www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/heat-pump.html

Heat Pump Market Transformation: Strategies & Lessons

What is an effective set of policies and strategies to deliver heat pumps to homes?

The UK Government has pledged to install 600,000 heat pumps per

year by 2028, up from 50,000 today. As we await the release of the UK Government's

Heat and Buildings Strategy, Aaron Gillich (BSRIA LSBU Net Zero Building Centre) reflects on what constitutes effective strategy in terms of delivery, and how industry can help drive the low carbon transition.

The principle of market transformation requires a portfolio of policies and actions to create a range of market effects that are eventually self-sustaining. It requires strong policy support, but also an engagement with end users.

The lens of the CEREB Framework (Gillich et al., 2018) for retrofit market transformation is highly appropriate for heat pumps. The CEREB Framework was created by comparing 50 market transformation programmes across the UK, US, and Canada, and distilling them to five pillars that together can build capacity for sustained change in a market: (1) programme design, (2) outreach and marketing, (3) workforce engagement, (4) financing and incentives and (5) data and evaluation.

Pillar 1: Programme design

The first pillar in the CEREB Framework calls for an understanding

of the existing policy landscape, and in particular the gaps in local

networks. Any programme seeking change

should strive to complement, not duplicate existing efforts, and leverage the

participation of local actors with knowledge of the relevant supply

chains.

The current market for heat pumps is famously weak at this type of networking and integration in the UK. National and local policies are not well coordinated, and there are few existing supplier networks that local authorities and advocacy groups can link with to help deliver heat pumps at scale.

Both the Big Switch in the UK and the switch to heat pumps in Finland offer useful insights into the role of organisation and local deployment in a heat transition.

From 1960-1977, the UK carried out the Big Switch from town gas to natural gas. The government coordinated a nationalised Gas Council and Area Boards with industry groups, appliance manufacturers, installers, and marketing campaigns so that gas central heating reach almost half all homes (Sovacool & Martiskainen, 2020). They converted 40 million appliances and 14 million homes, averaging around 1 million homes per year and peaking at over 1.6 million in one year at the height of the campaign.

The Big Switch benefited from strong central organisation that was delivered through the nationalised Gas Council and Area Boards.1 It is highly unlikely that the low carbon heating landscape will be dominated by a single technology in the way that natural gas has dominated fossil fuel heating.2 This means that the levers utilised to drive centralisation and market transformation in the Big Switch will not be deployed in the same way for the low carbon heat transition.

Finland quite famously grew their heat pump market from 1500 in 2000 to 930,000 in 2018, roughly one third of households.3

Sovacool & Martiskainen (2020) carried out a review of heat transitions and found that one of the common strengths among successful heating market transformations was a strong coordination between local, state, and national scale efforts. In the UK, local authorities will decide and deliver many critical zoning and distribution aspects of low carbon heating technologies. They are currently under-resourced to do this and insufficiently supported by national frameworks.

In order to galvanise the heat pump industry in Finland, the national and cross-sectoral heat pump association SULPU was established in 1999 at the beginning of their heat pump campaign. This body played a critical role in organising the industry and liaising with government on policymaking, as well as gathering data to support in evaluation and improvement. The UK has several trade organisations promoting heat pumps, but they have not galvanised to create a cohesive and compelling message to consumers.

The UK has no single body that fulfils the role that the SULPU played in the Finland transition. All signs from policies announced so far suggest that they will look for the heat pump industry to galvanise itself. One effective option for the UK would be following the RAP suggestion of establishing a UK Heat Pump Council formed by national and local government, regulators, industry, and civil society to coordinate simple and effective consumer engagement and protection.4

Pillar 2: Outreach and marketing

Having created the enabling networks to reach the relevant actors

in the market (pillar 1), the remit of the second pillar is harnessing those

networks to engage end users in an ongoing conversation that makes heat pumps

an acceptable and desirable choice for consumers.

Market transformation research repeatedly shows that unidirectional marketing campaigns are essential for creating awareness at the outset of a programme. The 'Guaranteed warmth' campaign is an excellent example of the gas industry employing this principle during the Big Switch.

However, for a sustained market transformation, the programme must move from awareness campaigns to more personal outreach through direct bilateral engagement with end users. Here Finland offers a useful example in their heat pump switch. In the early 2000s, Finland created user-led online heat pump discussion forums. This created platforms for discussion and unofficial advice on sizing, costs, and consumer preferences. Much like the UK, there was the perception that heat pumps were not suitable for colder homes, and these user forums were important in driving user-led innovations (Sovacool & Martiskainen, 2020).

The UK faces an uphill battle in normalising heat pumps in the public discourse. We largely hold the idea of heat and gas to be synonymous. Nearly half of UK respondents haven't even heard of air source and ground source heat pumps (BEIS, 2021a). This number has stayed relatively consistent in recent years, despite widespread increase in awareness and concern about climate issues.

There are differing views on who is responsible for raising awareness of heat pumps in the UK (Martiskainen et al., 2021). As noted, the groups such as the Heat Pump Association (HPA) and Ground Source Heat Pump Association (GSHPA) and others have not succeeded in creating a compelling and organised message. The gas industry on the other hand is very effective and coordinated in its messaging, as observed only weeks ago when the big four boiler firms released a shared vow that hydrogen boilers will cost no more than gas boilers.5

This coordination originated in the Big Switch itself and has benefited from incumbency bias in the public discourse ever since. By its own admission, the HPA struggles to compete with its limited resources. While the user-led forums helped drive heat pump demand in Finland, the gas incumbency in the UK has created an absence of active user involvement in heat pumps that hampered both niche construction and regime destabilisation (Martiskainen et al., 2021).

Pillar 3: Workforce engagement

Source:

Workforce engagement holds an important place in market transformation programmes. Most programmes include a certification or standard such as PAS 2035, Gas Safe, or Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS). In some cases, the programme can simply drive demand and then rely on the workforce to uptake the necessary skills and certifications through financial self-interest and market forces.

However, market forces insufficiently reward higher skill levels for the workforce to invest in the training in the timescales needed. A dedicated push is required, e.g. a direct subsidy for the training. Successful market transformation programmes, such as the Big Switch and Finland's heat pump transitions, placed a considerable emphasis on both creating new training and certification standards, and supporting the workforce in undertaking that training.

The UK is often reluctant to subsidise training programmes: most UK programmes with market transformation goals simply focus on the certification standard and neglect direct support for the workforce to take up that standard. Requiring a certification like Trustmark in order to access government funding programmes is a useful but insufficient driver for uptake. The unregulated nature of such vocational training, and the lack of adherence to a common syllabus is problematic (Gleeson, 2016). A widespread reform agenda for UK construction education and practice has been proposed to address structural employment issues as a pillar for retrofit market transformation (Killip, 2020).

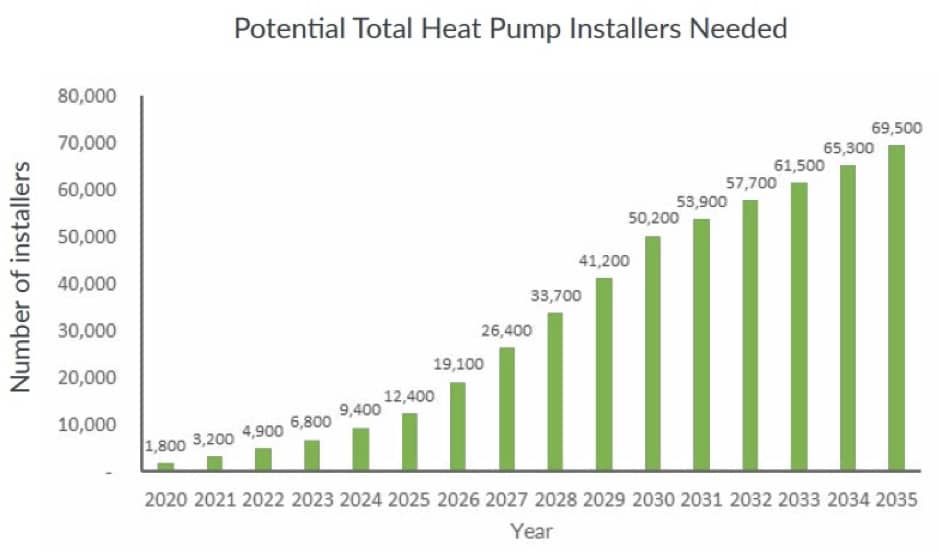

The HPA argues that they already have the capacity in place to train up to 7000 installers each year, enough to reach their 2027 projection (Figure 1), and what is missing is compelling signals from government to build the market. HPA have called for funding to directly support heat pump training, noting that training for MCS certification for heat pumps costs roughly double the cost of Gas Safe training, and incurs around four times the annual renewal fee.

Pillar 4: Financing and incentives

Source:

The life cycle cost of a heat pump is roughly double that of a gas boiler over 20 years. This is due both to higher fuel costs of electricity relative to gas, and also to the higher capital cost of the heat pump itself. To be acceptable to consumers and provide affordable warmth, both the capital and operational costs of heat pumps must be addressed via flexible (lower) tariffs and a change in taxes/fuel levies. Energy demand reduction is also a priority (and will also reduce operational costs). This will often require concurrent improvement to the heating distribution system and/or the building fabric.

Upfront costs and ongoing costs are almost always handled at different stages in a market transformation programme. Typically, a grant or direct rebate is used to drive early demand and climb the steep part of the market transformation curve. As the market becomes more established, these grants are often reduced or used as 'sweeteners' to drive uptake of loan programmes in the longer term. Public funds are often used to support loan programmes at first, for example by buying down interest rates, with the aim being for that support to be decreased over time until commercial lending at competitive rates takes over. At this point these capacity building mechanisms have transformed the market sufficiently that regulatory measures such as minimum performance standards can be implemented effectively.

The UK has not followed this pattern of 1) grants, 2) publicly supported financing, 3) commercial lending in its approach to driving heat pumps. The flagship low carbon heating programme for most of the past decade has been the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI). The RHI is not a financing scheme in the traditional sense, but does use public funds to reduce ongoing costs. The homeowner is responsible for the upfront capital cost and then pays a reduced price over the lifetime of the measure, similar to a low interest loan.

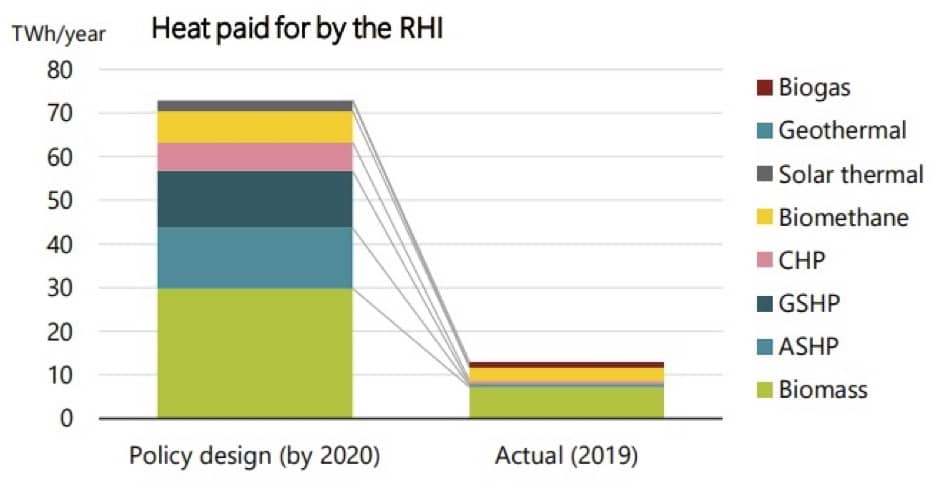

The RHI has dramatically underperformed against expectations (Figure 2). While there are many reasons for this, principle among them is that the RHI did not reduce the upfront cost of the heat pump, effectively skipping the first step needed to climb the steepest part of the market transformation curve.

The RHI will end in 2022 and be replaced by the Clean Heat Grant, likely to be a rebate of ~£5,000 on the upfront cost of a heat pump. This will almost certainly help drive demand for heat pumps in the short term, however it will only run for three years. The RHI and the Clean Heat Grant have effectively come in the wrong order, and do not fit with the conventional approach to building capacity in the market in the longer term. Regulatory drivers such as the Future Homes Standard will come into force by 2025, but overall the combination of grants and regulatory measures leaves a significant policy gap.6

The Finland transition was more successful in reducing cost barriers while creating stable long-term signals to build capacity in the market. In 2001, near the beginning of their heat pump transition, Finland reduced taxes on labour costs for home renovations, including heat pump installations. This is credited as being a major driver in the longer-term uptake of heat pumps.

Pillar 5: Data and evaluation

Evaluation for market transformation should not focus on the results of a single programme, but rather at the combined market impacts of the portfolio of programmes. The range of desired market effects should be defined, and then programme actions and indicators created to target each market effect. Evaluations should focus not only on outcomes but on process and provide interim feedback for iterative improvements.

In Finland the heat pump association SULPU in particular developed tools to track and compile statistics on the sector's development and growth. These were shared with government and used to improve programme efforts. The Big Switch was similarly hailed as a process of continuous experiment and innovation.

The UK government continually reviews the market impacts of the RHI and the Heat Networks Investment Programme (BEIS 2021b). They measure not only the outcome indicators such as the number of low carbon heating systems installed, but also the wider market effects such as the number of installers, general awareness of the customer base, and the cost efficiency of the supply chain. They have found that 'market efficiency and innovation indicators suggest little progress to date, but potential for improvement in the future.' (BEIS 2021b) Both the RHI and the HNIP largely focus on cost barriers, and it is unrealistic to transform a complex and fragmented market with cost signals alone. Based on their own market effects data, a more active approach to both consumer and workforce engagement is clearly needed.

Conclusions

The UK has a laudable target for 600,000 heat pump installations per year by 2028. I think this is an achievable target that should be viewed as an essential step for transforming the UK into a net zero carbon society. But this will be an uphill battle to end the half-century reign of natural gas as the UK's dominant heat source.

Lessons from market transformation reveal the critical role that strong government action plays in creating a long-term transition. But it also highlights the role of the end user and the extent to which stakeholders must work together. The example of Finland's SULPU shows the need to galvanise industry.

Organisational networks must be created and used to drive a national conversation and public engagement - to reach the other half of the UK that still hasn't heard of heat pumps.

We eagerly await the publication of the UK Heat and Buildings Strategy. However, central government actions alone will not transform the heat pump market as significant local authority and industry leadership are crucial ingredients, particularly over the next few years as we climb the steepest part of the market transformation curve.

Notes

1 One of the key features that distinguishes 'the Big Switch' from the current low carbon heating transition is the homogeneity of the solution. In the 1960s, government provided very direct support to not only train gas boiler installers, but also create the drivers to address supply chain fragmentation and unify the market.

2 Unicorn or Silver Bullet? Filling Evidence Gaps on Decarbonising Heat. Presentation by Jon Saltmarsh, Deputy Director of Engineering and Research, Science and Innovation for Climate and Energy, BEIS, 24 June 2021, LSBU Climate Emergency Event

4 https://www.raponline.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/RAP-Heat-Pump-Policy-0324212.pdf

5 https://www.h2-view.com/story/hydrogen-ready-boilers-will-cost-no-more-than-natural-gas-variants-confirms-the-uks-four-largest-boiler-manufacturers/

References

BEIS (2021a) BEIS Public Attitudes Tracker (December 2020, Wave 36, UK). London: UK Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/959601/BEIS_PAT_W36_-_Key_Findings.pdf

BEIS (2021b) Low carbon heating metrics 2020: progress on developing a sustainable market.

London: UK Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/970298/low-carbon-market-metrics-2020.pdf

Gillich, A. Sunnika-Blank, M. & Ford, A. (2018). Designing an 'optimal' domestic retrofit programme. Building Research & Information, 46(7), 767-778. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2017.1368235

Gleeson, C.P. (2016). Residential heat pump installations: the role of vocational education and training. Building Research & Information, 44(4), 394-406. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2015.1082701

Killip, G. (2020). A reform agenda for UK construction education and practice. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 525-537. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.43

Martiskainen, M., Schot, J. & Sovacool, B.K. (2021). User innovation, niche construction and regime destabilization in heat pump transitions.Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 39, 119-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.03.001

Sovacool, B.K. and Martiskainen, M. (2020). Hot Transformations: governing rapid and deep household heating transitions in China, Denmark, Finland and the United Kingdom. Energy Policy, 139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111330

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.