www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/housing-adaptability-lessons.html

Housing Adaptability: Some Past Lessons

Past research on housing is still relevant to today's research and policy agendas.

The issues of how housing can be adaptable are not new. Construction historian Andrew Rabeneck reflects on research and practice from the 1970s that should be included in current conversations. Several different strategies exist: Limited Flexibility, Full Flexibililty, Build On (at a later date), Build In (at a later date), Adaptability (through the provision of extra space). One of the simplest and least cost options is the enhanced space provision i.e. an increase in room areas of up to 10% and looseness of fit - allowing 'occupant choice through ambiguity', with minimum predetermination of patterns of use.

Nearly half a century ago I co-authored two very extensive articles in Architectural Design about housing flexibility and adaptability (Rabeneck et al., 1973, 1974). This was a potent topic then, as it is now, because space standards for public housing were under pressure from government and rampant inflation in the wake of oil price rises was causing a serious diminution in standards for typical housing offerings in both the public and private sectors. The result was rapid obsolescence of housing and early physical deterioration often leading to premature demolition. Some form of flexibility seemed to offer attractive antidotes, both technically and because it promised some freedom of choice for occupants. Flexibility, then as now, fascinated quite a few architects.

The first of our two articles described projects for flexible housing from all over Europe, Scandinavia and the UK. Our research into models of European housing flexibility was funded by a major manufacturer.[1] What we found were several different existing approaches to providing some flexibility in housing, from demountable partitions to occupant layout planning systems, as well as financial incentives and provision for future expansion, etc. Thirty projects were documented (all of which we visited) representing widespread response to growing constraints on housing.

The second article analysed what we had found. Regardless of how the problem was defined, each approach to flexibility took the form of insurance against predicted life events. As such, each entailed a degree of overprovision of some feature or performance attribute of the housing, above what might be considered a 'normal' base. Measuring the value of the overprovision, absolutely and in terms of opportunity cost, lay at the heart of our analysis. In contrast to more recent work by Till & Schneider (2007) that avoids discussion of the cost implications of flexibility, we considered cost to be fundamental to any proposal. We therefore made detailed cost analyses for five models of flexibility using a methodology developed by Philip Stone at the Building Research Establishment (Stone, 1970). The models and their premiums above conventional construction cost at the time (based on an analysis of 25 projects built between 1968-1971), were:

- Limited Flexibility (10% additional cost)

- Full Flexibililty (26% additional cost)

- Build On at a later date (4.5% additional cost)

- Build In at a later date (8% additional cost)

- Adaptability - 6.5% extra space - (5% additional cost).

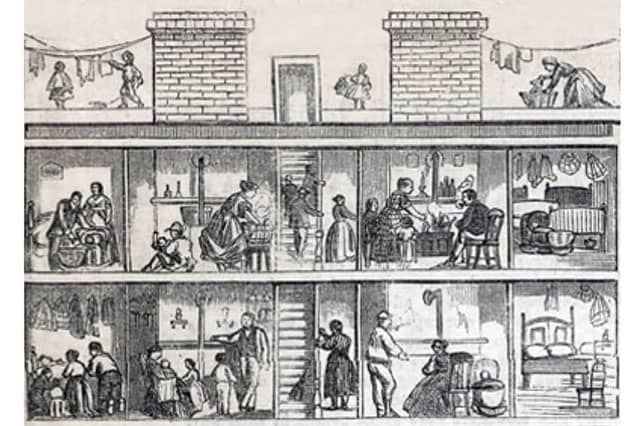

The analysis showed clearly that adaptable solutions, relying on enhanced space provision, provide the best hedge against future uncertainty and rising living standards at the lowest cost. The adaptable approach, in contrast to flexibility that depends on technical overprovision or demountable systems that rapidly obsolesce, or those requiring future additional capital (Build In and Build On), emphasises planning and layout more than construction technique. It is based on carefully considered variations in room sizes, relationship between rooms, distribution and positioning of services, slightly generous useable floor area, generous openings between spaces and minimum overt expression of room function. The article also provided a survey of housing designs that display adaptable characteristics. Successful examples of these included:

- Mesopotamian and Mediterranean hot climate courtyard houses

- The Northern counterpart, of an enclosed hall surrounded by smaller spaces within thick outer walls

- The meeting of North and South in Palladian villas, composed of ambiguous rooms

- Japanese tatami mat houses with screen dividers

- European speculative housing of the 18th and 19th centuries

- Some late 19th and early 20th century houses by Loos, Behrens, Baillie-Scott, Rietveldt

- Houses in Barriadas and Bidonvilles where the user is in control and planning choices are unselfconscious

- A 1973 housing competition design by Andrews Downie & Kelly with Pierre Lagesse for Royal Mint Square (London)

Note that within the types of housing listed above there is a virtual absence of built-in furniture. Room function is usually defined by items of moveable furniture and storage units. Conclusions from our research were that adaptable housing should be built with an increase in prevailing net areas of up to 10% (i.e. about 6% cost increase), to provide the 'slack' necessary to accommodate real variety of use. Simple plan forms, regular structure and external walling would also contribute to value and resilience against obsolescence.

These findings embody an implicit criticism of functional modernist planning. We argued for an eclectic concept of adaptability that returns to first principles, that avoids stereotyping occupants. We were inspired by a notion of eclecticism borrowed from Diderot, that had been brilliantly deployed by Peter Collins (Collins, 1965). Our slogan became occupant choice through ambiguity, with minimum predetermination of patterns of use. Layouts seek to allow as wide a range of interpretations as possible; there is a minimum of design features that would inhibit particular patterns of use. Decisions about how to live in the space should remain with the occupants.

Since the 1970s there has been continuing interest in adaptable housing as space and amenity continue to be constrained, aggravated by abandonment of space standards and deregulation of construction generally. But unfortunately, the remorseless quest for lowest cost solutions that is baked into neo-liberal economics makes the achievement of adaptable housing even harder today than it was back in the 1970s. Several authors have recognised the contradictions between 'efficient design' and the looseness of fit that makes buildings better able to remain effective over longer periods of time (Schmidt III et al., 2016; Saarimaa and Pelsmakers, 2020). John Habraken and Stuart Brand with their visions for 'Open Building' and flexible building had been making a similar point for decades.

The pressing imperatives of climate change may at last make adaptable forms of housing the economically obvious choice. They are exemplars of sustainability. Resource scarcity and the cost of energy embodied in construction already frequently make re-development less attractive than adaptation and re-use. At least these matters are being taken more seriously by politicians than they ever were. New construction with longer life and looser fit, particularly in urban areas, will become increasingly viable. And that is before the imposition by governments of serious penalties and incentives that are bound to come, needed to goad the very conservative materials and construction sector to wake up to the new reality. Access to capital, too, is likely to become more contingent on life cycle costing and resource efficiency. Hopefully sustainability will soon become more than just a fuzzy slogan, as successive government reports have insisted it needs to be (Pearce, 2003; Stern, 2007).

The editors of the Buildings and Cities forthcoming special issue on Housing Adaptability rightly highlight different types of adaptability - environmental, spatial, social, multi-user - each of which should play a part in achieving the genuine sustainability that will be fundamental to our survival on the planet.

References

Collins, Peter. (1965). Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture. London: Faber & Faber.

Pearce, David. (2003). The Social and Economic Value of Construction. London: Construction Industry Research and Innovation Strategy Panel, nCRISP.

Rabeneck, A., Sheppard, D. & Town, P. (1973). Housing Flexibility, Architectural Design, 43 (11), 698-711, 716-727.

Rabeneck, A., Sheppard, D. & Town, P. (1974). Housing Flexibility/Adaptability? Architectural Design, 44 (2), 76-91.

Saarimaa, S. & Pelsmakers, S. (2020). Better living environment today, more adaptable tomorrow? comparative analysis of Finnish apartment buildings and their adaptable scenarios. Yhdyskuntasuunnittelu, 58 (2), 33-58. https://doi.org/10.33357/ys.89676

Schmidt III, R. & Austin, S. (2016). Adaptable Architecture: Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN: 978-0415522571

Stern, N. (2007). The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stone, P.A. (1970). Urban Development in Britain, Standards, Costs and Resources 1964-2004. NIESR, Cambridge University Press.

Till, J. & Schneider, T. (2007). Flexible Housing. London: Architectural Press. ISBN: 978-0750682022

Note

[1] As Building Systems Development (BSD), a consultancy, our research was sponsored by Strafor+Hauserman, the French partners of American E. F. Hauserman, steel partition manufacturers, who operated a sophisticated metalwork factory in Strasbourg, making furniture and partitions for offices (they later made Steelcase furniture for Europe). Hauserman had been the successful partition suppliers for the SCSD California school building system managed by our principal, architect Ezra Ehrenkrantz. We, BSD London, had discussed with Strafor a possible residential market for their partition products, and they agreed to pay for the research.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Acceptability of sufficiency consumption policies by Finnish households

E Nuorivaara & S Ahvenharju

Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse

É Savoie, J P Sapinski & A-M Laroche

Cooler streets for a cycleable city: assessing policy alignment

C Tang & J Bush

Understanding the embodied carbon credentials of modern methods of construction

R O'Hegarty, A McCarthy, J O'Hagan, T Thanapornpakornsin, S Raffoul & O Kinnane

The changing typology of urban apartment buildings in Aurinkolahti

S Meriläinen & A Tervo

Embodied climate impacts in urban development: a neighbourhood case study

S Sjökvist, N Francart, M Balouktsi & H Birgisdottir

Environmental effects of urban wind energy harvesting: a review

I Tsionas, M laguno-Munitxa & A Stephan

Office environment and employee differences by company health management certification

S Arata, M Sugiuchi, T Ikaga, Y Shiraishi, T Hayashi, S Ando & S Kawakubo

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Culture change in the UK construction industry: an anthropological perspective

I Tellam

Are people willing to share living space? Household preferences in Finland

E Ruokamo, E Kylkilahti, M Lettenmeier & A Toppinen

Towards urban LCA: examining densification alternatives for a residential neighbourhood

M Moisio, E Salmio, T Kaasalainen, S Huuhka, A Räsänen, J Lahdensivu, M Leppänen & P Kuula

A population-level framework to estimate unequal exposure to indoor heat and air pollution

R Cole, C H Simpson, L Ferguson, P Symonds, J Taylor, C Heaviside, P Murage, H L Macintyre, S Hajat, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Finnish glazed balconies: residents' experience, wellbeing and use

L Jegard, R Castaño-Rosa, S Kilpeläinen & S Pelsmakers

Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis

C C Nwagwu, S Akin & E G Hertwich

Mapping municipal land policies: applications of flexible zoning for densification

V Götze, J-D Gerber & M Jehling

Energy sufficiency and recognition justice: a study of household consumption

A Guilbert

Linking housing, socio-demographic, environmental and mental health data at scale

P Symonds, C H Simpson, G Petrou, L Ferguson, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Measuring health inequities due to housing characteristics

K Govertsen & M Kane

Provide or prevent? Exploring sufficiency imaginaries within Danish systems of provision

L K Aagaard & T H Christensen

Imagining sufficiency through collective changes as satisfiers

O Moynat & M Sahakian

US urban land-use reform: a strategy for energy sufficiency

Z M Subin, J Lombardi, R Muralidharan, J Korn, J Malik, T Pullen, M Wei & T Hong

Mapping supply chains for energy retrofit

F Wade & Y Han

Operationalising building-related energy sufficiency measures in SMEs

I Fouiteh, J D Cabrera Santelices, A Susini & M K Patel

Promoting neighbourhood sharing: infrastructures of convenience and community

A Huber, H Heinrichs & M Jaeger-Erben

New insights into thermal comfort sufficiency in dwellings

G van Moeseke, D de Grave, A Anciaux, J Sobczak & G Wallenborn

'Rightsize': a housing design game for spatial and energy sufficiency

P Graham, P Nourian, E Warwick & M Gath-Morad

Implementing housing policies for a sufficient lifestyle

M Bagheri, L Roth, L Siebke, C Rohde & H-J Linke

The jobs of climate adaptation

T Denham, L Rickards & O Ajulo

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Decolonising Cities: The Role of Street Naming

During colonialisation, street names were drawn from historical and societal contexts of the colonisers. Street nomenclature deployed by colonial administrators has a role in legitimising historical narratives and decentring local languages, cultures and heritage. Buyana Kareem examines street renaming as an important element of decolonisation.

Integrating Nature into Cities

Increasing vegetation and green and blue spaces in cities can support both climate change mitigation and adaptation goals, while also enhancing biodiversity and ecological health. Maibritt Pedersen Zari (Auckland University of Technology) explains why nature-based solutions (NbS) must be a vital part of urban planning and design.