criteria are, it is simply irresponsible that professional bodies are taking so long to respond to the urgent need for educational reform. Without leadership, no systemic shift will occur with educational criteria and standards that are not fit for purpose or if they are voluntary.

The reliance on the voluntary approach to create a fit for purpose curriculum is problematic. It creates a huge discrepancy in architects between the many who graduate with no climate literacy skills and the few with climate readiness competencies. At best, this risks reputational damage to the professions, and irrelevance at worst. Climate competencies are no longer optional, yet it is a matter of chance for students whether or not they have a teacher with the knowledge and passion to voluntarily deliver these.

The editorial (Stevenson and Kwok, 2020) describes:

"Policy levers and incentives for upskilling and transitioning built-environment education can be enacted at many different levels through codes and regulations, licensing, accreditation for programmes, professional organisations, and curricular innovation around climate change mitigation, sustainability and environmental responsibility."

Without all of the former, teachers are left to innovate, but no obligation is placed on educational institutions related to exceed minimum mandatory competencies. This approach has been proven not to work, because little or no resources are allocated, as institutions currently have no incentive or obligation to deliver beyond the stated minimum requirements.

Only a reform

of accreditation bodies' educational criteria

will ensure change. All architecture schools would have no choice but to

dedicate resources and deliver the stipulated educational outcomes. Without higher mandatory criteria, the

delivery of carbon and climate change literacies will remain piecemeal. Most of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) recent 2030

Sustainable Outcomes criteria and building standards' targets (RIBA, 2019) are

already required today in Nordic countries (some of the architecture schools in

this region are also RIBA accredited). This shows that the profession and its

regulators can - and must - aim higher. Looking at what exemplars have achieved

elsewhere is a good thing.

Systemic change requires cultural change

To achieve lasting change, a culture change is needed in both the professional institutions and in higher education itself. Architecture is often still taught as it was decades ago, with little content or pedagogical renewal to engage with issues such as building performance, social and organizational value, occupant agency and potential adaptation in a changing climate. The urgency and complexity of responding to the climate crisis requires a true collaborative effort between different professions, in practice and also in education. Stevenson and Kwok (2020) raise a broader question about collaborative working and its implications for higher education. They recommend an education to create 'archineers': 'T-shaped' professionals who embrace aesthetics, climate literacy, expert knowledge in a particular area, but also the ability to truly collaborate with other disciplines. The future generation of architects require an education that provides the knowledge, critical attitude and values to know what questions to ask, which experts to invite around the table, how to collaborate effectively and how to navigate the best solutions each time.

Surprisingly, there is no mandatory CPD for educators in terms of learning how to teach climate literacy to a proven competency level. The real bottleneck is the teachers who educate the future generation. But how can the next generation be taught these things when many teachers do not themselves hold the very competences they are supposed to teach? (See commentaries by Marco, 2020 and Samuel and Farrelly 2020.)

The teaching of sustainability requires

adapted pedagogies and dedicated learning activities that are embedded in

design studio to ensure new knowledge is applied, tested and integrated in

design projects (Donovan, 2017, Altomonte, 2009). This requires resources and

essential teacher training, yet is usually considered an 'add on' to

architecture education. One positive example (amongst others) is the EU funded

ARCH4CHANGE international education project. This recognises climate literacy education is

about what to teach as well as how to teach it. It aims to provide

competences by creating a free climate emergency digital curriculum for

students and also provides an innovative training toolkit with pedagogical

methods for teachers (European Commission, 2020). The teacher

training toolkit will explicitly provide - based

on best practice, and tested pedagogies - not only subject matter to students

and teachers, but also a route through different teaching methods to upskill

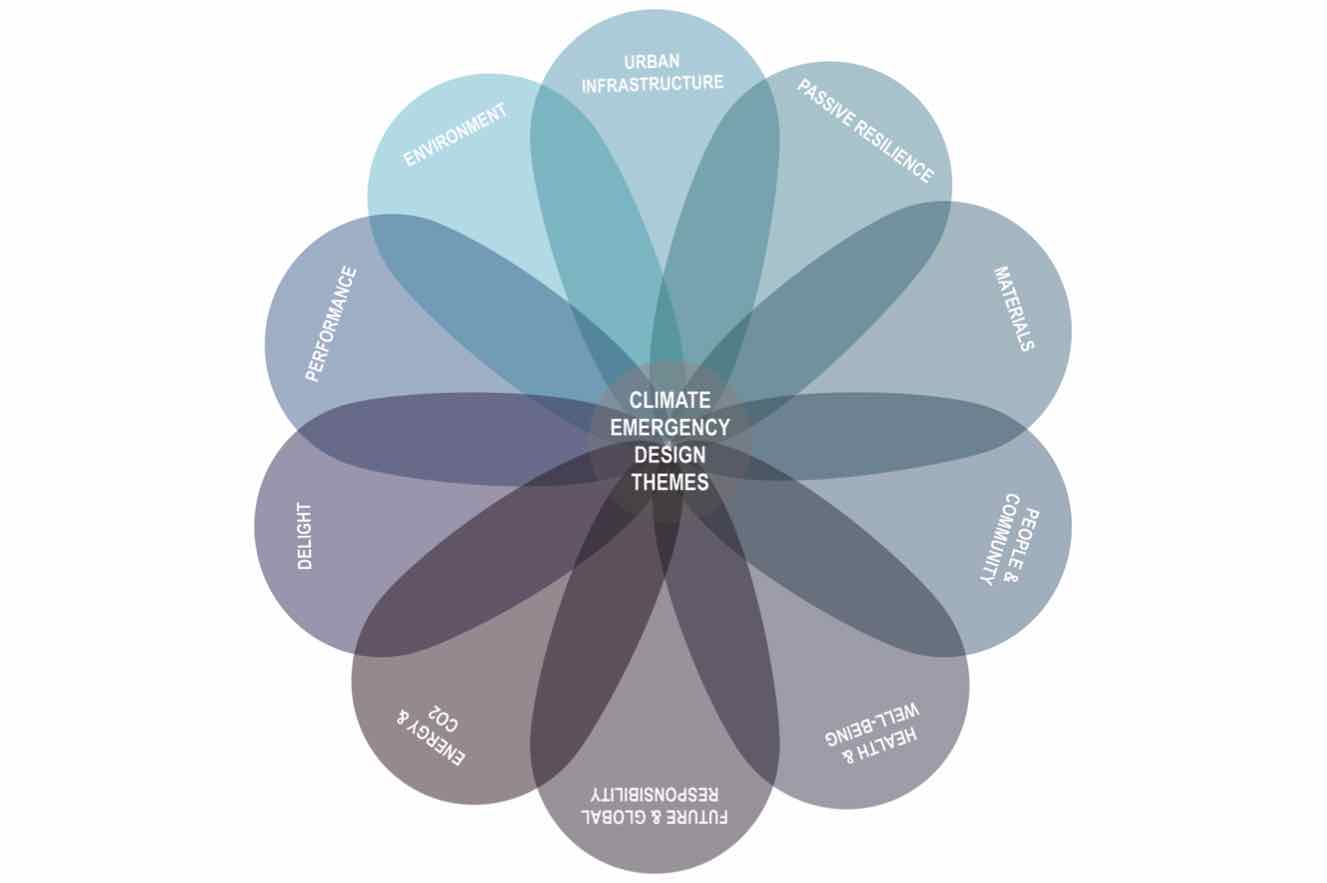

teachers. The ARCH4CHANGE curriculum centres around 10 key sustainability

themes - see Figure 1. All of these themes must be met to move towards restorative

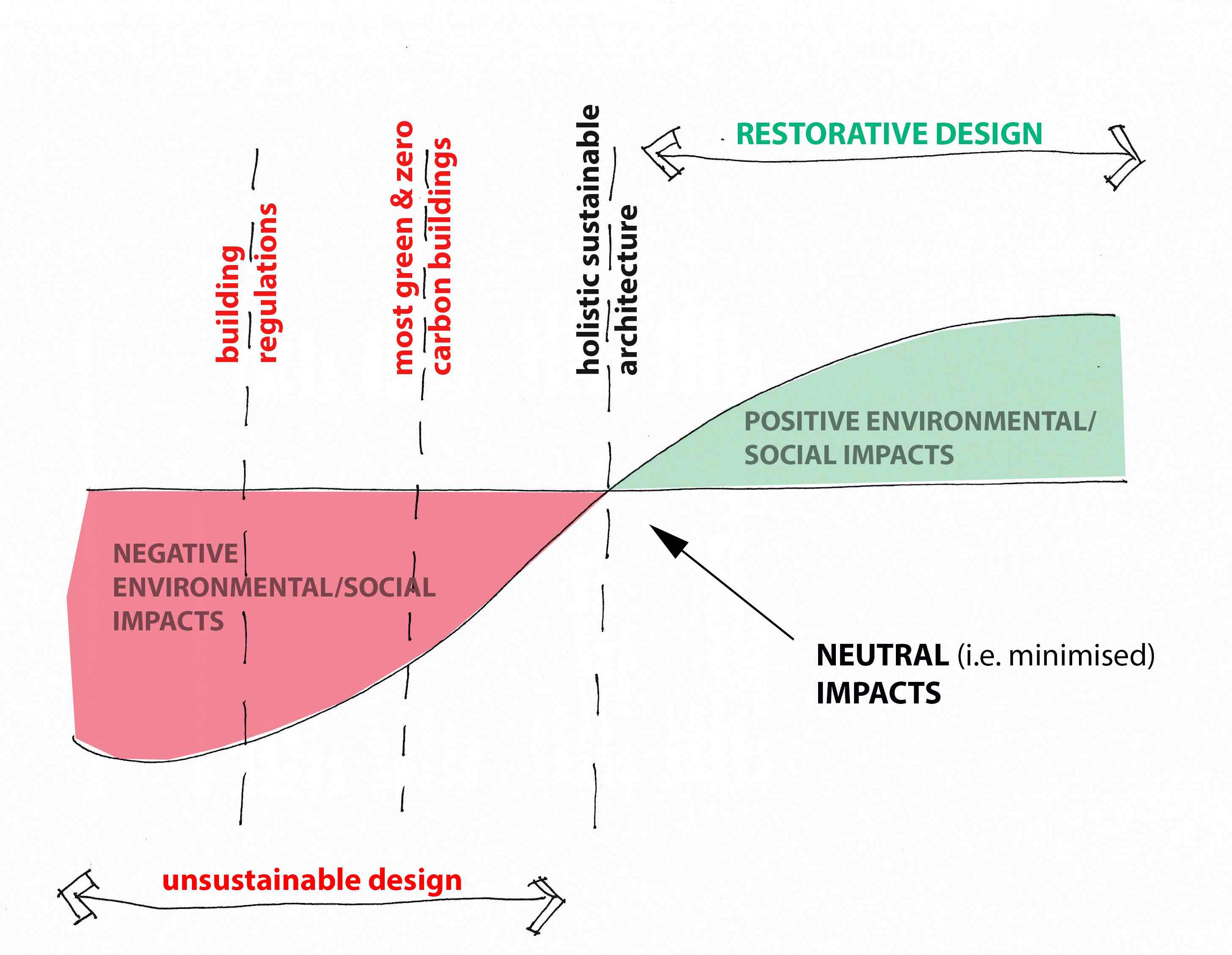

design - see Figure 2.

A broad curriculum

The comprehensive nature of the curriculum is crucial and relates to a question in the editorial whether "educators should prioritise energy-related zero-carbon design targets within wider sustainability issues as set out in the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?" (Stevenson and Kwok, 2020). Built environment curricula should prioritise energy and carbon issues, but this cannot be at the expense of other sustainability aspects. A zero-carbon home needs to fulfil other criteria e.g. affordability, accessibility, healthy environment and adaptability. Indeed, all of these aspects must go hand in hand. As Figure 2 shows, often green building standards still have negative environmental and social impacts. Higher standards in all aspects of sustainability are needed to create restorative designs.

Wake up: call for action

The Buildings & Cities educational special issue provides several positive examples of innovative pedagogies. It is an urgent call for action for the professional organisations to be ambitious and ensure those entering the built environment professions are equipped with the right knowledge, skills, character and ways of working to be able to fulfil our role in community and society. This commentary argues that a mandatory set of educational standards from accreditation bodies is the key to creating this change. Deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are needed by 2030 (IPCC, 2018) making it essential to have a profession capable of meeting this and other climate- related goals.

If education is not shifted in the right direction, then we risk locking-in another generation of professionals ill-equipped to deal with the enormous challenges we face as a society. Each year that graduates are not equipped with the skills needed, is a lost year.

References

Altomonte, S. (2009). Environmental education for sustainable architecture. Review of European Studies, 1(2), 12-21.

Architecture Education Declares. (2019).

https://www.architectureeducationdeclares.com/

ARCH4CHANGE. https://www.arch4change.com/

European Commission. (2019). Sustainable buildings for Europe's climate-neutral future. https://ec.europa.eu/easme/en/news/sustainable-buildings-europe-s-climate-neutral-future

European Commission. (2020). Digital climate change curriculum for architectural education: methods towards carbon neutrality. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2020-1-FI01-KA203-066628

Donovan, E. (2017). Sustainable architecture theory in education: how architecture students engage and process knowledge of sustainable architecture. In W.L. Fino (ed) Implementing Sustainability in the Curriculum of Universities: Approaches, Methods and Projects. Cham: Springer.

IPCC. (2018). Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)] https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/SR15_SPM_version_report_LR.pdf

Living Building Challenge. (2020). Living Building Challenge 4.0 Basics. https://living-future.org/lbc/basics4-0/

Official Journal of the European Union. (2013). Directive 2013/55/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 amending Directive 2005/36/EC on the recognition of professional qualifications and Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012 on administrative cooperation through the Internal Market Information System ('the IMI Regulation'). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:354:0132:0170:en:PDF

Pelsmakers, S. Donovan, L, Kozminska, K, Hoggard, A. (forthcoming 2022). Designing for the Climate Emergency: A Guide for Architecture Students. London: RIBA Publishing.

RIBA (2019). 2030 Sustainable Outcomes Guide. https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/sustainable-outcomes-guide

Stevenson, F. and Kwok, A. (2020). Mainstreaming zero carbon: lessons for built-environment education and training. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 687-696. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.84

Notes

1. Although the energy supply may be decarbonised over the next 30+ years, the urgency to reduce GHG emissions means that both energy demand and decarbonisation are necessary.

2. A reliance on continuing professional development (CPD) also shifts educational institutions' responsibility to other institutions to deliver what are ultimately core competencies.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.