www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/evidence-based-design.html

The Challenges of Evidence-Based Design

Challenges ahead: why urban planning and urban design need robust quantitative evidence for decision making.

While some progress has been made, particularly in areas like healing architecture where the impact of design on human well-being is more directly observable, much work remains to be done to extend evidence-based design to broader fields of architecture, urban planning and design. Meta Berghauser Pont (Chalmers University of Technology) explains the challenges and pathways needed for a shift toward evidence-based design in urban planning and urban design.

Evidence-based design (EBD) is increasingly seen as a critical methodology for urban development to address the multifaceted challenges that cities face today, such as climate change, spatial inequality, public health, and well-being (Wiley 2017). It is crucial that decisions about how the urban environment is transformed consider this and are evidence based (Hamilton 2003). However, EBD is not yet common practice (Pilosof and Grobman 2021), it requires a fundamental change in how knowledge is disseminated, research is conducted, architects and urban planners are trained, and how professional practice is organised.

EBD vs. best practice

Evidence-based design, which draws from the principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM), requires that design decisions are informed by the best available research. In contrast to the conventional design process that often relies on intuition, artistic inspiration, or precedent, EBD emphasizes the use of rigorous scientific evidence to guide decision-making.

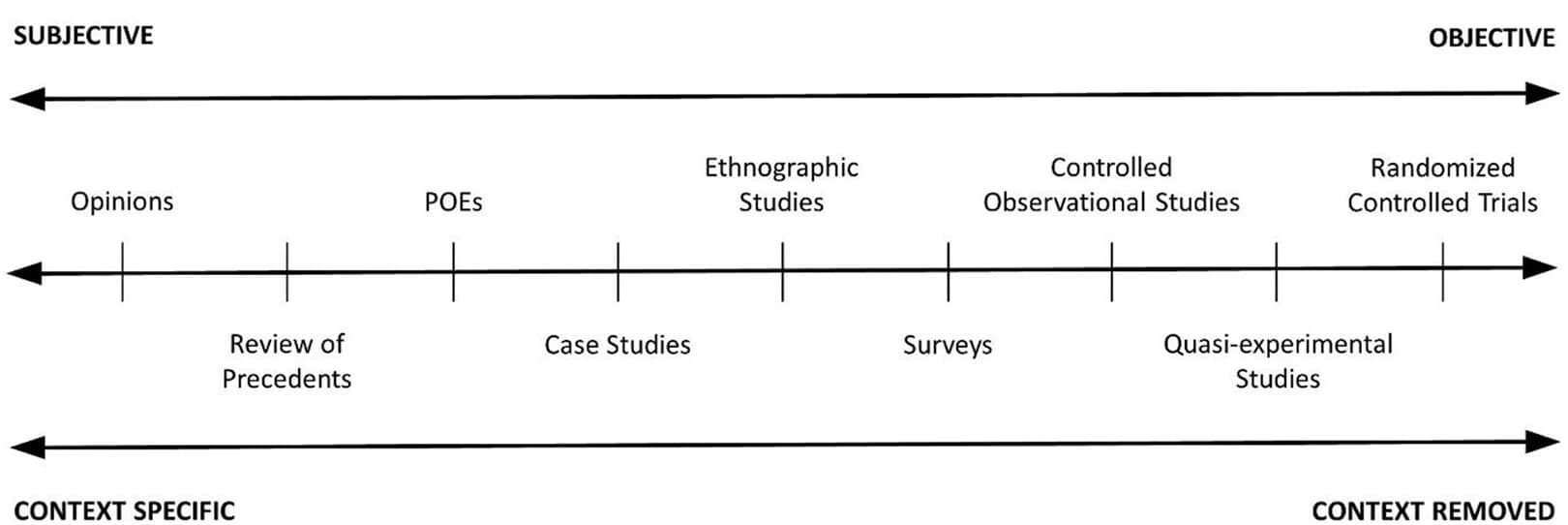

Evidence should not be confused with precedents, commonly referred to as 'best practice' in urban planning and design practice. Although best practice can provide good ideas, it lacks supporting theory to understand the mechanism why something works (Pilosof & Grobman 2021). Another misconception is to confuse evidence with proof. Evidence should instead be understood as it is defined in science, divided into gradients and only the highest levels consider causation. The use of precedents or 'best practice' covers the lowest level of evidence (is more subjective and context specific), while proven causation based on large samples covers the highest level of evidence, but hard to achieve in the field of urban planning and design (Figure 1).

Challenges related to EBD

One of the key challenges facing the urban planning and design research community is the lack of a solid infrastructure for evidence dissemination. In EBM, there are well-established systems for aggregating and updating research findings, such as databases, review journals, and systematic review methodologies. In contrast, the field of urban design lacks similar rigorously constructed methodologies (Sailer et al. 2009). While there is a growing body of research on how physical environments impact human behaviour and well-being, much of this research is scattered across disciplines, lacks standardization in methodologies and assessments, posing a challenge for meta-analysis, effective dissemination and the development of research informed planning and design practice.

The research base for EBD in urban planning is still relatively small, particularly in comparison to fields like medicine. Many of the existing studies are qualitative and context-specific, making it difficult to generalize findings. To build a robust foundation for EBD, there is a pressing need for more quantitative, longitudinal studies that can provide higher level evidence for decision-making. This involves not only conducting new research, but also developing mechanisms for synthesizing and summarizing existing research to make the findings more digestible and accessible to practitioners.

The interdisciplinary nature of urban planning and design presents another challenge. Research on the built environment spans a wide range of disciplines, including, besides urban planning and design, sociology, psychology, public health, and environmental science. Integrating findings from these diverse fields into a cohesive framework for EBD requires collaboration and communication across disciplinary boundaries. The lack of a common language or methodology can hinder efforts to apply research evidence in a practical context. The field of urban morphology and especially the analytical and mathematical approaches to urban morphology (Berghauser Pont 2018; D'Acci 2019) play a crucial role in developing such methods and indicators to describe the built environment. Linked to this, is the issue of data availability, where an important question is how these methods and indicators can be adapted and applied in different planning contexts, considering variations in data availability (Open Data Inventory n.d.).

Evidence and the research-practice gap

Slunge et al. (2017) show that a great deal of policy-relevant research is under-used or not used at all in policy planning or implementation and often research is not used to inform decisions but rather to back up decisions already made (e.g. Amara et al. 2004). Decision makers often don't 'know where to look' for evidence and struggle to distil practical implications from evidence (Hurleya et al. 2016).

An infrastructure that supports the dissemination of evidence such as platforms used in EBM could help connecting between evidence from research and real-life applications(Sailer et al. 2009). Such platforms should include databases, digests, and journals that summarize research findings and provide critical evaluations of their applicability to specific design challenges. The latter, ensuring that research findings are applicable to non-academic audiences will be key to bridging the gap between research and practice as Vliets (2009) points out.

Another key challenge in implementing EBD is to reform how urban planners and designers are trained. Part of this problem is the inherent ambiguity of design as an intuition-led practice and design as a scientific process of problem solving (Johnson 2009). Clearly, urban design and planning is neither of those since, quoting Karimi (2020, s. 2): 'it includes an iterative, interconnected series of explorations which sometimes is led by logical thinking and sometimes by intuitive creations'. Because design is considered a wicked or ill-defined problem, creative solutions are required, and this is what dominates many of the teaching curricula in architectural and urban design schools (Karimi 2020). This is not a problem per se, but the huge weight of generating creative ideas has put other stages of the design process, such as knowledge accumulation, design evaluation and design impact assessments to the background.

Incorporating EBD into education will require a shift from primarily focusing on generating ideas to evaluating these ideas. This will require the integration of research methods courses into the curriculum, as well as new pedagogical approaches that emphasize the use of evidence in design studios, i.e. architects and urban designers should be trained in how to use research to inform their design decisions.

Implementing EBD in the urban planning and design practice

The move toward EBD will also have significant implications for urban planning and design practice. Urban planners and designers will need to become more comfortable working with research evidence and incorporating it into their design decision-making processes. This will require a cultural shift in the profession, which has historically been more focused on creative problem-solving. Modification in the curricula of urban planning and design as discussed above will change this but will also take time. Therefore, the criticism of EBD (and EBM) being overly prescriptive, offering one-size-fits-all solutions to complex and context-specific problems must be addressed (Vliets 2009, Wiley 2017). This highlights the need for professional judgement to incorporate the uniqueness of individual patients and projects respectively, i.e., architect and urban designer need to find relevant research evidence and critically evaluate its quality and its applicability to specific situations.

Conclusions

The coming years are critical for EBD and requires changes on three levels: content, infrastructure and culture.

First, to increase the relevance of the vast number of studies on cities for the urban planning and design practice, the field of urban morphology has a critical responsibility to develop methods and indicators to describe the urban environment quantitatively. This also entails making such data available following the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Re-usable) principles, where national and European agencies (e.g. European Environment Agency and the Dutch building register BAG (Kadaster n.d.)) play a crucial role.

Second, to establish an infrastructure for aggregating and updating research findings. Within EBM, there are organizations that pool research data from multiple studies to reach stronger research conclusions e.g. Cochrane (n.d.), digests that compile structured abstracts (e.g. ACP Journal Club and Evidence-Based Medicine) and journals whose purpose is to summarize other journals.

Third and most challenging, a change in culture in the training and practice of urban planners and designers is required.

By grounding planning and design decisions in high level research evidence, urban planners and designers can create built environments that are aesthetically pleasing and responsive to key issues, including climate change and public health.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme, project 'Twinning towards research excellence in evidence-based planning and urban design', Grant Agreement No. 101078890.

References

Amara, N., Ouimet, M. & Landry, R. (2004). New evidence on instrumental, conceptual, and symbolic utilization of university research in government agencies. Science Communication, 26(1), 75-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547004 267491

Berghauser Pont, M. (2018). An analytical approach to urban form. In: Teaching Urban Morphology (ed. Vitor Oliveira), p. 101-123, Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-76126-8_7

Böröcz, Z. (2014). Design, crafts and architecture in Flanders: do they relate in education as in practice?, 9th Conference of the International Committee for Design History and Design Studies, 1(5).

Cochraine (n.d.) https://www.cochrane.org/

D'Acci, L. (2019). The mathematics of urban morphology, Birkhauser (part of the book series: Modelling and Simulation in Science, Engineering and Technology), Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12381-9

Hamilton, D. K. (2003). The four levels of evidence based practice. Healthcare Design, Vol. 3, 18-26.

Hurleya, J., Lamkerb, C.W. & Taylor, E.J. (2016). Exchange between researchers and practitioners in urban planning: achievable objective or a bridge too far? Planning, Theory & Practice, 17(3), 447-473.

Jenicek, M. & Stachenko, S. (2003). Evidence-based public health, community medicine, preventive care. Medical Science Monitor, Vol. 9(2), SR1-7.

Johnson, J. (2009). Embracing Complexity in Design. Routledge

Kadaster. (n.d.) Basisregistratie Adressen en Gebouwen (The Netherlands' Cadastre, Land Registry and Mapping Agency) https://www.kadaster.nl/zakelijk/registraties/basisregistraties/bag/over-bag

Karimi, K. (2020). Space Syntax as a platform for teaching analytical, research-based design: a pedagogical experience. Proceedings of the 12th Space Syntax Symposium.

Open Data Inventory n.d.).https://odin.opendatawatch.com/?aspxerrorpath=/Report/countryProfileUpdated/

Peavy, E. & Vander Wyst, K.B. (2017). Evidence-based design and research-informed design: what's the difference? Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 10(5), 143-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586717697683

Pilosof, N. P. & Grobman, Y.J. (2021). Evidence-based design in architectural education: designing the first Maggie's Centre in Israel. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 14(4), 114-129. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375867211007945

Sailer, K., Budgen, A., Lonsdale, N., Turner, A. & Penn, A. (2009). Evidence-based design: theoretical and practical reflections of an emerging approach in office architecture. Design Research Society Conference, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK, 16-19 July 2008.

Slunge, D., Drakenberg, O., Ekbom, A., Göthberg, M., Knaggård, Å. & Sahlin, U. (2017). Stakeholder Interaction in Research Processes - a Guide for Researchers and Research Groups. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Tvedebrink, T. D. O. & Jelic, A. (2021). From research to practice: is rethinking architectural education the remedy? Proceedings from Trondheim ARCH19 Conference, Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 14(1), 71-86.

Viets, E. (2009). Lessons from evidence-based medicine: what healthcare designers can learn from the medical field. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal. Vol. 2(2), 73-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/193758670900200207

Wiley, K. (2017). Tackling the application gap: architecture students' experiences of a research component in a design studio class (Master's thesis, University of Calgary, Canada). https://doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/27967

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.