www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/multi-level-climate-governance.html

Multi-level Climate Governance at COP27: Enable City Actions

By Liane Thuvander (Chalmers University) and Heba A.E.E. Khalil (Cairo University)

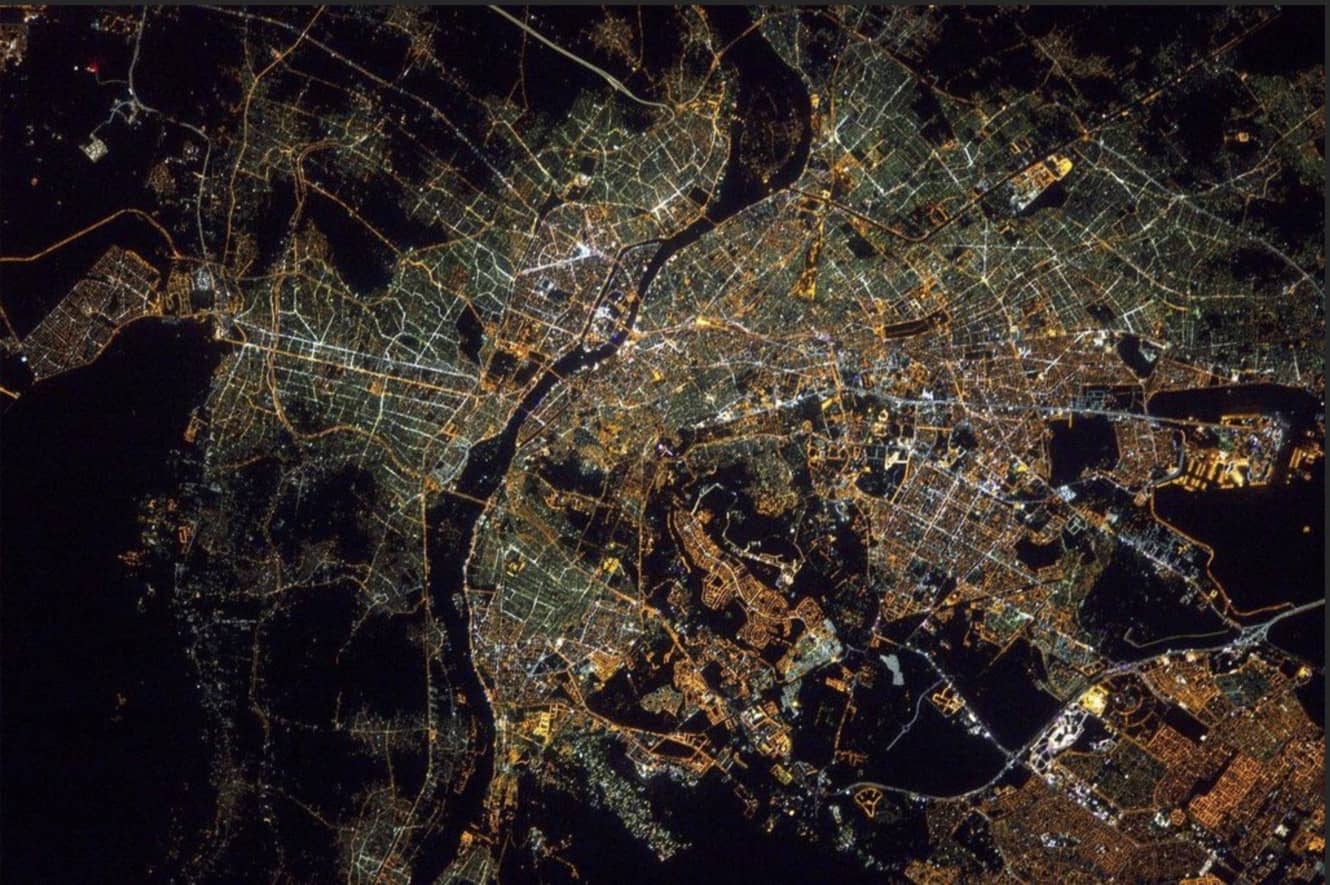

For COP27 to be a turning point in climate change action, it needs to pave the way for local projects and programs to proliferate. This may be most effectively achieved by establishing frameworks for context specific governance on multi-levels. How multi-level governance can support climate policy and what is needed to implement it effectively is shown. Two very different contexts demonstrate how climate governance acts at a city scale: Gothenburg, Sweden and Giza, Egypt.

Sweden: central government can enable cities

Sweden has a long tradition working with environmental and climate issues. By 1999 the Swedish Parliament had already adopted 15 environmental objectives. Two of them, "reduced climate impact" and "a good built environment", specifically address climate impact and cities. In 2017, a new climate policy framework was adopted providing a long-term signal to the market and other actors that Sweden is to achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2045 and to have negative net emissions after this.Despite these ambitious goals, the current monitoring indicates that Sweden is struggling to meet its target, illustrating the implementation gap.

Sweden also has national energy policy goals regarding renewables and energy efficiency, energy and carbon dioxide taxes, and promotes communication of policy instruments via national agencies. For instance, Boverket (Sweden's National Board of Housing, Building and Planning) supports the national goal of "a good built environment" by targeting efficient energy systems integrated with environmentally friendly and accessible public transport systems. A complementary policy adopted in 2018, "Designed Living Environments" identified architecture as one instrument (amongst others) to tackle climate change. Since January 2022, Boverket has required new buildings to provide declarations on their climate impacts. Additionally, regional and sector level strategies exist to create independence from fossil fuels and promote electrification. These strategies collectively target a broad range of stakeholders and include systems wider than city boundaries. Overall, the landscape of national, regional, and sectoral climate frameworks is comprehensive, but they give little guidance on how to translate commitments into action on the city level.

Local actions: the example of Gothenburg

Swedish cities are actively engaged and play a crucial role in the process of climate and energy transition, connecting local developments via urban planning to national frameworks and goals. In this perspective, the City of Gothenburg developed an Environmental and Climate Programme 2021-2030 based on goals for nature, climate, and people; to boost biodiversity, a near zero carbon footprint and a healthy living environment. The programme does not yet contain goals regarding climate change adaptation.

Gothenburg participates in theEU Mission for 100 climate-neutral cities by 2030, and has signed the Climate City Contract 2030, a contract between cities, government agencies and a strategic innovation programme. Beyond this, Gothenburg is also engaged in research projects with local universities and public organisations to co-produce knowledge, including the Centre for Sustainable Urban Futures. . The city has launched a research council to support and evaluate its climate policy. Finally, the city has designated responsible actors for implementation of their strategies. Thus, the city has frameworks for actions, lots of commitment and activities, and good knowledge of climate action implementation. But this does not necessarily lead to success, per se; additional efforts are needed.

A recent study of Gothenburg's Energy Plan (Maiullari et al. 2022) revealed that a high level of uncertainty and diversity among actors makes it difficult to identify common or shared pathways to follow. In the case of the energy plan, challenges regarding the coordination between different domains especially in energy and urban planning; the adaptation of systemic thinking to benefit the community rather than single stakes or stakeholders; and the lack of proper communication tools for the decision-makers to facilitate multi-domain processes.

In the Swedish case, comprehensive and mutually dependent frameworks and instruments for climate change action are in place, allowing multi-level action. Initial appraisals suggest that local implementation would benefit from exploratory instruments that consider a multiplicity of domains and actors' perspectives (public, private, non-state). This would help inform local decisions in the climate and energy transition context, as well as help prioritise strategies and assess the consequences of their implementation. Another aspect, not discussed here, is the question of by whom, and on what system level, the (financial) burdens should be placed?

Egypt: central government context

In the Global South, climate actions can come second to pressing development priorities. In a centralised, middle-income country as Egypt, climate action faces several structural challenges and barriers. One of the first barriers is to identify cities as a priority action area in climate action. Moreover, providing autonomy to cities in terms of actions and budgets is fundamental to realising actions and effective metropolitan governance. Doing so will facilitate coordinated actions between municipalities, as in the case of Greater Cairo Region (GCR).

The newly announced Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) incorporated both mitigation and adaptation measures and encompass cities as a focal sector (Egypt 2022), which provides an overall political and institutional support for local level actions. The NDC document highlights current challenges and actions taken since the 2015 Intended Nationaly Determined Contributions (INDCs) which previously focussed only on national scale supply side interventions with limited local level actions. For instance, energy efficiency measures for low carbon transport, solid waste management and green finance were all implemented by the central government.

For buildings and urban cities, the new NDCs now identify mitigation targets for renewable energy and energy efficiency, green buildings, increasing green spaces, solar street lighting and even incorporate a National Active Mobility Strategy, to encourage citizens to walk and cycle. Regarding adaptation targets, in addition to the existing focus on water resources and irrigation; agriculture, and coastal zones that were previously part of the INDCs now a new sector for urban development and tourism to address climate resilience of touristic sites, road networks and endangered sites has been added. Thus, there is a shift towards local actions advocated by NDCs and which can be supported by a package of related laws, regulations and monitoring apparatus.

Giza's actions

Analysis of the Giza Climate Change Strategy Framework, suggested Giza's metropolitan governance faced challenges around knowledge, awareness, resources and capacity to advocate for and develop local climate change strategies and actions. These challenges limit the ability of Giza's metropolitan governance system to coordinate climate actions with other parts of GCR. Through the development of the Giza Climate Change Strategy Framework, five main strategic policies were identified: conserving resources; preserving the governorate's assets from climate change impacts; improving infrastructure and services to adapt to climate change; achieving low-emission development; and protecting citizens from the health impacts of climate change (Giza Governorate 2018).

Several prerequisites for effective climate action were identified that would fit similar cities within similar governance contexts. These consist of two groups: capacities and resources as prerequisites for governance framework, and inclusive cooperation. The capacities and resources requirements focus on raising climate change awareness, enabling local workable knowledge, providing technical and financial support from higher levels, implementing local climate impacts studies and raising capacities of local municipality employees. Inclusive cooperation focuses on increasing prioritisation of environmental welfare, creating co-benefits with development priorities, granting higher levels of autonomy, activating means of accountability and monitoring systems, creating long term climate change visions for all settlements, deploying effective and equitable public engagement mechanisms, coordination with other levels of the government (vertically and horizontally), and mainstreaming climate change into sensitive sectors like health and education(Eissa & Khalil 2022). Hence, it is vital to consider whether these prerequisites exist before deploying any climate strategies or plans to ensure applicability of actions.

Lessons for COP27

Overall, the Global North climate policies and strategies favour mitigation measures and focus on technical solutions or changes in habits. However, increasingly, the Global North is suffering from the impacts of climate change through heat waves and flooding for example. Thus, cities' climate strategies need to combine mitigation measures with adaptation measures and resilience actions.

Adaptation is already an important issue for the cities in the Global South as a result of increased vulnerabilities. Many climate actions by cities fall under mitigation rather than adaptation, often as a direct response to available international funds and initiatives. The latest IPCC report calls for integration of mitigation and adaptation agendas in all cities across the world. Climate action projects need to be mainstreamed and incorporated within current urban development policies not seen as separate activities.

All actions require relevant governance structures. As the examples from Sweden and Egypt show, there is no single solution. Multi-level governance offers an interlinked but open framework and enables action across different levels and organisations. It is crucial to pay attention to the context and how such a governance structure can perform effectively. Action at city level is central and many cities have capabilities to act. Resilient structures are needed in terms of capacity building and through broad stakeholder engagement and resources for implementation. Even within more centralised structures, a level of autonomy and partnership with other non-governmental stakeholders should be promoted and supported to ensure realisable actions at the local level. National leaders should consider this as they engage with the COP27 negotiations.

We want young people to perceive the future positively and not with anxiety. COP27 needs to become a game changer realising the vision to move from negotiations and planning to implementation. This means actions at-scale and on the ground, translating agreements and pledges to projects and programs on the city level that make a real difference.

References

City of Gothenburg, Environment and Climate Program.

Egypt. (2022). Egypt's First Updated Nationally Determined Contributions. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/documents/522817

Eissa, Y. & Khalil, H. A. E. E. (2022). Urban climate change governance within centralised governments: a case study of Giza, Egypt. Urban Forum, 33, 197-221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-021-09441-9

Giza Governorate. (2018). Towards a Climate Change Strategy in Giza Governorate Framework Document. Giza Governorate.

Maiullari, D., Palm, A., Wallbaum, H., Thuvander, L. (2022). Pathways towards carbon neutrality: a participatory analysis of Gothenburg's energy plan. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1085, 012041.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Acceptability of sufficiency consumption policies by Finnish households

E Nuorivaara & S Ahvenharju

Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse

É Savoie, J P Sapinski & A-M Laroche

Cooler streets for a cycleable city: assessing policy alignment

C Tang & J Bush

Understanding the embodied carbon credentials of modern methods of construction

R O'Hegarty, A McCarthy, J O'Hagan, T Thanapornpakornsin, S Raffoul & O Kinnane

The changing typology of urban apartment buildings in Aurinkolahti

S Meriläinen & A Tervo

Embodied climate impacts in urban development: a neighbourhood case study

S Sjökvist, N Francart, M Balouktsi & H Birgisdottir

Environmental effects of urban wind energy harvesting: a review

I Tsionas, M laguno-Munitxa & A Stephan

Office environment and employee differences by company health management certification

S Arata, M Sugiuchi, T Ikaga, Y Shiraishi, T Hayashi, S Ando & S Kawakubo

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Culture change in the UK construction industry: an anthropological perspective

I Tellam

Are people willing to share living space? Household preferences in Finland

E Ruokamo, E Kylkilahti, M Lettenmeier & A Toppinen

Towards urban LCA: examining densification alternatives for a residential neighbourhood

M Moisio, E Salmio, T Kaasalainen, S Huuhka, A Räsänen, J Lahdensivu, M Leppänen & P Kuula

A population-level framework to estimate unequal exposure to indoor heat and air pollution

R Cole, C H Simpson, L Ferguson, P Symonds, J Taylor, C Heaviside, P Murage, H L Macintyre, S Hajat, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Finnish glazed balconies: residents' experience, wellbeing and use

L Jegard, R Castaño-Rosa, S Kilpeläinen & S Pelsmakers

Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis

C C Nwagwu, S Akin & E G Hertwich

Mapping municipal land policies: applications of flexible zoning for densification

V Götze, J-D Gerber & M Jehling

Energy sufficiency and recognition justice: a study of household consumption

A Guilbert

Linking housing, socio-demographic, environmental and mental health data at scale

P Symonds, C H Simpson, G Petrou, L Ferguson, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Measuring health inequities due to housing characteristics

K Govertsen & M Kane

Provide or prevent? Exploring sufficiency imaginaries within Danish systems of provision

L K Aagaard & T H Christensen

Imagining sufficiency through collective changes as satisfiers

O Moynat & M Sahakian

US urban land-use reform: a strategy for energy sufficiency

Z M Subin, J Lombardi, R Muralidharan, J Korn, J Malik, T Pullen, M Wei & T Hong

Mapping supply chains for energy retrofit

F Wade & Y Han

Operationalising building-related energy sufficiency measures in SMEs

I Fouiteh, J D Cabrera Santelices, A Susini & M K Patel

Promoting neighbourhood sharing: infrastructures of convenience and community

A Huber, H Heinrichs & M Jaeger-Erben

New insights into thermal comfort sufficiency in dwellings

G van Moeseke, D de Grave, A Anciaux, J Sobczak & G Wallenborn

'Rightsize': a housing design game for spatial and energy sufficiency

P Graham, P Nourian, E Warwick & M Gath-Morad

Implementing housing policies for a sufficient lifestyle

M Bagheri, L Roth, L Siebke, C Rohde & H-J Linke

The jobs of climate adaptation

T Denham, L Rickards & O Ajulo

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Climate Mitigation & Carbon Budgets: Research Challenges

Thomas Lützkendorf (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology) explains how the research community has helped to change the climate change policy landscape for the construction and real estate sectors, particularly for mitigating GHG emissions. Evidence can be used to influence policy pathways and carbon budgets, and to develop detailed carbon strategies and implementation. A key challenge is to creates a stronger connection between the requirements for individual buildings and the national reduction pathways for the built environment.

Decolonising Cities: The Role of Street Naming

During colonialisation, street names were drawn from historical and societal contexts of the colonisers. Street nomenclature deployed by colonial administrators has a role in legitimising historical narratives and decentring local languages, cultures and heritage. Buyana Kareem examines street renaming as an important element of decolonisation.