www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/hi-res-model.html

Why High-Resolution Climate Modelling Matters: Cities and Health

By Clare Heaviside (University College London - UCL), Jonathon Taylor (UCL & Tampere U), Oscar Brousse (UCL), Charles Simpson (UCL)

Current and projected temperatures simulated by global climate models are typically output at a coarse resolution of 30-100 km. This is unhelpful for identifying climate-related public health risks in cities. New mapping is needed at higher resolution to better characterize hazards and prepare location-specific adaptation plans.

The range of negative health impacts of exposure to heat is widely researched and acknowledged (Basu, 2009). In the UK, around 2,000 deaths per year are attributed to heat (Hajat et al, 2014). Heat exposure is of particular concern due to: i) global observations of rising temperatures; ii) more frequent heatwaves associated with climate change, and iii) rising urban populations, who are exposed to the urban heat island (UHI) effect (Field et al., 2012; Melorose et al., 2015).

Risk assessments use relationships between ambient temperature and health outcomes such as risk of hospitalization or mortality to estimate health burdens for specific populations, e.g. the fraction of all-cause mortality which can be attributed to heat. By using projected temperatures derived from climate models, it is also possible to assess the potential change in health impacts we might expect in future (Gasparrini et al., 2017). These risk estimates are informative to policy makers for planning health and social care provisions, particularly in anticipation of heatwave events (Public Health England, 2015), or for designing mitigation and adaptation actions to protect health in future.

One source of uncertainty in climate change risk assessment relates to the type and resolution of exposure (temperature) data input to the risk assessment model, for example global-scale climate models are not designed to capture local or regional scale features, due to their coarse resolution (~30-100 km) (Goodess et al., 2021). This has particular importance for the UHI, because global climate model outputs do not represent the urban impact on the local climate, and therefore underestimate population heat exposure, and related public health impacts.

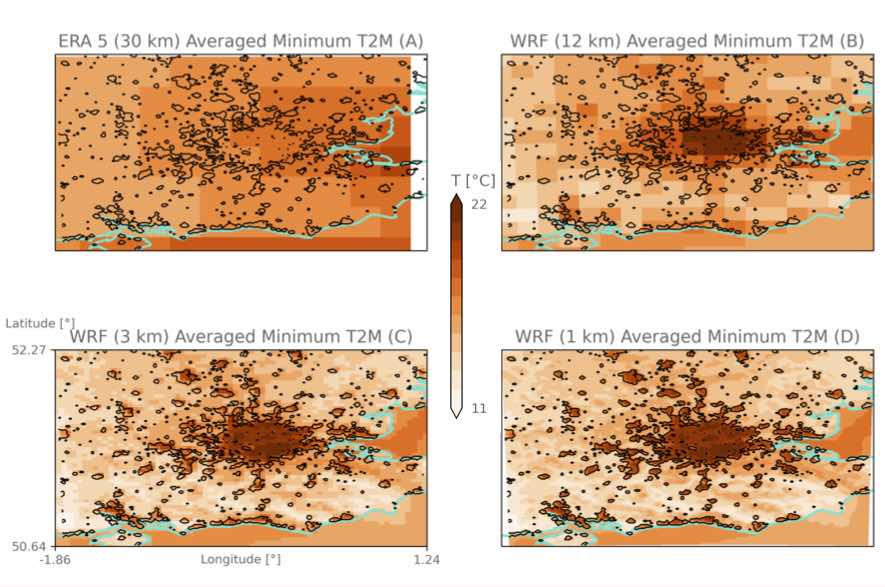

One solution is to use higher resolution climate or

meteorological modelling. This can be computationally expensive and difficult

to set up and run over large areas, but it can be effectively employed for

specific cities or regions to better represent temperatures across urban areas

(e.g. London, Figure 1). Previous simulations using a 1x1 km resolution

meteorological model for Birmingham in the UK estimated that the UHI

contributes up to 40% of heat-related mortality over a summer, (Macintyre & Heaviside, 2019) and up to 50% during a

heatwave (Heaviside et al., 2016). Estimates of heat-related

risks in the future without such highly resolved data might therefore be

underestimated by a half.

Action

Climate change risk assessment models are an important component of local adaptation strategies. They need to be used by policy makers, strategists, planners and stakeholders to assess potential future impacts of climate change, and to develop actions that will reduce risks. Quantitative estimates of societal risk are essential for long term planning, but local and city scale analysis provides necessary detail to reveal the extent to which a population is exposed or is vulnerable to the effects of heat. This vulnerability depends on multiple factors, including local climate, geography, housing and social and economic factors (Macintyre et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2018).

Additional city-scale modelling and spatial analysis (based

on high-resolution climate modelling) must add demographic data to 1) identify

vulnerable population groups or geographical areas; 2) investigate the impacts

of potential city-level and neighbourhood-level interventions, and 3) reduce health

inequalities and the potential for unintended consequences from adaptation

measures at local scales. This will enable strategists, planners and others in central

and local government to more effectively prepare appropriate adaptation

responses and focus efforts where they can have the greatest benefit to health

and wellbeing, and to society as a whole.

Acknowledgements

CH is supported by a NERC fellowship (NE/R01440X/1) and acknowledges funding from the Wellcome Trust HEROIC project (216035/Z/19/Z), which funds OB and CS.

References

Basu, R. (2009). High ambient temperature and mortality: A review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-8-40

Field, C. B., Barros, V. R., Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Dokken, D. J., Ebi, K. L., … Midgley, P. M. (2012). Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1-594. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139177245

Gasparrini, A., Guo, Y., Sera, F., Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M., Huber, V., Tong, S., … Armstrong, B. (2017). Projections of temperature-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios. The Lancet Planetary Health, 1(9), e360-e367. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30156-0

Goodess, C., Berk, S., Ratna, S. B., Brousse, O., Davies, M., Heaviside, C., Moore, C. & Pineo, H. (2021). Climate change projections for sustainable and healthy cities. Buildings and Cities, 2(1), 812-836. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.111

Hajat, S., Vardoulakis, S., Heaviside, C., & Eggen, B. (2014). Climate change effects on human health: Projections of temperature-related mortality for the UK during the 2020s, 2050s and 2080s. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(7), 641-648. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-202449

Heaviside, C., Vardoulakis, S., & Cai, X.-M. (2016). Attribution of mortality to the urban heat island during heatwaves in the West Midlands, UK. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-016-0100-9

Macintyre, H. L., & Heaviside, C. (2019). Potential benefits of cool roofs in reducing heat-related mortality during heatwaves in a European city. Environment International, 127, 430-441. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVINT.2019.02.065

Macintyre, H. L., Heaviside, C., Taylor, J., Picetti, R., Symonds, P., Cai, X.-M., & Vardoulakis, S. (2018). Assessing urban population vulnerability and environmental risks across an urban area during heatwaves - Implications for health protection. Science of the Total Environment, 610-611, 678-690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.062

Melorose, J., Perroy, R., & Careas, S. (2015). World population prospects. United Nations, 1(6042), 587-592. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Taylor, J., Symonds, P., Wilkinson, P., Heaviside, C., Macintyre, H., Davies, M., … Hutchinson, E. (2018). Estimating the influence of housing energy efficiency and overheating adaptations on heat-related mortality in the West Midlands, UK. Atmosphere, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos9050190

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Acceptability of sufficiency consumption policies by Finnish households

E Nuorivaara & S Ahvenharju

Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse

É Savoie, J P Sapinski & A-M Laroche

Cooler streets for a cycleable city: assessing policy alignment

C Tang & J Bush

Understanding the embodied carbon credentials of modern methods of construction

R O'Hegarty, A McCarthy, J O'Hagan, T Thanapornpakornsin, S Raffoul & O Kinnane

The changing typology of urban apartment buildings in Aurinkolahti

S Meriläinen & A Tervo

Embodied climate impacts in urban development: a neighbourhood case study

S Sjökvist, N Francart, M Balouktsi & H Birgisdottir

Environmental effects of urban wind energy harvesting: a review

I Tsionas, M laguno-Munitxa & A Stephan

Office environment and employee differences by company health management certification

S Arata, M Sugiuchi, T Ikaga, Y Shiraishi, T Hayashi, S Ando & S Kawakubo

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Culture change in the UK construction industry: an anthropological perspective

I Tellam

Are people willing to share living space? Household preferences in Finland

E Ruokamo, E Kylkilahti, M Lettenmeier & A Toppinen

Towards urban LCA: examining densification alternatives for a residential neighbourhood

M Moisio, E Salmio, T Kaasalainen, S Huuhka, A Räsänen, J Lahdensivu, M Leppänen & P Kuula

A population-level framework to estimate unequal exposure to indoor heat and air pollution

R Cole, C H Simpson, L Ferguson, P Symonds, J Taylor, C Heaviside, P Murage, H L Macintyre, S Hajat, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Finnish glazed balconies: residents' experience, wellbeing and use

L Jegard, R Castaño-Rosa, S Kilpeläinen & S Pelsmakers

Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis

C C Nwagwu, S Akin & E G Hertwich

Mapping municipal land policies: applications of flexible zoning for densification

V Götze, J-D Gerber & M Jehling

Energy sufficiency and recognition justice: a study of household consumption

A Guilbert

Linking housing, socio-demographic, environmental and mental health data at scale

P Symonds, C H Simpson, G Petrou, L Ferguson, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Measuring health inequities due to housing characteristics

K Govertsen & M Kane

Provide or prevent? Exploring sufficiency imaginaries within Danish systems of provision

L K Aagaard & T H Christensen

Imagining sufficiency through collective changes as satisfiers

O Moynat & M Sahakian

US urban land-use reform: a strategy for energy sufficiency

Z M Subin, J Lombardi, R Muralidharan, J Korn, J Malik, T Pullen, M Wei & T Hong

Mapping supply chains for energy retrofit

F Wade & Y Han

Operationalising building-related energy sufficiency measures in SMEs

I Fouiteh, J D Cabrera Santelices, A Susini & M K Patel

Promoting neighbourhood sharing: infrastructures of convenience and community

A Huber, H Heinrichs & M Jaeger-Erben

New insights into thermal comfort sufficiency in dwellings

G van Moeseke, D de Grave, A Anciaux, J Sobczak & G Wallenborn

'Rightsize': a housing design game for spatial and energy sufficiency

P Graham, P Nourian, E Warwick & M Gath-Morad

Implementing housing policies for a sufficient lifestyle

M Bagheri, L Roth, L Siebke, C Rohde & H-J Linke

The jobs of climate adaptation

T Denham, L Rickards & O Ajulo

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Decolonising Cities: The Role of Street Naming

During colonialisation, street names were drawn from historical and societal contexts of the colonisers. Street nomenclature deployed by colonial administrators has a role in legitimising historical narratives and decentring local languages, cultures and heritage. Buyana Kareem examines street renaming as an important element of decolonisation.

Integrating Nature into Cities

Increasing vegetation and green and blue spaces in cities can support both climate change mitigation and adaptation goals, while also enhancing biodiversity and ecological health. Maibritt Pedersen Zari (Auckland University of Technology) explains why nature-based solutions (NbS) must be a vital part of urban planning and design.