www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/integrating-feedback.html

Integrating Feedback into Research and Practice

Challenges ahead: collecting, managing, integrating and sharing comprehensible findings on actual performance from cradle to grave

Adrian Leaman (Usable Buildings) reflects on the Probe research project, drawing lessons for the architectural and building research challenges ahead. He advocates practice-based, real-world, case-study research with a positive commitment of all concerned to qualitative improvement for the public and private good using a more engaged professional support system.

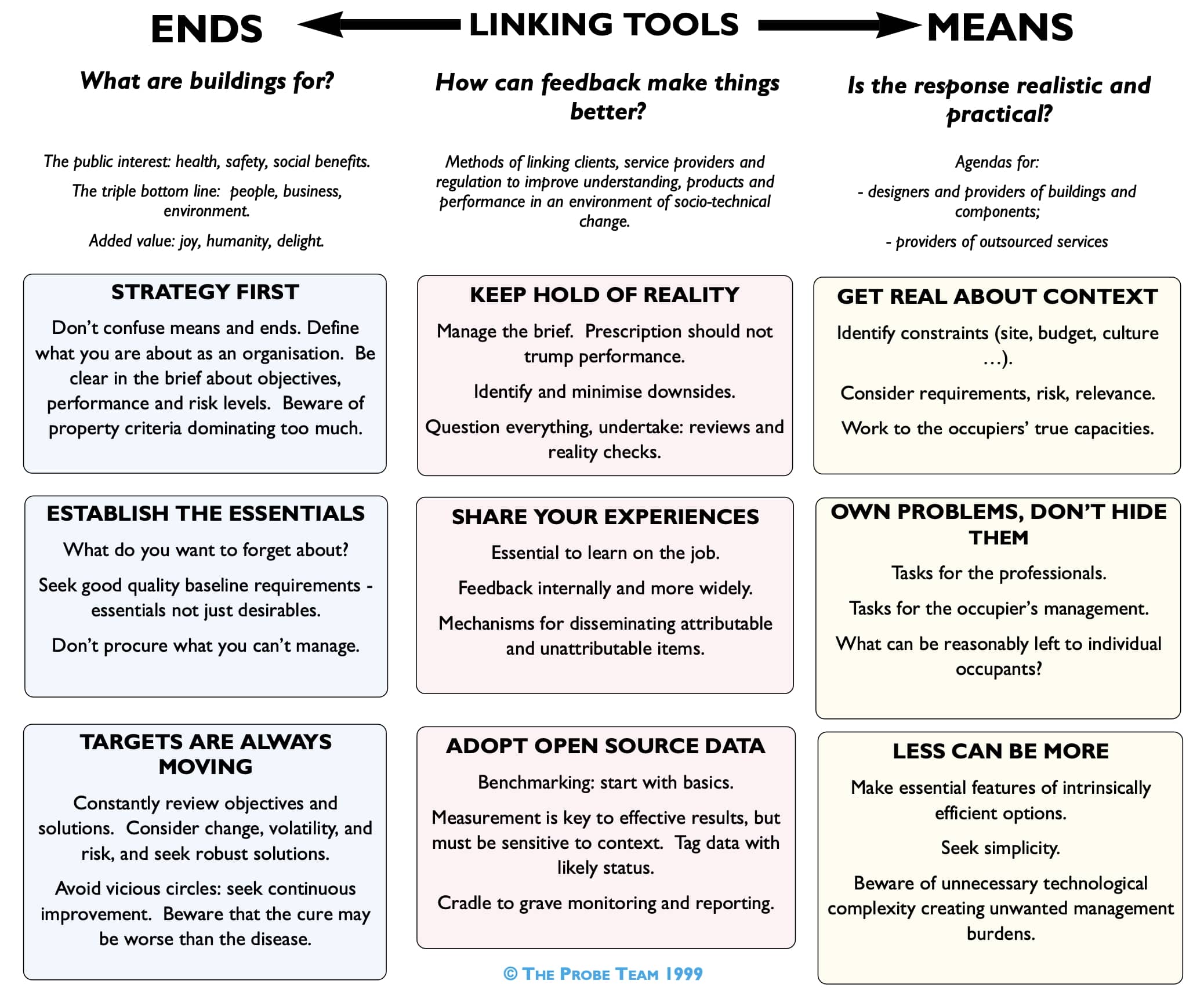

The multi-disciplinary project that gave flesh to this approach was Probe - 'Post-Occupancy Review of Buildings and their Engineering" (nowadays we would substitute 'Environment' for "Engineering'). The project outputs are archived in the Probe section of usablebuildings.co.uk . There were twenty-three building studies in all, and five final report papers. One of these, Final Report 4, was subtitled "Strategic Conclusions: Get Real About Building Performance". From this comes a summary diagram of "pointers" for the future, which we called 'the Probe Nine' (Figure 1). We said in 1999:

'It is vital to integrate space, time and performance issues, to design for usability and manageability, and to know who owns which problems. Often one finds too much concentration on the means (the building) than on the benefits it will bring to the occupiers; and what it will demand of them. Consequently, there can be a loss of grip on overall mission. Expectations of buildings by clients, designers and occupants can easily be unrealistic, with unresolved problems "parked" in the areas of greatest ignorance. Examples are enthusiasm about the promises of new technology, but not assessing possible downside risks; relying too much on management without considering the effort and costs involved; and not addressing possible needs for fine-tune once a building is occupied.'

Looking at Figure 1, on the left are the ends, where the commissioning client and user client usually stand. On the right are the means: the buildings and the designers, contractors, suppliers and others who provide and service them. In design situations, often the spotlight falls on the building as an end in itself, rather than the means to the occupier's ends. In the middle are linking tools based on feedback, helping to build bridges between the ends and the means, the demand-side and the supply-side.

Where is this leading? The key is how feedback works, and how it is professionally managed. This is the territory of virtuous and vicious circles, chronic and acute performance problems, reputational damage, hiding the bad news, shooting the messenger. Probe was a case in point. We included an opportunity for design teams to respond to the study findings, and published these alongside our own building assessments. That way we could talk about faults openly, not just successes. The design team still had some control over the narrative, but we did not shirk discussion of perceived failures. A viable and useful knowledge system has processes which link means to ends via performance feedback protocols. This is second-nature to many risk- averse professions and industries, like medicine or transportation. The reason why there is so much dissonance in architecture and construction - between academia and design practice, professional skill sets, historic and modern building practice and research funding, amongst several more - is the embedded reticence towards formal routine feedback.

This means academia needs to work with industry to produce more relevant research outputs devoid of unnecessary jargon, such as the briefing notes introduced by Buildings & Cities, rather than expecting research articles are all that is needed. The same applies to statistical tables, diagrams and architectural plans. Communicating in different mediums can be challenging for authors and researchers, but essential if a better grip on ends, needs, purpose, strategy and the other features that clients need to consider in a building brief. Academia needs to be much more tolerant of real-world research outside the laboratory and more skeptical of over-optimism with computer modelling and big data.

Downwind of Probe we were well aware that 'Making feedback routine' was vital for progress. Many of the initiatives we considered, encouraged or attempted are described in Bordass et al. (2004):

'After many false dawns, it now seems possible that feedback and post-occupancy evaluation will begin to become more routine - promising better, nicer, more productive, more cost-effective and more sustainable buildings which are better suited to the needs of their users. It will be a long haul, but clients, designers and government are becoming more interested in building performance and some are already requiring or offering aftercare services.'

We created the Usable Buildings Trust, hoping that its impetus would lead to new social institutions devoted to promoting research, training and education. The rump of that initiative is the usablebuildings.co.uk website. This hosts building case studies which can safely be placed in the public domain, together with other Probe-inspired projects like Soft Landings and New Professionalism, plus presentations and support material. The timeline (Usable Buildings n.d.) records where we went with this.

Realistically, progress has been tangible, but far slower than we would have expected or liked. In the middle of it all on 14 June 2017 came the tragic circumstances of the Grenfell Tower fire. We now have a better understanding of the venality and greed of the main perpetrators (Grenfell Tower Inquiry 2024). But even with the Inquiry's forensic investigations, extensive recommendations and the benefit of hindsight, we can still see that there is far too much focus on a self-serving construction industry.

Taking a needs-focused social and environmental view might still have meant that tower blocks would be built in the first place, but only as long as there were management resources secured and in place to run them effectively. What you certainly don't do is to add unmanageable complexity to an already fragile system in the name of "improvement" thereby multiplying the chances that things will go wrong.

On this basis it is obvious where we need to go in the future. Far more effort needs to go into areas that have normally been the province of applied social science. These include:

- practice-based knowledge management systems, tailored to the needs and resources of practices of all types and sizes

- simpler and consistently reliable methods for performance data gathering in the field

- new protocols for non-compromising information sharing between professionals and practices who would normally compete with each other

- public interest not-for-profit institution building along the lines pioneered by Michael Young and carried forward by the Young Foundation (2024).

- more emphasis on risk management together with understanding the processes of improvement and deterioration in both the historic building stock and modern construction

- a targeted approach to building briefing, with frameworks that encourage cradle-to-grave monitoring as incorporated in, for example, Soft Landings.

As for Probe, we look back more at lost opportunities than successes. At the time, further funding was denied us because the work could not be framed as 'innovative'. We were suggesting perhaps two new Probe studies annually, carried out by the ad hoc multi-professional team working without the inflated administrative and cost overheads of the university sector. At a conservative estimate that might have contributed a further 50 case studies, together with the designers' responses to the findings.

Making feedback routine would have been the simplest, fastest and most cost-effective way of repairing the systemic breakdown that has manifest its worst features in a mendacious building industry. However, momentum may still be there for that to happen. The lessons from Grenfell yet again show why feedback research is vital to ensure that buildings are designed, built and operated robustly and with low risk. Such knowledge is needed by regulators, practitioners and society. It's time for research funders to reframe their notions of "innovation" to include a feedback research programme.

References

Bordass W., Derbyshire A., Eley J. & Leaman A. (2004). Beyond Probe: Making Feedback Routine. Conference: Closing the Loop: Post-Occupancy Evaluation: the Next Steps, 29 April - 2 May 2004, Windsor, UK. https://www.usablebuildings.co.uk/UsableBuildings/Unprotected/BeyondProbe.pdf

Grenfell Tower Inquiry. (2024). Phase 2 report, September 2004, London: House of Commons. https://www.grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk/phase-2-report

Leaman A., Bordass W. & Ruyssevelt P. (1999). Probe Final Report 4: Strategic Conclusions: Get Real About Building Performance. https://www.usablebuildings.co.uk/UsableBuildings/Unprotected/Probe/ProbePDFs/SR4.pdf

Usable Buildings. (n.d.). Probe archive. https://www.usablebuildings.co.uk/UsableBuildings/ProbeListAll.html

Usable Buildings. (n.d.). Usable Buildings Timeline. https://www.usablebuildings.co.uk/UsableBuildings/Timeline.html

Young Foundation. (2024). Shaping a fairer future. https://www.youngfoundation.org

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Reimagining circularity: actions for optimising the use of existing buildings

R Lundgren, R Kyrö, S Toivonen & L Tähtinen

Effective interdisciplinary stakeholder engagement in net zero building design

S Vakeva-Baird, F Tahmasebi, JJ Williams & D Mumovic

Metrics for building component disassembly potential: a practical framework

H Järvelä, A Lehto, T Pirilä & M Kuittinen

The unfitness of dwellings: why spatial and conceptual boundaries matter

E Nisonen, D Milián Bernal & S Pelsmakers

Environmental variables and air quality: implications for planning and public health

H Itzhak-Ben-Shalom, T Saroglou, V Multanen, A Vanunu, A Karnieli, D Katoshevski, N Davidovitch & I A Meir

Exploring diverse drivers behind hybrid heating solutions

S Kilpeläinen, S Pelsmakers, R Castaño-Rosa & M-S Miettinen

Urban rooms and the expanded ecology of urban living labs

E Akbil & C Butterworth

Living with extreme heat: perceptions and experiences

L King & C Demski

A systemic decision-making model for energy retrofits

C Schünemann, M Dshemuchadse & S Scherbaum

Modelling site-specific outdoor temperature for buildings in urban environments

K Cebrat, J Narożny, M Baborska-Narożny & M Smektała

Understanding shading through home-use experience, measurement and modelling

M Baborska-Narożny, K Bandurski, & M Grudzińska

Building performance simulation for sensemaking in architectural pedagogy

M Bohm

Beyond the building: governance challenges in social housing retrofit

H Charles

Heat stress in social housing districts: tree cover–built form interaction

C Lopez-Ordoñez, E Garcia-Nevado, H Coch & M Morganti

An observational analysis of shade-related pedestrian activity

M Levenson, D Pearlmutter & O Aleksandrowicz

Learning to sail a building: a people-first approach to retrofit

B Bordass, R Pender, K Steele & A Graham

Market transformations: gas conversion as a blueprint for net zero retrofit

A Gillich

Resistance against zero-emission neighbourhood infrastructuring: key lessons from Norway

T Berker & R Woods

Megatrends and weak signals shaping future real estate

S Toivonen

A strategic niche management framework to scale deep energy retrofits

T H King & M Jemtrud

Generative AI: reconfiguring supervision and doctoral research

P Boyd & D Harding

Exploring interactions between shading and view using visual difference prediction

S Wasilewski & M Andersen

How urban green infrastructure contributes to carbon neutrality [briefing note]

R Hautamäki, L Kulmala, M Ariluoma & L Järvi

Implementing and operating net zero buildings in South Africa

R Terblanche, C May & J Steward

Quantifying inter-dwelling air exchanges during fan pressurisation tests

D Glew, F Thomas, D Miles-Shenton & J Parker

Western Asian and Northern African residential building stocks: archetype analysis

S Akin, A Eghbali, C Nwagwu & E Hertwich

Latest Commentaries

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.

Lessons from Disaster Recovery: Build Better Before

Mary C. Comerio (University of California, Berkeley) explains why disaster recovery must begin well before a disaster occurs. The goal is to reduce the potential for damage beforehand by making housing delivery (e.g. capabilities and the physical, technical and institutional infrastructures) both more resilient and more capable of building back after disasters.