www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/christopher-alexander.html

Christopher Alexander's Pursuit of Living Structure in Cities

The Cartesian mechanistic worldview is essentially unable to create living cities. Lessons about connections can help to make cities more sustainable.

Bin Jiang (University of Gävle) reflects on Christopher Alexander's (1936-2022) pursuit of living environments with a recurring notion of far more small substructures than large substructures.

[Living structure] is a fundamental view of the world. It says that when you build a thing you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent, and more whole; and the thing which you make takes its place in the web of nature, as you make it.

(Alexander et al. 1977)

A Pattern Language (Alexander et al. 1977) triggered, among other things, object-oriented programming, and the Wikipedia framework. Christopher Alexander's fundamental view of the world states that space, both inside and outside our body, is neither lifeless nor neutral, but a living structure capable of being more living or less living. It is also referred to as the third view of space (Jiang & Huang 2021, Jiang 2022). This is in contrast to Newtonian absolute space and Leibnizian relational space, both of which are framed under the Cartesian mechanistic worldview. A living structure consists of far more small substructures than large ones across all scales (or hierarchical levels), but substructures on each of the scales (or hierarchical levels) are more or less similar in size (Figure 1). London has six hierarchical levels, but Manhattan has only three. In The Nature of Order, Alexander (2002-2005) used the term center to refer to what I refer to here as substructure.

Alexander's (2002-2005) understanding of space was substantially inspired by the organismic worldview, first conceived by the British philosopher Alfred Whitehead (1929), that extends the Cartesian mechanistic worldview to include human beings as part of the world picture. Thus, humans are inherently connected to things in our surroundings, just as things themselves are internally connected rather than externally connected. The same worldview had been advocated by many writers including the quantum physicist David Bohm (1980).

In Alexander's view, a thing is not an isolated entity, but part of an interconnected whole. To learn how 'good' that thing is, it must be assessed holistically with respect to the context of that thing. For example, a room is a substructure of the building, which is a substructure of the street, which is a substructure of the city, which is a substructure of the country towards the entire Earth or the cosmos. On the other hand, that same room also contains far more small substructures than large ones at different levels of scale (or hierarchy). For example, a wall with a painting may further contain far more 'smalls' than 'larges'. Therefore, the goodness of that room depends on its adjacent rooms and things, on the smaller things within that room, and on the larger thing (or the building) that contains that room. It is essentially a recursive definition about the goodness of a space.

This thinking also applies to the way that Google ranks the relevance or importance of a webpage. A webpage is not isolated, but part of the huge web graph consisting of billions and billions of interconnected webpages. For any given search, there are always far more less-relevant webpages than more-relevant ones, and the most relevant ones appear in the first page of the searched results. In other words, the relevance or importance of a webpage depends on those in-linked webpages. Through the web graph and built on the recursive definition that important pages are those to which many important pages point, the PageRank algorithm (Page and Brin 1998) can efficiently and effectively calculate the ranking score.

In the end, these seemingly subjective terms - relevance, goodness, coherence, and wholeness - are in fact objective or act as a structure in nature. Alexander had this idea of the PageRank algorithm when he was working on the pattern language work (Alexander et al. 1977). Interestingly, he had the same kind of complex network (or web graph) thinking, while he was working on his earlier works (Alexander 1964, 1965). In this regard, he is a genuine pioneer of complex networks.

The relevance, 'goodness', coherence, or wholeness of a thing is a matter of fact rather than opinion or personal preference. Such an understanding is deemed to be universal and largely triggered by the underlying structural character called living structure. This shared notion of goodness or the quality without a name (Alexander 1979) should become the hard and universal standard of sustainable urban planning. Fortunately, a mathematical model of living structure or wholeness (Jiang 2015a, 2019) has been developed to address not only why a structure is beautiful, but also how beautiful the structure is. The mathematical model relies on two factors to determine the degree of livingness or goodness: (1) the number of substructures, and (2) their inherent hierarchy. The more substructures it has, the more living it is. Likewise, the higher hierarchy of the substructures it has, the more living it is. Figure 1 illustrates that the city of London is more living or more beautiful (as a plan) than Manhattan.

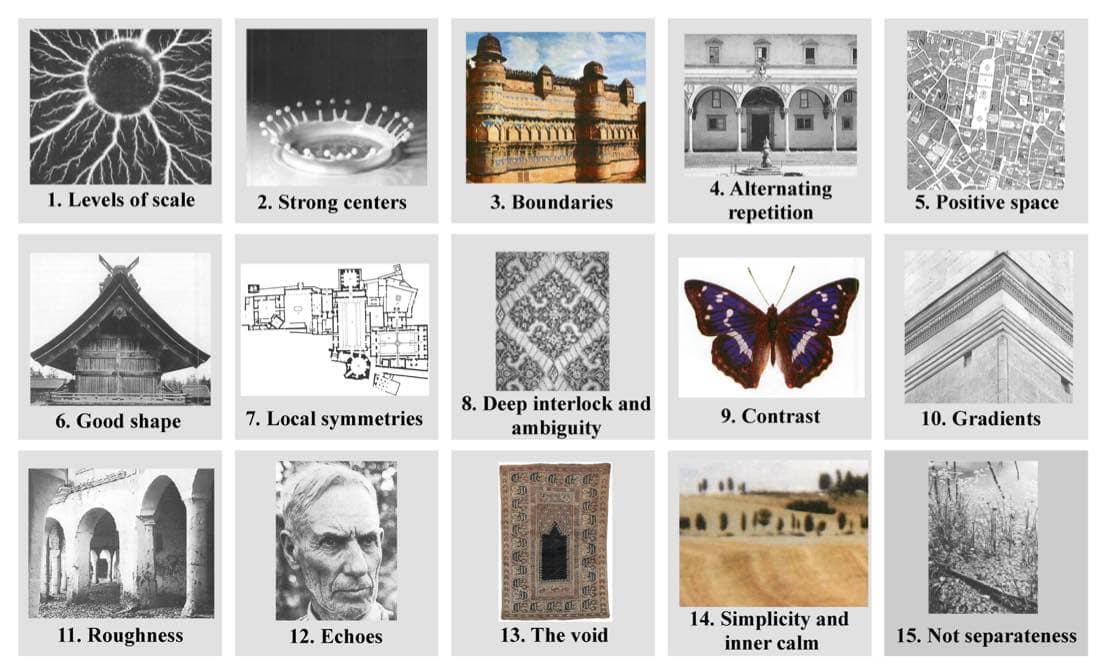

Alexander's view of space implies that sustainable urban planning is not LEGO-like assembly of prefabricated elements, but an embryo-like growth guided by two design principles - differentiation and adaptation - towards a coherent or more coherent whole. A city or community is persistently differentiated like cell division in a step-by-step fashion to generate far more small substructures than large ones, and the differentiated substructures must adapt to each other not only locally but also globally. That is required to meet the two notions or two laws of living structure: far more small substructures than large ones across all scales (the scaling law, Jiang 2015b) and more or less similar substructures on each of the scales (Tobler's law, which is commonly called the first law of geography) (Tobler 1970). These two laws underlie the 15 properties (Figure 2) that were distilled or discovered by Alexander (2002-2005) from traditional cities, buildings, and artifacts. These 15 properties exist - pervasively - not only in what humans create (e.g. buildings, cities, carpets, etc), but also in nature or naturally occurring things of various kinds.

To create a city or a building is essentially to transform that place into a more coherent entity. The transformed city or building should directly contribute to that place to become living or more living. The transformation also called wholeness-enhanced unfolding proceeds in a step-by-step fashion. Once that place is well shaped as a living structure, it tends to shape the behavior of human beings. To paraphrase Winston Churchill (1874-1965), we first shape our space to be a living structure, and afterwards our activities are shaped by it. It should be noted that this process of "shape and shaped-by" goes in a never-ending recursive manner or in a timeless way (Alexander 1979). Unfortunately, the science of the past 300 years, framed under the Cartesian mechanistic worldview, is essentially unable to create living cities, as argued by Alexander (2002-2005). It is the time for us to embrace the Whiteheadian organismic worldview in order to transform modern cities to be living or more living towards a sustainable society.

References

Alexander, C. (1964). Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Cambridge Harvard University Press.

Alexander, C. (1965). A city is not a tree. Architectural Forum, 122(1+2), 58-62.

Alexander, C. (1979). The Timeless Way of Building. New York: Oxford University Press.

Alexander, C. (2002-2005). The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe. Berkeley: Center for Environmental Structure.

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, M., Fiksdahl-King, I & Angel, S. (1977). A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the Implicate Order. London: Routledge.

Jiang, B. (2015a). Wholeness as a hierarchical graph to capture the nature of space. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 29(9), 1632-1648.

Jiang, B. (2015b). Geospatial analysis requires a different way of thinking: the problem of spatial heterogeneity. GeoJournal, 80(1), 1-13.

Jiang, B. (2019). Living structure down to earth and up to heaven: Christopher Alexander. Urban Science, 3(3), 96.

Jiang, B. (2022). A new kind of city science built on living structure and on the third view of space,. Coordinates, February issue, 16-25.

Jiang, B. & Huang, J. (2021). A new approach to detecting and designing living structure of urban environments. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 88, 1-10.

Page, L. & Brin, S. (1998). The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine, In: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on World Wide Web. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 107-117.

Tobler, W. (1970). A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Economic Geography, 46(2), 234-240.

Whitehead,

A. N. (1929). Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: The

Free Press.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Acceptability of sufficiency consumption policies by Finnish households

E Nuorivaara & S Ahvenharju

Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse

É Savoie, J P Sapinski & A-M Laroche

Cooler streets for a cycleable city: assessing policy alignment

C Tang & J Bush

Understanding the embodied carbon credentials of modern methods of construction

R O'Hegarty, A McCarthy, J O'Hagan, T Thanapornpakornsin, S Raffoul & O Kinnane

The changing typology of urban apartment buildings in Aurinkolahti

S Meriläinen & A Tervo

Embodied climate impacts in urban development: a neighbourhood case study

S Sjökvist, N Francart, M Balouktsi & H Birgisdottir

Environmental effects of urban wind energy harvesting: a review

I Tsionas, M laguno-Munitxa & A Stephan

Office environment and employee differences by company health management certification

S Arata, M Sugiuchi, T Ikaga, Y Shiraishi, T Hayashi, S Ando & S Kawakubo

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Culture change in the UK construction industry: an anthropological perspective

I Tellam

Are people willing to share living space? Household preferences in Finland

E Ruokamo, E Kylkilahti, M Lettenmeier & A Toppinen

Towards urban LCA: examining densification alternatives for a residential neighbourhood

M Moisio, E Salmio, T Kaasalainen, S Huuhka, A Räsänen, J Lahdensivu, M Leppänen & P Kuula

A population-level framework to estimate unequal exposure to indoor heat and air pollution

R Cole, C H Simpson, L Ferguson, P Symonds, J Taylor, C Heaviside, P Murage, H L Macintyre, S Hajat, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Finnish glazed balconies: residents' experience, wellbeing and use

L Jegard, R Castaño-Rosa, S Kilpeläinen & S Pelsmakers

Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis

C C Nwagwu, S Akin & E G Hertwich

Mapping municipal land policies: applications of flexible zoning for densification

V Götze, J-D Gerber & M Jehling

Energy sufficiency and recognition justice: a study of household consumption

A Guilbert

Linking housing, socio-demographic, environmental and mental health data at scale

P Symonds, C H Simpson, G Petrou, L Ferguson, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Measuring health inequities due to housing characteristics

K Govertsen & M Kane

Provide or prevent? Exploring sufficiency imaginaries within Danish systems of provision

L K Aagaard & T H Christensen

Imagining sufficiency through collective changes as satisfiers

O Moynat & M Sahakian

US urban land-use reform: a strategy for energy sufficiency

Z M Subin, J Lombardi, R Muralidharan, J Korn, J Malik, T Pullen, M Wei & T Hong

Mapping supply chains for energy retrofit

F Wade & Y Han

Operationalising building-related energy sufficiency measures in SMEs

I Fouiteh, J D Cabrera Santelices, A Susini & M K Patel

Promoting neighbourhood sharing: infrastructures of convenience and community

A Huber, H Heinrichs & M Jaeger-Erben

New insights into thermal comfort sufficiency in dwellings

G van Moeseke, D de Grave, A Anciaux, J Sobczak & G Wallenborn

'Rightsize': a housing design game for spatial and energy sufficiency

P Graham, P Nourian, E Warwick & M Gath-Morad

Implementing housing policies for a sufficient lifestyle

M Bagheri, L Roth, L Siebke, C Rohde & H-J Linke

The jobs of climate adaptation

T Denham, L Rickards & O Ajulo

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Decolonising Cities: The Role of Street Naming

During colonialisation, street names were drawn from historical and societal contexts of the colonisers. Street nomenclature deployed by colonial administrators has a role in legitimising historical narratives and decentring local languages, cultures and heritage. Buyana Kareem examines street renaming as an important element of decolonisation.

Integrating Nature into Cities

Increasing vegetation and green and blue spaces in cities can support both climate change mitigation and adaptation goals, while also enhancing biodiversity and ecological health. Maibritt Pedersen Zari (Auckland University of Technology) explains why nature-based solutions (NbS) must be a vital part of urban planning and design.