www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cop26-cross-sectoral.html

Transition to a Cross-sectoral Approach for Decarbonising the Built Environment

By Thomas Lützkendorf (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, DE)

The sole reliance on a sectoral approach to GHG emission reductions is problematic and incomplete because it fails to engage with the complex array of built environment actors. A different conceptual and practical approach is proposed which involves 'areas of need' and 'areas of activity'. A scalable GHG budget for the built environment will be more effective in reducing built environment GHG emissions and allow actors to take more control over their emissions.

It is accepted that great efforts are needed to achieve a massive reduction in GHG emissions to net-zero. To do this effectively requires the definition and creation of GHG emission budgets for specific action areas and sectors. These budgets are necessary to develop reduction strategies and to introduce control mechanisms, (legal) requirements and incentives. This also applies to the construction, refurbishment, operation and use of construction works of all kinds, including buildings. This process is currently taking place in some countries. My expectation and hope is that the commitments made at COP-26 will lead to a scalable budget for the built environment that gives clarity to the many different actors involved and provides them with a clear set of metrics to achieve - both in the short and medium term.

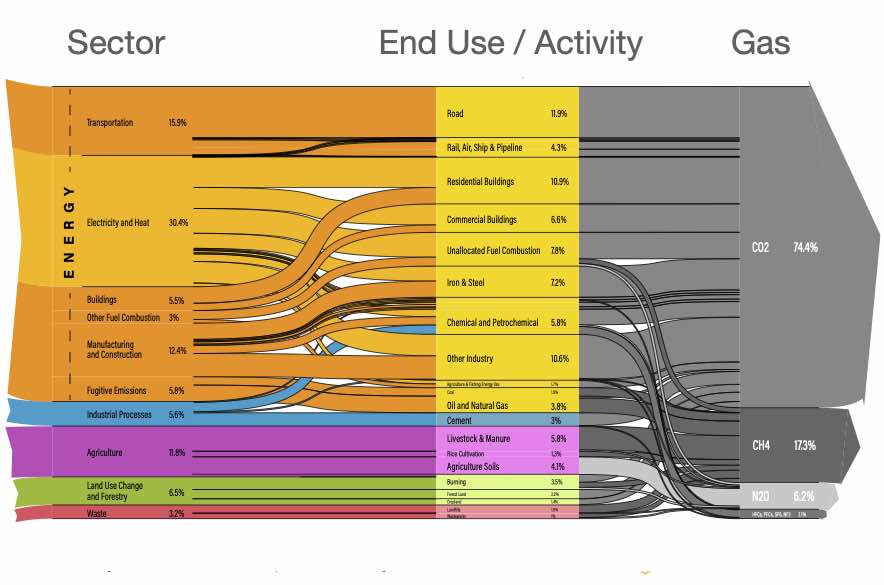

The creation of a specific GHG emission budget for the built environment will not be easy. Indeed, the various inputs for its creation, operation and maintenance span many sectors which makes the accounting or allocation of emissions difficult. In a sectoral analysis, the allocation of GHG emissions is complicated for the construction and real estate sector because of its overlaps with the energy sector, the (construction product) manufacturing industry, the transport sector, waste management sector and, in some cases, agriculture sector. If the indirect emissions assigned to the energy sector are added to the direct emissions from building operation, the share attributed to the operation of residential and non-residential buildings rises to 25-30% of energy-related CO2 emissions (GABC et al., 2019). If the emissions from the manufacturing of construction products for new buildings and refurbishments are included, the share of all building-related activities based on international and national studies is around 40% of all energy- and process-related CO2 emissions (GABC et al., 2019). This suggests the true magnitude of the built environment's impact. But net-zero CO2-emission buildings are not enough to save the climate. In future we must include all energy- and process-related GHG emissions into such statistics as well as related strategies.

A thematic approach via macroeconomic sectors is often chosen but is problematic and incomplete because:

- the contribution and importance of the built environment are underestimated

- the involved actors are not clearly identified,

- the indirect emissions and their reduction potential are not considered.

In macroeconomics, buildings (and the built environment) are not a sector - the term 'building sector' is misleading (Habert et al, 2020).

If we consider the built environment as an object of assessment, this overcomes the difficulties associated with the sectoral approach. The responsibility and influence for construction, refurbishment lie with investors and owners, the operation resides with users. A promising alternative to the sectoral approach is to consider the construction, refurbishment and operation of buildings as an 'area of action' and the use of buildings, e.g. for residential purposes, as a service or 'area of need'. The consideration of the 'areas of need' shows references to the personal carbon budget (Fuso Nerini et al., 2021) and thus also makes the connections clear for individuals. It is therefore proposed to make greater use of these perspectives when designing and implementing reduction targets:

- the 'area of activity'

- the 'area of need'.

The 'area of activity' perspective is particularly suitable for influencing the direct and indirect GHG emissions associated with the construction, refurbishment and operation of buildings. It is possible to address and involve all actors along the value chain. In the spirit of SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), the suppliers and consumers of construction products, services and buildings can make their contribution to SDG 13 (Climate Action). It is not enough to manufacture low carbon products and implement net zero emission buildings; they must be accompanied by demand-side 'pull', finance and 'value'. The development taking place in Europe with respect to developing a taxonomy (European Commission, 2021) will address demand and finance by providing preferential financial investment to projects that contribute to sustainable development. Real estate financing is a major focus and taxonomy already calls for the determination of a carbon footprint for buildings. Research projects such as IEA EBC Annex 72 (IEA, 2021) are clarifying the methodological basis for its calculation as well as assessment. This complements various national and local activities in Europe. The cross-sectoral approach at the economic level corresponds to the analysis, assessment and decisions involving GHG emissions when designing new construction and refurbishment measures, taking into account a life cycle related environmental performance assessment.

Society urgently needs to supplement the traditional sectoral approach to GHG emissions with cross-sectoral activities. Researchers, NGOs and policymakers need to actively explain and recommend this internationally. This is the only way to tap the enormous potential for reductions by the many different actors along the value chain, but also by built environment 'consumers' (e.g. clients, owners and tenants). In the spirit of Graz Declaration for Climate Protection in the Built Environment (SBE19 Graz, 2019) there is a need for scalable targets on national, regional, national & institutional building stock, city and building level including budgets as guidance for design, funding and legislation.

References

European Commission. (2021). EU Taxonomy Compass. https://ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance-taxonomy/activities/activity_en.htm?reference=7.1

GABC, IEA, UNEP. (2019). 2019 Global status report for buildings and construction: towards a zero-emission, efficient and resilient buildings and construction sector. https://bit.ly/3nOO2ff

Habert, G., Röck, M., Steininger, K., Lupisek, A., Birgisdottir, H., Desing, H., Chandrakumar, C., Pittau, F., Passer, A., Rovers, R., Slavkovic, K, Hollberg, A., Hoxha, E., Jusselme, T., Nault, E., Allacker, K., Lützkendorf, T. (2020). Carbon budgets for buildings: harmonising temporal, spatial and sectoral dimensions. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 429-452. http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.47

IEA. (2021). IEA EBC Annex 72: assessing life cycle related environmental impacts caused by buildings. https://annex72.iea-ebc.org/

Fuso Nerini, F., Fawcett, T., Parag, Y., Ekins, P. (2021). Personal carbon allowances revisited. Nature Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00756-w

SBE19 Graz. (2019). Graz Declaration for Climate Protection in the Built Environment. https://gd.ccca.ac.at/

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Urban verticalisation: typologies of high-rise development in Santiago

D Moreno-Alba, C Marmolejo-Duarte, M Vicuña del Río & C Aguirre-Núñez

A public theatre as a living lab to create resilience

A Apostu & M Drăghici

Reconstruction in post-war Rome: transnational flows and national identity

J Jiang

Reframing disaster recovery through spatial justice: an integrated framework

M A Gasseloğlu & J E Gonçalves

Tracking energy signatures of British homes from 2020 to 2025

C Hanmer, J Few, F Hollick, S Elam & T Oreszczyn

Spatial (in)justice shaping the home as a space of work

D Milián Bernal, J Laitinen, H Shevchenko, O Ivanova, S Pelsmakers & E Nisonen

Working at home: tactics to reappropriate the home

D Milián Bernal, S Pelsmakers, E Nisonen & J Vanhatalo

Living labs and building testing labs: enabling climate change adaptation

J Hugo & M Farhadian

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.