www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/beyond-theory-climate-justice-practice.html

Beyond Theory: Climate Justice in Practice

What role does the built environment have in addressing climate injustices?

This community-led initiative provides a practical approach to addressing climate injustices, specifically those experienced by Black and brown communities and low-income residents in Portland, Oregon. Rev. E.D. Mondainé and Mandy Lee present a pioneering approach that embraces both climate (mitigation and adaptation) and inequality issues to improve community resilience and wellbeing. A climate justice approach is better than attempting to solve one issue at a time.

A background of injustice

Communities around the world are already grappling with the impacts of the climate crisis. In Portland, Oregon, residents experienced a drastic example of this crisis in August 2018, when major wildfires from increasingly warmer and drier summer conditions resulted in the worst air quality in the world for their neighborhoods (OCCRI 2018). Despite the global need for unprecedented, "rapid and far-reaching transitions" in all aspects of society, the US has entered a period of political denial and obstruction in many areas (IPCC 2018; Wilson 2019; Davenport and Landler 2019).

Simultaneously, a crisis of economic inequality exists. Despite a record-setting 10-year economic expansion, the top 30% of wealthy Americans hold a greater share of the country's wealth than before the Great Recession of 2007-2009 (BGFR 2019; Rugaber 2019). Meanwhile, middle-class and poor Americans in the bottom 70% have yet to see their wealth recover to pre-recession levels. In Oregon, the income gap between the richest residents and typical Oregonians reached a historic peak in 2016, leading the Oregon Center for Public Policy to call inequality "…the greatest challenge facing Oregon today" (Hauser and Ordonez, 2019).

Taken together, the impacts of climate change and inequality create an enormous threat to community well-being, and they disproportionately burden people of color and low-income people, who have far more vulnerability and far less capacity to recover from these crises (UW Climate Impacts Group et al. 2018).

Part of a long history of economic and environmental racism, Portland's legacy of historic redlining and housing discrimination restricted African Americans to a single neighborhood in central Portland in 1919 called Albina (Semuels 2016; Stroud 1999). Since then, Albina and other predominantly non-white neighborhoods have been subject to disinvestment and urban renewal projects that razed the homes of hundreds of families at a time. Characterized by some as "two Portlands," communities east of the Willamette River have long been disregarded. In addition, a new divide has emerged between Portland's inner and outer eastside, defined by the unofficial former city limit at 82nd Avenue.

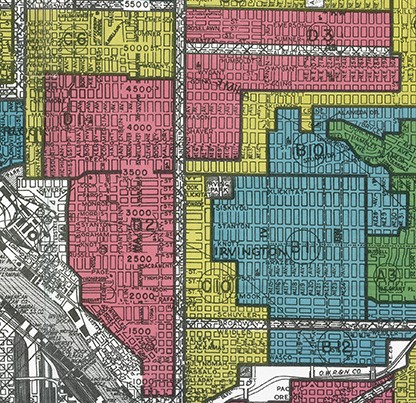

Figure 1. From the 1920s to 1940s, federal maps divided U.S. cities into red ("hazardous"), yellow ("definitely declining"), blue ("still desirable") and green ("good"), based in part on what associated records called "infiltration" of "subversive races." Pictured in red is the Albina District in Portland. Adapted from Mapping Inequality , by R. K. Nelson et al., 2020: University of Richmond.

Since the 1990s, an influx of white residents and investment-driven gentrification has created a displacement crisis. In just ten years (from 2000-2010), 10,000 African American residents were displaced from northeast Portland, and the citywide Black population has dipped to less than 6% (Sevcenko 2018). Black families in Portland lag behind white families and Black families nationally for employment, health outcomes, income, and homeownership. Black and Latinx residents are still charged higher rents, deposits, or additional fees than their white counterparts. In 2017, research revealed that there were no neighborhoods affordable to rent or purchase a home for the average Black, Latinx, Native American, and single-mother household in Portland (IPS, 2019).

Another example of modern forces of displacement is a 2018 city ordinance requiring owners of unreinforced masonry buildings to post a placard on main entrances reading: "This is an unreinforced masonry building. Unreinforced masonry buildings may be unsafe in the event of a major earthquake" (BDS 2019). In addition to procedural violations of the federal Constitution, building owners and community members successfully rallied against an anticipated redlining effect from the placards that would lead to lost value, complications with tenants, significant barriers to financing and selling, increased demolition rates, and displacement and gentrification of small businesses, churches, and other institutions that are "cornerstones of community" (Acosta 2019; Bosco-Milligan Foundation 1997; Portland NAACP 2019).

Coalition for climate justice

To address climate justice, a coalition in Portland emerged with core leadership from African-American, Native American, Latinx, and Asian-Pacific Islander communities. They shared "…a fundamental commitment to Portlanders who are most impacted by climate change but have been excluded from the emerging low-carbon economy" (PCEF 2019). These "frontline" communities are those directly affected by climate change and inequality at higher rates than those with more power in society. Starting with a steering committee of six frontline, community-facing organizations, as well as five environmental partners, the coalition has grown to more than 200 organizations and individuals (PCEF 2019).

The core coalition organizers established shared values very early in the process. Members of frontline communities held primary leadership, strategy, and public speaking roles, while predominantly white environmental organizations provided capacity and resources in planning and campaigning, largely through funding and pro-bono services. Unlike the approach of many environmental groups and political campaigns, the coalition also abided by informal norms for conduct in meetings and collaboration. For example, the decision-making bodies strove for consensus; however, if consensus was not reached, the group deferred to frontline leadership.

An unexpected outcome of the campaign was the endorsement of building trades unions and a productive partnership with environmentalists for the first time in recent memory. Together, these groups identified a shared opportunity to resolve the industry's challenges in recruiting, training, and retaining enough skilled workers. The PCEF opened the possibility for environmental organizations and climate justice groups to potentially have open dialogue with building trades unions about contentious areas, such as their opposition to a new liquefied natural gas terminal proposed along the Oregon coast.

New principles for policy and practice

The coalition argued that the City needed to urgently mobilize funding to accelerate greenhouse gas reductions in marginalized, frontline communities. To meet the need for more skilled workers to implement climate initiatives, the coalition pointed to underrepresented and historically disadvantaged groups as an "enormous untapped resource" (City of Portland 2019).

Exercising their right to enact laws by citizen initiative, the coalition proposed a ballot measure (Measure 26-201) to require approximately 120 large retailers (with annual revenues exceeding $1 billion nationally and $500,000 in Portland) to pay a surcharge of 1% on gross revenues from retail sales in Portland, excluding basic groceries, medicines, and health care services. The approach of a ballot initiative was chosen over a legislative campaign through the city council in order to build the political power of residents, as well as to avoid counter-initiatives by the fossil fuel industry and large corporations. In the November 2018 general election in which the ballot measure passed, voter turnout reached a historic high of 74% (PCA 2018).Allocated to the Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund (PCEF), the money raised will support qualified non-profit organizations (alone or in partnership with other entities) implementing the renewable energy, energy efficiency, clean energy workforce development, regenerative agriculture, and green infrastructure programs, prioritizing the following:

Economically disadvantaged and traditionally underrepresented workers in the skilled workforce (including people of color, women, persons with disabilities, and chronically un-employed)

- Rent stability

- Low-income residents and communities of color

- Entry into union registered apprentice trades

- Community-based and decentralized energy strategies

- US-made renewable energy products

- Co-benefits for economic, social, and environmental justice

- Organizations with a proven record of working with disadvantaged community members

Together, these initiatives will build and strengthen new forms of economic and social resilience within communities that have traditionally been disinvested. For example, community benefits from funded projects might include solar panels and energy efficiency upgrades on multifamily housing, new workforce training programs in clean energy manufacturing and installation, shared food gardens, and increased tree canopy in heavily concreted neighborhoods. This will allow individuals, families, and neighborhoods to reduce their energy cost burden, increase access to family-sustaining wages in high-quality jobs, decrease pollution from fossil fuel energy sources, expand access to fresh and affordable local foods, reduce health stressors and the impacts of extreme weather events, and generally free up resources and time to sustain and enhance wellbeing.

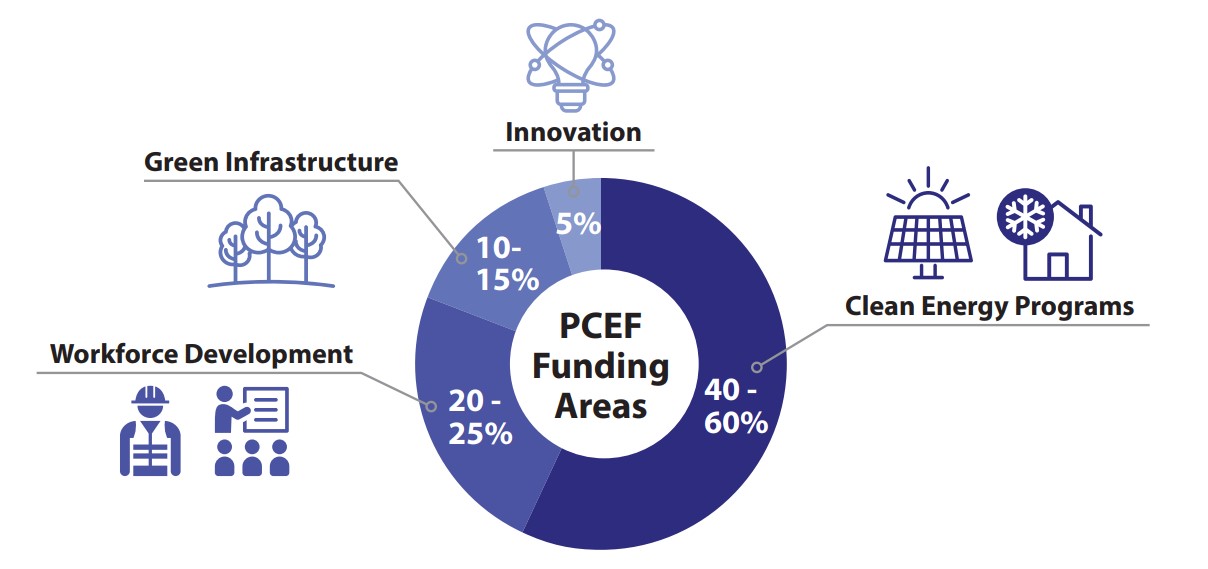

Figure 2. The Portland

Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund finances

programs according to various priorities. Image: Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund.

Projects receiving funding will also agree to a Workforce and Contactor Equity Agreement developed by the Committee and meet family wage standards.

The Fund is administered by the Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Committee, made up of nine experts and community members who must reflect the racial, ethnic and economic diversity of the City of Portland, including at least two residents living east of 82nd Avenue.

The Fund passed via local ballot measure in November 2018 with 65% of voters in support. It is anticipated to fully launch in 2020 with $54-71 million in new revenue.

Figure 3. Projects funded by PCEF will prioritize creating family-wage jobs, healthier homes and reduced utility costs for the communities most impacted by climate change and inequality. Image: Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund.

Implementation, evaluation and replication

It is too soon to evaluate the distribution and impacts of projects funded by the PCEF for equity and climate adaptation. However, it is possible to begin observing outcomes for representation in decision-making and preservation of frontline leadership without political interference.

In recognition of the coalition's leadership and ongoing advocacy, the City is collaborating to create a new standard for all city processes and relationships with the community. The PCEF coalition has publicly praised the City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability for bringing the necessary skills and expertise, commitment to the program's goals and values, and racial and geographic diversity (BPS 2019b).

Other examples of transformation include the placement of job announcements for the program in the city's oldest African American newspaper, translating the application for committee membership into 11 languages, and ensuring financial accommodations for committee members requiring childcare and transportation reimbursement. In another striking example of transformation, one of the first coalition members from the Portland Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Jo Ann Hardesty, became the first woman of color elected to the Portland City Council in January 2019. A key piece of her platform was the PCEF.

When considering how to replicate and improve upon this policy, the success of establishing the PCEF must be understood within the political, social, economic, and historical context of Portland. As a city with a liberal Democratic majority, residents have proven to be very supportive of action on climate change, investment as a means to take climate action, and taxation as a funding source.

While the policy language of the ballot measure itself is highly replicable, other cities and communities would need to evaluate the feasibility of taxation, targeting large corporations, proposing the policy via a ballot measure, the breakdown of funding allocation among different priority areas, definition of frontline communities in a local context, and narrative framing. Other options for funding mechanisms include: a flat tax, business license tax, property tax, sales tax, visitor tax on hotels and rental cars, income tax on the wealthiest, fine for failing to adhere to climate standards regulating emissions, and/or seeking funds from the county, state, or federal government

The policy could deepen its commitment to the health and wellbeing of future generations by prioritizing youth in workforce development and addressing gentrification and displacement more broadly. In addition to requiring that efficiency and renewable energy projects ensure rent stability, a requirement or a portion of funds could be dedicated to long-term wealth creation through programs for homeownership.

Lastly, where possible, a greater focus on investments for public transit systems and affordability should be assessed. Despite the fact that transportation is responsible for 41% of energy-related emissions in Multnomah County, OR, and is the only sector to see increasing emissions between 2000 and 2017, the state regulatory context inhibited the PCEF coalition from incorporating this issue into the scope of the Fund (BPS 2019a).

A model of climate justice in practice

A review of policy principles underpinning the PCEF indicate that it is an exemplary embodiment of climate justice in terms of distributional, process, and intergenerational equity (King County 2016). The PCEF radically shifted possibilities for climate justice in the context of the built environment for Portland's frontline communities. Nonetheless, it is critical to note that the mobilization for the PCEF ballot measure campaign would have been unnecessary if the city government had already had a meaningful commitment and process for working with and empowering frontline communities in budgeting, sustainability, and planning.

The PCEF dramatically expands the resources available to residents most impacted by climate change and inequality (and decreases competition for funding by organizations serving these residents), while maintaining community leadership and ownership of the program. Thanks to three years of deeply collaborative organizing, billions of dollars will be invested to advance energy efficiency, renewable energy, green infrastructure, and a just transition to clean jobs for frontline communities in coming decades. The PCEF takes a comprehensive and visionary approach to climate justice that inspires positive advocacy rather than defensive protest.

For additional insights from the organizing

coalition, we encourage readers to explore: A Template for Change: The Portland

Clean Energy Fund as a Local Model for a Green New Deal.

Competing interests

EM is a member of the steering committee of the PCEF coalition on behalf of Portland NAACP, which is on a voluntary basis. ML is associated with Portland NAACP as a national NAACP staff member providing research and resources to state and local NAACP units across the country.

References

Acosta, John. (2019). Case No. 3:18-cv-02194-AC Opinion and Order. United States District Court District of Oregon Portland Division. Retrieved September 3, 2019, from email communications.

BDS - Bureau of Development Services, City of Portland. (2019). Unreinforced Masonry (URM) Building Information. Retrieved from https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bds/70766

BGFR - Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2019). Accessible Version: Is the Middle Class Within Reach for Middle-Income Families? Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20190509a1.htm.

Bosco-Milligan Foundation Architectural Heritage Center. (1997). Cornerstones of Community: Buildings of Portland's African American History. Retrieved from https://www.oregon.gov/oprd/HCD/OHC/docs/multnomah_portland_BuildingsOfPDXAfricanAmericanHistory_REVISED.pdf

BPS - Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, City of Portland. (2019a). Climate Action. Retrieved from https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/64076

BPS - Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, City of Portland. (2019b). Media Release: Portland City Council votes to appoint first five members of the Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits Fund Committee. Retrieved from https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/742677

City of Portland. (2019). City Code & Charter Title 7 Business Licenses Chapter 7.07 Portland Clean Energy Community Benefits. Retrieved from https://www.portlandoregon.gov/citycode/78811

Davenport, Coral, and Mark Landler. (2019, 27 May). Trump Administration Hardens Its Attack on Climate Science. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/27/us/politics/trump-climate-science.html

Hauser, Daniel, and Juan Carlos Ordonez. (2019). Oregon's Ultra-Rich Continue to Pull Away. Oregon Center for Public Policy. Retrieved from https://www.ocpp.org/2019/03/06/oregon-ultra-rich-income-inequality/.

IPCC - International Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/.

IPS - Institute for Policy Studies. (2019). Wealth Inequality in the United States. Retrieved from https://inequality.org/facts/wealth-inequality/.

King County. (2016). 2015 Equity Impact Review Process Overview. Retrieved from https://www.kingcounty.gov/~/media/elected/executive/equity-social-justice/2016/The_Equity_Impact_Review_checklist_Mar2016.ashx?la=en

OCCRI - Oregon Climate Change Research Institute. (2019). Fourth Oregon Climate Assessment Report State of climate science: 2019 Summary. Retrieved from http://www.occri.net/media/1092/execsummaryocar4.pdf.

OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon. (2019). HB 2020: Oregon's Carbon Trading Bill. Retrieved from http://www.opalpdx.org/2019/04/hb2020/

PCA - Portland City Auditor Elections Division. (2018). Nov. 6, 2018 General Election - City of Portland Results Summary. Retrieved from https://www.portlandoregon.gov/auditor/article/705814

PCEF -Portland Clean Energy Fund. (2019). About. Retrieved from https://portlandcleanenergyfund.org/about

Portland NAACP. (2019). Unreinforced Masonry Coalition. Retrieved September 3, 2019, from email communications.

Rugaber, Christopher. (2019). Why wealth gap has grown despite record-long economic growth. AP News. Retrieved from https://www.apnews.com/df1ca4016d27405791c10eb5772c06a4.

Semuels, Alana. (2016). The Racist History of Portland, the Whitest City in America. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/07/racist-history-portland/492035/

Sevcenko, Melanie. (2018). Un-gentrifying Portland: scheme helps displaced residents come home. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/mar/01/portland-anti-gentrification-housing-scheme-right-return

Stroud, Ellen. (1999). Troubled Waters in Ecotopia: Environmental Racism in Portland, Oregon. Radical History Review, 74, 65-95. Retrieved from http://web.mit.edu/people/spirn/Public/Granite%20Garden%20Research/Urban%20Environmental%20History/Stroud%201999%20Environmental%20Racism%20Portland.pdf

UW Climate Impacts Group, UW Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, Front and Centered, and Urban@UW. (2018). An Unfair Share: Exploring the disproportionate risks from climate change facing Washington state communities. Retrieved from https://cig.uw.edu/our-work/applied-research/an-unfair-share-report/

Wilson, Jason. (2019). How Republicans killed Oregon's climate crisis bill - by fleeing the state. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jun/28/how-republican-senators-killed-oregons-climate-crisis-bill

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.