www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/design-professionals-challenging-disasters.html

Design Professionals Challenging Disasters

Disasters are not natural occurrences. The design of cities and buildings can exacerbate or eliminate most disasters.

Ilan Kelman (University College London & University of Agder) explains why disasters are caused by humans - disasters come from a society's decisions and actions, not nature. Many disasters can be eliminated through design, regulation and social practices. Built environment professionals have a significant role in tackling disasters involving risk identification, assessment, and management. Vulnerability takes a long time to create or eliminate due to the slow evolution of most cities.

Disasters are not natural

Disasters have always been part of human existence, as have efforts to try to stop them-or, at least, to reduce their impact. Such efforts have become part of the essence of planning, designing, and constructing settlements and infrastructure. In fact, so much is known about how to prevent disasters, and the field of disaster research has become so extensive, that almost all disasters are considered to be human-caused. Consequently, the phrase "natural disaster" is preferably avoided, because disasters come from society, not nature.

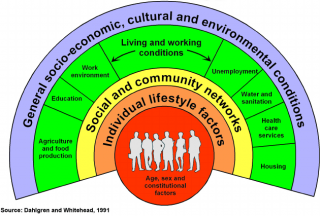

The reasoning is that, to get a disaster, two phenomena must combine: hazard and vulnerability. Examples of hazards often come from nature: earthquakes, storms, tsunamis, landslides, floods, droughts, microorganisms, meteorites, and space weather such as geomagnetic storms. Some happen quickly and some slowly. Yet a changing environment through a hazard is rarely a disaster, since the impact of the hazard is not known. People cope with it in different ways, sometimes successfully and sometimes less so.

This element of coping, how society deals or cannot deal with hazards, makes the disaster. It refers to vulnerability, i.e. being vulnerable to something, a societal process that creates the conditions whereby people and communities can be harmed by potential hazards. Here is where planning, design, construction, and maintenance of infrastructure and settlements make a significant difference.

Consider how many deaths worldwide have been caused by earthquakes in human history. This phrasing is deliberate, to focus on earthquakes as the cause. The answer is effectively zero. Almost no one in human history has had their cause of death as an earthquake, due to the mantra that earthquakes don't kill people, collapsing infrastructure does. The earthquake unfolds quickly as an event confined in space and time, but it took a long time and amorphous societal processes for the urban planning, building codes, construction, and lack of maintenance to manifest in such a way that infrastructure collapsed and killed people.

On 26 September 2003, a massive earthquake of moment magnitude 8.2 and shallow at just 27 kilometres below the surface hit northern Japan followed by a huge aftershock. No one died in the shaking, although one person was killed during the clean-up when a car hit them. Three months later, on 22 December a tremor of moment magnitude 6.5 and 8.4 kilometres deep shook central California, with two people dying when a tower fell on them as they exited their building.

Four days later, an earthquake of similar size and depth hit southern Iran, razing the city of Bam. More than 25,000 died, many when heavy roofs crushed them or their mud brick houses crumbled, suffocating them with the dust. Iran, like Japan and California, has world-renowned earthquake engineers and seismic research. If knowledge is not applied (via policy, regulation, social practices, etc.) to reduce vulnerability, then a disaster happens even with a moderate hazard.

This vulnerability takes a long time to create, since an earthquake-resistant or earthquake-vulnerable city cannot be built overnight. Dealing with vulnerability also means dealing with long-term social and environmental changes, of which human-caused climate change is a major influence on weather-related hazards. While many storms are decreasing in frequency due to climate change, their intensity is increasing, requiring design and maintenance responses to worsening wind, rain, and flooding. The main killer, though, is heat, with climate change pushing heat-humidity-time combinations into realms which are not survivable without cooling. A major long-term design challenge is upgrading and building cities to reduce vulnerability to the future's heat.

Designing for everyone's needs

In doing so, everyone's needs must be considered. A cyclone or tornado shelter with only stairs for entry could never meet everyone's requirements. People who use wheelchairs or who have just had a hip replacement would need to be carried into and out of the shelter. Such choices for buildings make some people vulnerable, because now they must request extra assistance and hope that someone is around who is willing and able to provide support. Consequently, the shelter cannot be fully effective. Building a ramp for each shelter and providing mobility assistance might sometimes cost more upfront, require long-term planning, and entail extra effort. Permitting deaths in disasters by designs creating vulnerability has incalculable costs. The choice is ours regarding which (financial, human, moral and social) costs we accept.

Producing, perpetuating, and tackling vulnerabilities ensues over the long-term, meaning that all disasters happen-and all disasters are prevented-slowly. Fast-onset disasters are as imaginary as natural disasters. Disasters are not extreme, unusual, or unpredictable events originating in the natural world. Fundamentally, disasters are not events. They emerge from the common, everyday, often unadmitted conditions in which we all live and which many of us are often powerless to stop. No matter what the environment does, the disaster results from humanity's values, behaviour, attitudes, activities, and ultimately decisions over the long-term.

The solutions are not just technical, instead they tend to be far more political and behavioural. They are about reducing inequity, injustice, and marginalisation, to permit everyone to have the equivalent opportunities for living and livelihoods. Many of these needed actions are far beyond the remit of architects, engineers, planners, and designers. Yet there is still plenty which these professions can and should do to tackle disasters. Professional training and organisations already incorporate extensive aspects of disaster risk identification, assessment, and management. Writing, critiquing, monitoring, and enforcing legislation, codes, and regulations have long been a core part, alongside balancing the level of voluntary and mandated approaches.

Designing for all risks?

How extensive should this work be and how much could the professions take on, morally, legally, financially, reputationally, and politically? Is there any limit to the risks falling within the remits?

Obesity kills many more people every year than earthquakes. In addition to designing for a location's seismic zone, structures and settlements could be designed for reducing obesity. Bicycle- and pedestrian-friendly cities are increasingly becoming the norm as are design guidelines for making buildings support physical activity by users and occupants. Changes at the micro-level can be effective, such as offering healthy food in canteens and vending machines while placing healthier choices in more prominent positions.

As another example, different vulnerabilities for women/girls and men/boys are continually created by society leading to disproportionate death tolls in disasters. In floods, more women/girls tend to die in South Asia yet more men/boys tend to die in the US. The disparities are attributed to the roles and expectations foisted on each, rather than physiological differences. In South Asia, women might not be permitted outside the home without an accompanying man and they are sometimes ostracised when menstruating, making evacuation difficult even when a flood warning is received and understood. In the US, men dominate rescue attempts by professionals and bystanders, with many of them dying due to poor equipment and training. Machoism might also play a role in taking risks.

Tackling engrained everyday sexism and culturally forced roles based on gender is not easy in design and planning. Researchers are investigating how to do so. One initiative called 'Choreographing the City' brings together engineers, planners, and choreographers to determine how dance could assist in understanding flows and movements in an urban setting. In determining how women/girls and men/boys experience and use urban spaces differently, insights emerge into changes which might promote equity, whether through discouraging catcalls or providing better lighting. All technical changes must happen in tandem with social changes making sexism and harassment unacceptable.

Ultimately, the impetus to tackle obesity, discrimination, and other challenges is political rather than technological. Roles nevertheless exist for planning, design, and construction professionals in lobbying for the changes; indicating how investment in the changes leads to reduced costs and many other benefits; and developing, writing, and testing the technical material while advocating for social change.

How far should this go in terms of everyday risks compared to every-millennium risks? Should some or all infrastructure withstand the impacts from all forms of volcanism, including supervolcanic explosive eruptions and flood basalts producing lava several storeys high along fissures which can extend dozens of kilometres? What size of space object, such as comets or meteorites, should be considered? What about ice ages or the Earth's magnetic field flipping? Where do collisions with rampaging elephants or kangaroos fit in?

Plenty of knowledge exists regarding infrastructure and settlements supporting or impeding the transmission of microbial pathogens. Maintaining and cleaning a building's water systems inhibits Legionnaires' disease. Automatic sliding doors, rather than those with handles which people must grasp, can reduce the spreading of flu and cold viruses. The Covid-19 pandemic has galvanised measures which have long been known to tackle droplet-borne viruses, from discouraging large crowds to mandatory hand sanitising.

Risks from zoonotic diseases can be addressed through the vectors. Avoiding water in eaves or potholes stops some mosquitoes from breeding. Landscaping and vegetation selection can reduce the prevalence of ticks and biting flies. Paving over green areas can substantially reduce the insect population, but then other risks increase such as stress, air pollution, and run-off when it rains.

Trade-offs begin to appear, many of which are reconcilable. Using permeable surfaces when paving permits rainwater to soak through, resolving some of the run-off concerns. Before 1995, Kobe, Japan had written its building codes under the assumption that typhoons were of higher concern than earthquakes, so roofs were heavy to withstand wind-related forces. On 17 January 1995, an earthquake led many of those roofs to crush occupants in the buildings. The decision could have been to address earthquake and wind forces simultaneously.

Could all possible risks always be addressed in all circumstances? The answer is more about a multiplicity of approaches rather than one-size-fits-all. Evacuating buildings and settlements, temporarily or permanently, is not necessarily a detrimental approach, provided that people have adequate time to leave, are ready for it through training and planning, do not lose too much in doing so, and are taken care of while evacuated. It is a long-standing dilemma in earthquake and tornado engineering about whether design should protect and preserve the building, and hence the occupants, or simply keep the building standing, so that the occupants can leave unharmed, even if the building is then condemned.

Balancing people's needs

As well, people have different needs. When a pandemic sweeps the world forcing mandated physical distancing (inappropriately termed 'social distancing', because we should remain as social as possible without physical proximity), how do people use buildings and cities differently? To ensure that people quarantined remain so, while others do not make non-essential journeys, should everyone's movements be tracked? Would this be the epitome of 'smart cities' or of invasive monitoring? Should infection prevention be dictated by the physical and mental health of the greatest number of people or of those labelled as the most vulnerable? Different ideologies rank differently the risk of getting sick and the risks from control of and access to personal data.

Defining the boundaries of how planning, design, construction, and maintenance should be implemented for all forms of risks is perhaps the greatest disaster-related challenge for professionals in these fields. This should always focus on reducing vulnerability, which means combining changes to hazards over the coming decades with changes to societies, technologies, and design philosophies.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.