www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/lessons-swiss-impulse.html

Lessons from the Swiss Impulse Programme

What works: this Swiss programme shows how a long-term, consistent approach by government and other stakeholders created a successful transition for construction SMEs. It could be adapted for a low-carbon transition.

The former Swiss 'Impulse programme' was a successful response to the 1970s energy crisis. It provides important lessons for today's climate emergency about what governments, industry and academia can do to create a successful transition within the construction industry. Niklaus Kohler and Kurt Meier (both former members of the Construction and Energy Impulse programmes) reflect on key lessons for today about its implementation and how to sustain change over the short and long term.

The long cycles

Two new situations occurred in the 1970s. The first was the end of the long economic boom which began after the end of World War 2. This was interpreted as a 'Kondratiev' wave - a long-term intergenerational economic cycle (lasting approximately 40 years) of alternating intervals of high sectoral growth resulting from technological innovation and intervals of relatively slow growth. The second was the 'energy crisis' which ended low energy prices. This impacted on oil consumption and the increasing affordability of material consumer goods, particularly automobiles.

Such long growth periods had not existed before and their importance was not understood. Their visible effects were the increase of urbanisation, infrastructure and pollution. The political reaction to these changes were in general large public demand-side (investment) programs. The building and infrastructure stock changed, their renovation cycle was shorter and more frequent. It became clear that the maintenance of the building and infrastructure was a long-term task. The term 'built environment' encompassed a number of different economic and social phenomena. Renovation became the norm and the share of renovation activities was approaching 50%.

The 'Construction and Energy' Impulse programme

The Impulse programmes were initiated by the Swiss federal government in close cooperation with Swiss professional organizations, construction firms, education institutions and research institutes. The overarching aim of these programmes was economic: to stimulate innovation activities, maintain innovative strength and secure the long-term competitiveness of small to medium-sized companies. The programs were initially aimed at job creation, but the objective was soon enlarged to embrace to qualitative improvement of the building stock and energy savings. The focus shifted from short-term interventions (i.e. maintenance) to longer-term stewardship. This required a shift in thinking, new competences and practices, along with a comprehensive set of coordinated measures at different levels and for different professions / vocations. The 'Construction and Energy' Impulse programme was composed of 6 programs over 18 years (1978 to 1996).

Knowledge gaps

Prior to 1978, existing professional education in Switzerland was nearly exclusively based on the realization of new construction. The knowhow for maintenance and operation were neglected. There were important and diverse knowledge gaps among many stakeholders: owners, users, specialists, authorities, planners, contractors and workers

The Impulse programs soon recognised and addressed the many knowledge gaps amongst stakeholders for the maintenance of the built environment. As a result, the focus shifted to qualitatively oriented economic growth, by creating the optimal conditions for the long-term development of the settlement structure and the infrastructure. The new perspective was the life cycle of the built environment.

The first Impulse program (1978-1982 ) developed a specific method for retrofitting existing buildings. It addressed planners, architects and engineers and developed a new method to calculate energy consumption, ways to improve the building envelope and practices to improve the heating and hot water systems. A method for the energy efficient retrofit and operation of existing buildings was developed.

Implementation

The programme established and maintained technical and social contacts with a number of trade and professional organisations which had not been previously involved in educational programs. The programme's ambitious goals necessitated the cooperation between specialists, experts familiar with the different fields and executives of the different professional associations. The choice of the courses, their content, methods and tools were proposed by small teams of "reflective practitioners" (Schön 1983, 1987). It was necessary to find specialists with awareness of the multiple long-term aspects of the built environment including urban planners, government authorities, cultural heritage specialists. The contribution from reflective practitioners was crucial for the programme. These specialists were already very active in their organisation and they could only participate in the program in relatively short periods (and in their free time).

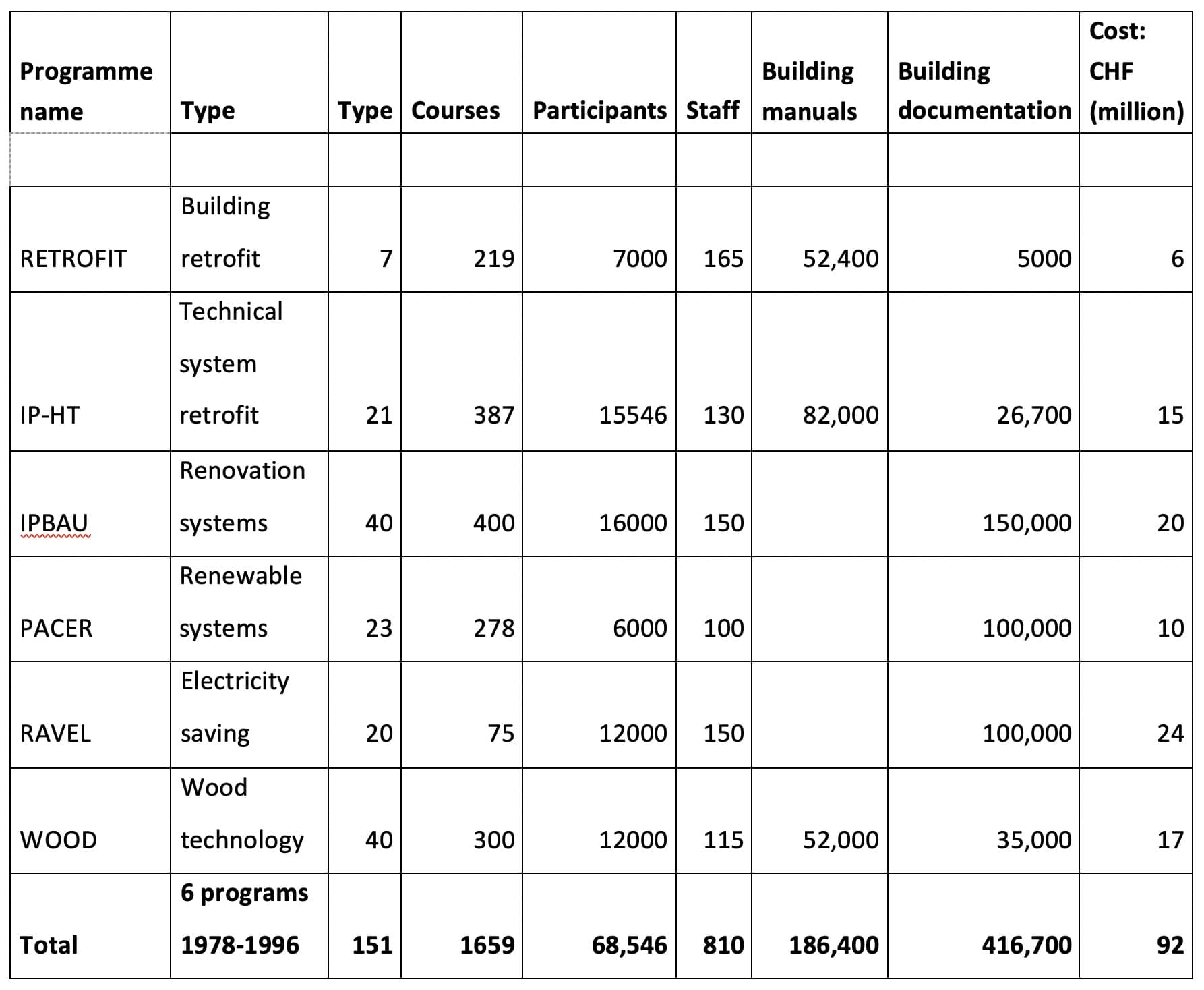

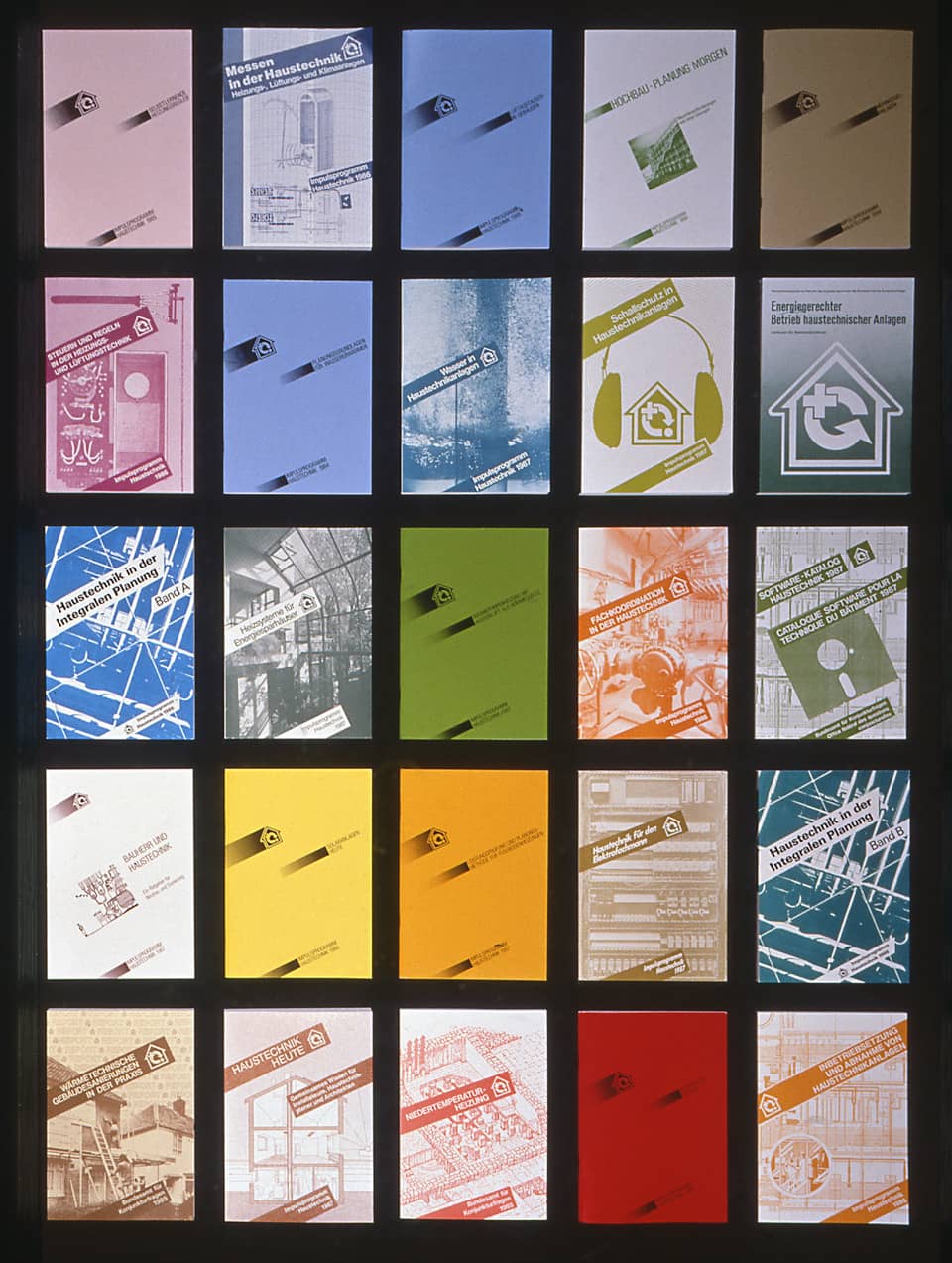

The courses were tested in a prototype course before they were implemented. The documentation was established by the team and selected specialists for the different course and languages were contacted. The programme had significant impacts. There were 151 types of courses, 1659 delivered courses, over 68,000 participants, 186,400 manuals and 416,700 documentations (see Table 1). The rapid development of the different programs in 3 languages was a complex process combining technical as well as teaching and social competences. It advanced quickly and profited from the knowledge and experience of reflective practitioners.

Governance

The governance of the programme was straightforward. The strategic and financial direction were in the remit of a committee, composed of the representatives from the participating organizations. Each of the 6 programmes had a programme director and each of the courses had a working group composed of specialists and reflective practitioners. For special tasks short time groups were created. The practical organisation of the courses (infrastructure, participation, finance) was assumed by the professional organisations.

Tools

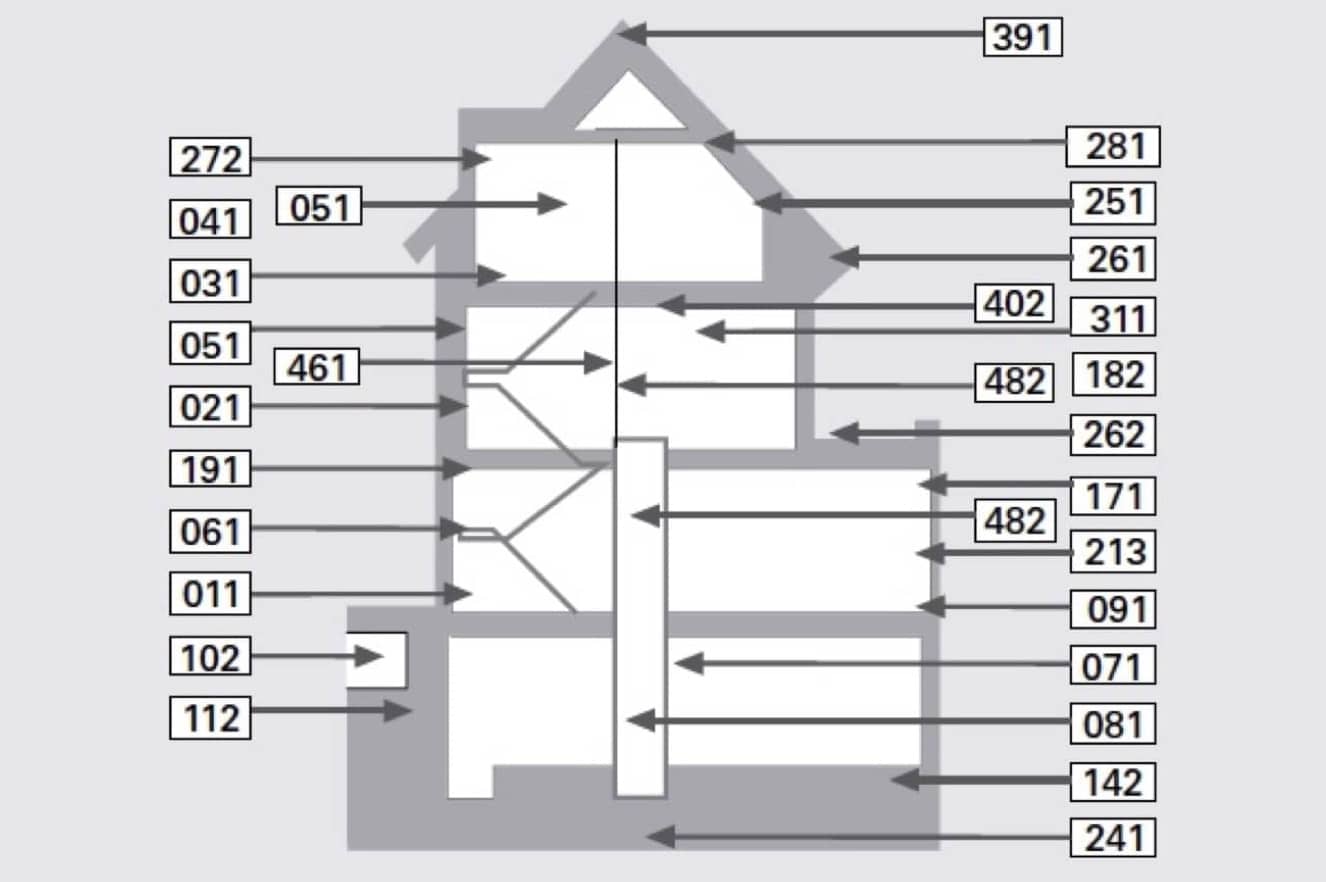

A considerable number of tools were elaborated for the courses and could be adapted and used by interested groups and professionals. For example, the first Impulse programme developed a specific method for the retrofit of existing buildings called 'Grobanalyse'. It developed a new method for architects and engineers to describe the retrofit object (e.g. building) and to evaluate the state of the 50 building elements. Based on the same data it calculated the cost (and later the energy savings) of the retrofit. The diagnostic process lasted 1 day and the result was a project brief which proposed different levels of retrofit. The costs were kept low: approximately the fee for one day's work of a specialist. The client received a report with different interventions (degree, immediate or later), scope (fabric, heating and hot water systems, etc), probable cost, and probable energy consumption. A complete and validated method for the energy efficient operation of existing buildings was also developed. The method was used for the documentation, analyses and the basis for the long-term management of different building stocks. and documentation of larger buildings stocks.

Documentation

The (paper) documents were established by the course working committee documentation, the models and the digital tools were established by the teaching teams. The documents were translated and edited in 3 languages: German, French, Italian.

Results

The programme was successful for several aspects of retrofitting different types of buildings and building stocks. The structure of the governance integrated different professional competences into a transdisciplinary approach. The governance allowed a high flexibility and adaptability during the programme. It developed new forms of knowledge transfer (models, scenarios etc.) established a consensus between professional organizations, research and development, and public education. The intervention of their 'reflective practitioners' created a high level of professional practice. The programmes produced a large number of manuals, documentations and software (in 3 languages) written by experts and relevant for immediate knowledge transfer into professional practice.

The most important drawback of the programme was the fact that it was terminated, so the information was not updated and no longer widely disseminated. The creation and conservation of professional knowledge and practices were central objectives of the program. Knowledge is always embedded within a person. So each and every generation needs to gain this knowledge. Closing a successful programme puts this in jeopardy. The end of the Construction and Energy programme is maybe another example of the "amnesia" that affects the construction industry (Markus 2001).

The idea behind the Impulse programme was the understanding of the long-term perspective - which was only partially understood in the beginning - with a short-term action which was very flexible and directly linked to professional practice of reflective practitioners.

What next?

The Swiss Impulse programme shows what can be implemented effectively and successfully. Do societies need to launch new versions of the Impulse programmes? The immediate answer could certainly be a large climate program for the built environment combining mitigation and adaptation strategies. However, this requires a long-term commitment to implement change: upskilling the workforce and creating real market transformation. Moreover, its success depends on the involvement, commitment and commitment of many diverse stakeholders.

References

Markus, T.A. (2001). Does the building industry suffer from collective amnesia? Building Research & Information, 29(6), 473-476.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D.A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the profession. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.