www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cop26-elephant.html

The Elephant in the Climate Change Room

By Mark Levine (Senior Advisor, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, US)

As the economies and cities in developing countries grow, they will represent the total global increase in GHG emissions through the end of this century. These countries currently have the least capability to limit GHG emissions. In addition to ensuring radical GHG emission reductions in developed countries, COP26 must also now provide a range of significant assistance to developing countries to create local capabilities to reduce emissions. A broad outline is presented of what this entails.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has expressed its view that "acceptable" levels of impact are compatible with a warming of only 1.5 to 2˚C; we are already 60% of the way to 1.5 ˚C temperature increase. Achieving a temperature increase of only 2˚C will be extraordinarily challenging, requiring a global drop in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 50% in 2050 and to zero by 2100. There are regions of the world that have the potential and may also have the political wherewithal to limit their emissions to be compatible with a 2˚C warming. These include Western Europe, China, Japan, the "Four Tigers" of S.E. Asia, and several countries in South America. India and the United States have the potential to follow a 2˚C path but face severe political barriers (very different in each country). Together, these countries represent less than 50% of current GHG emissions.

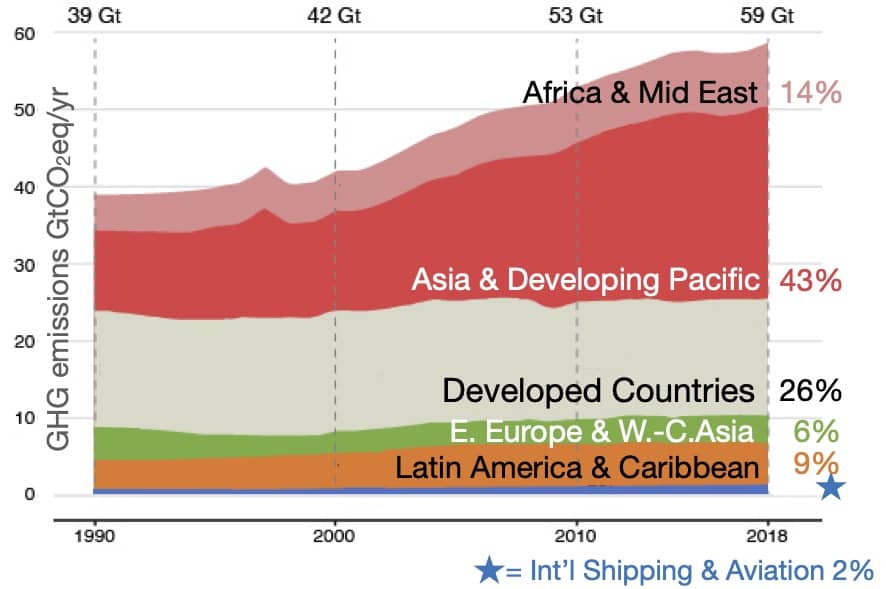

This leaves countries representing more than half the world's population, mostly developing countries, as major outliers. As their economies and cities grow, these countries will represent the total global increase in GHG emissions through the end of this century, as they have during the past three decades (see Figure 1). These countries have the least capability to limit GHG emissions.

It is imperative that there be developed plans and actions to enable developing countries to reduce emissions. As their cities are rapidly expanding, there is an opportunity now to create low-energy and zero-carbon infrastructure and buildings. Such plans need to include the following elements:

- Training for key participants in developing countries in measures and methods to reduce GHG emissions in scale

- Investment in "soft" infrastructure to identify technologies and to design and implement policies for reducing GHGs

- Incentives for investments in GHG mitigation (e.g., solar, wind, or nuclear electricity; energy efficiency for buildings and industry; new equipment to electrify buildings and industry; purchase of EVs)

- Equitable technology transfer to developing countries, making intellectual property available to them, and promoting local production and use

To carry this out, it will be necessary to:

- Create a new type of organization (or even better extend the remit of the Green Climate Fund) to handle the large-scale funding as well as to provide the soft investments that need to accompany the lending.In particular, it will be necessary to make the release of funds contingent on the country taking specific steps that will lead to reduction in GHG emissions.

- Establish one or more training centers in each of the major regions of the world; training would encompass all relevant aspects of design and implementation of GHG mitigation plans including, planning, policy development, finance, engineering, etc. Because most emissions result from activities in cities and buildings, there needs to be emphasis on policies and programs for them.

- Ensure that as large a percentage of the funds as possible are used in the developing countries in order to grow 'green' jobs and provide other benefits to those countries

A recent report of the Green Climate Fund (Hourcade et al., 2021, p. 12) notes the"

"misalignment [of investment] is compounded by the limited capital flows from high-savings to low-savings regions (mostly developing countries). . . .With an estimated $14 trillion of negative-yielding debt in OECD countries and $26 trillion of low carbon climate-resilient investment opportunities in developing countries by 2030. [C]apital seeking higher results should flow from developed countries to developing countries to address this gap. This is not happening. Three-quarters of global climate is deployed in the country in which it is sourced, revealing a strong preference for home-country investments where risks are well understood. This explains why sub-Saharan Africa accounts for only 5% of climate-related financial flows in non-OECD countries."

The redirection of investment flows and associated soft investments are urgently needed. It would be desirable for the leadership of the next (planning) step to be shared by the United States and China, working collaboratively. (China and the U.S. together account for a large portion of global emissions; they worked very effectively together to enable the agreement at the Paris meeting in 2015.) This call to action is both essential and long overdue. Addressing the issues of developing countries needs to be at the forefront of topics to be discussed in Conference of the Parties (COP) to be held starting at the end of October in Glasgow.

Reference

Hourcade, J.C; Glemarec, Y; de Coninck, H; Bayat-Renoux, F.; Ramakrishna, K., Revi, A. (2021). Scaling up climate finance in the context of Covid-19 - Executive Summary. South Korea: Green Climate Fund.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Acceptability of sufficiency consumption policies by Finnish households

E Nuorivaara & S Ahvenharju

Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse

É Savoie, J P Sapinski & A-M Laroche

Cooler streets for a cycleable city: assessing policy alignment

C Tang & J Bush

Understanding the embodied carbon credentials of modern methods of construction

R O'Hegarty, A McCarthy, J O'Hagan, T Thanapornpakornsin, S Raffoul & O Kinnane

The changing typology of urban apartment buildings in Aurinkolahti

S Meriläinen & A Tervo

Embodied climate impacts in urban development: a neighbourhood case study

S Sjökvist, N Francart, M Balouktsi & H Birgisdottir

Environmental effects of urban wind energy harvesting: a review

I Tsionas, M laguno-Munitxa & A Stephan

Office environment and employee differences by company health management certification

S Arata, M Sugiuchi, T Ikaga, Y Shiraishi, T Hayashi, S Ando & S Kawakubo

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Culture change in the UK construction industry: an anthropological perspective

I Tellam

Are people willing to share living space? Household preferences in Finland

E Ruokamo, E Kylkilahti, M Lettenmeier & A Toppinen

Towards urban LCA: examining densification alternatives for a residential neighbourhood

M Moisio, E Salmio, T Kaasalainen, S Huuhka, A Räsänen, J Lahdensivu, M Leppänen & P Kuula

A population-level framework to estimate unequal exposure to indoor heat and air pollution

R Cole, C H Simpson, L Ferguson, P Symonds, J Taylor, C Heaviside, P Murage, H L Macintyre, S Hajat, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Finnish glazed balconies: residents' experience, wellbeing and use

L Jegard, R Castaño-Rosa, S Kilpeläinen & S Pelsmakers

Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis

C C Nwagwu, S Akin & E G Hertwich

Mapping municipal land policies: applications of flexible zoning for densification

V Götze, J-D Gerber & M Jehling

Energy sufficiency and recognition justice: a study of household consumption

A Guilbert

Linking housing, socio-demographic, environmental and mental health data at scale

P Symonds, C H Simpson, G Petrou, L Ferguson, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Measuring health inequities due to housing characteristics

K Govertsen & M Kane

Provide or prevent? Exploring sufficiency imaginaries within Danish systems of provision

L K Aagaard & T H Christensen

Imagining sufficiency through collective changes as satisfiers

O Moynat & M Sahakian

US urban land-use reform: a strategy for energy sufficiency

Z M Subin, J Lombardi, R Muralidharan, J Korn, J Malik, T Pullen, M Wei & T Hong

Mapping supply chains for energy retrofit

F Wade & Y Han

Operationalising building-related energy sufficiency measures in SMEs

I Fouiteh, J D Cabrera Santelices, A Susini & M K Patel

Promoting neighbourhood sharing: infrastructures of convenience and community

A Huber, H Heinrichs & M Jaeger-Erben

New insights into thermal comfort sufficiency in dwellings

G van Moeseke, D de Grave, A Anciaux, J Sobczak & G Wallenborn

'Rightsize': a housing design game for spatial and energy sufficiency

P Graham, P Nourian, E Warwick & M Gath-Morad

Implementing housing policies for a sufficient lifestyle

M Bagheri, L Roth, L Siebke, C Rohde & H-J Linke

The jobs of climate adaptation

T Denham, L Rickards & O Ajulo

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Decolonising Cities: The Role of Street Naming

During colonialisation, street names were drawn from historical and societal contexts of the colonisers. Street nomenclature deployed by colonial administrators has a role in legitimising historical narratives and decentring local languages, cultures and heritage. Buyana Kareem examines street renaming as an important element of decolonisation.

Integrating Nature into Cities

Increasing vegetation and green and blue spaces in cities can support both climate change mitigation and adaptation goals, while also enhancing biodiversity and ecological health. Maibritt Pedersen Zari (Auckland University of Technology) explains why nature-based solutions (NbS) must be a vital part of urban planning and design.