www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/phronesis-epistemic-justice.html

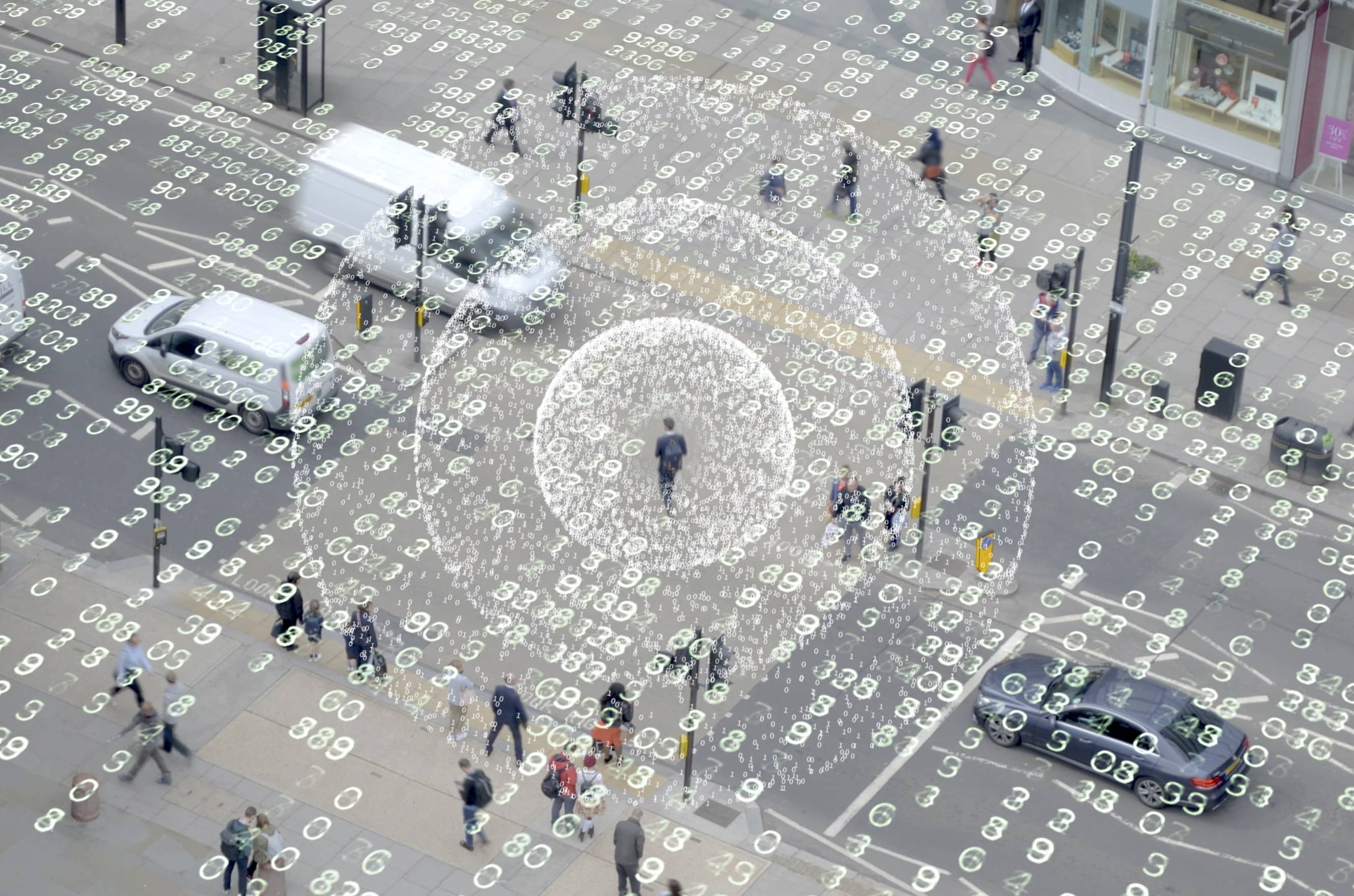

Phronesis and Epistemic Justice in Data-Driven Built Environments

Why more just and democratic ways are needed for living in smart built environments.

Miguel Valdez (Open University) comments on the contributions of the Buildings & Cities special issue Data Politics in the Built Environment. This commentary considers an additional perspective and provides an additional foundation to support more progressive data politics in the built environment. The three Aristotelian virtues of 'techne', 'episteme' and 'phronesis' and epistemic justice provide suitable lenses to critique smart city politics.

The articles in this special issue on Data Politics in the Built Environment reveal multiple dimensions of the practices, politics, and power implications of the ongoing data-driven reconfiguration of buildings and cities. Various analytical lenses, such as intersectional justice , datafication of urban flows and relations and the commoning and enclosure of data infrastructures are applied in a variety of domains and international contexts. Karvonen and Hargreaves (2023, in this issue) identify three shared themes cutting across all articles in the special issue:

- Attention to social exclusion in datafied urban systems

- The centrality of local geographies and context to processes of datafication

- The possibility of overcoming the negative aspects of datafication to achieve more progressive and emancipatory urban futures.

This commentary suggests an additional perspective cutting across the articles by considering the notions of phronesis and epistemic justice. This can provide an additional foundation to support more progressive data politics in the built environment. Drawing on Cook and Karvonen (2024), the three Aristotelian virtues of techne, episteme and phronesis are thus suggested as suitable lenses to critique smart city politics. Techne, or 'craft' refers in this context to the skills and techniques needed to enact the smart city. Questions of techne are primarily within the domain of engineering and include, for example, the design and implementation of sensing networks, platforms and data infrastructures. Karvonen and Hargreaves (2023) note that much of the work on datafication focuses on devices, technical systems and the companies behind these technologies, but such technological developments need to be contextualised and historicised.

Phronesis, or 'practical wisdom', addresses this need by offering a form of value rationality emphasising the consequences and implications of our actions in a particular context or situation. Phronesis, in the case of smart urbanism: 'serves to guide our collective ethical choices about how we design, develop and operate cities' (Flyvbjerg in Cook and Karvonen 2024:377).

The articles in this special issue suggest various approaches that take the "techne" of data infrastructures and systems as the point of departure and reach more just outcomes informed by the practical, contextual wisdom of phronesis. Implicitly, the articles place episteme (analytic and theoretical knowledge) as link or mediator between techne and phronesis. Central questions raised in the articles simultaneously address issues central to epistemic justice (Kidd and Pohlhaus 2017) such as:

- Who has voice and who doesn't?

- Are voices interacting with equal agency and power?

- In whose terms are they communicating?

- Who is being understood and who isn't (and at what cost)?

- Who is being believed?

- Who is even being acknowledged and engaged with?

The articles reveal that data captured by sensors, stored in data centres and processed algorithmically by platforms are not given, but are chosen to fit various epistemic frameworks that make sometimes invisible assumptions about what matters (and who matters) in cities. Such epistemological decisions are profoundly impactful as "…different justice frameworks use different informational bases to evaluate whether a decision, society or distribution is fair (Sen 2014). Epistemic injustice can therefore invisibly permeate all the mechanisms through which justice claims are made, through which justice is pursued and through which institutions are evaluated and held accountable (or not)" (Cook and Karvonen 2024:377).

Cook and Karvonen (2024) observed that epistemology of smart cities has a tendency to attend to those systems that can be objectively known, measured and statistically analysed while neglecting those that are not amenable to such approaches. Sharma et al. (2023, in this issue) observe that smart urban technologies are dominated by imaginaries in which users are conceptualised as 'resource men' (Strengers 2014) or equally rational 'Homo economicus' (Williams 2021). Data driven environments informed by such imaginaries predominantly serve the interests of those who, like the imagined resource man, are white, male, instrumentally rational and able-bodied. Sharma et al. thus call for alternative imaginaries of democratic smart citizenship incorporating diverse user archetypes embodying what it takes to make equal thriving and just societies through diverse social indicators including race, gender, class and income. They emphasise that narrow user-based approaches have limited transformative potential by themselves and call instead for a turn towards design justice (Costanza-Chock 2018) due to an awareness of the institutions that shape smart technologies as well as the underlying power structures and agendas. In a similar and complementary note, Mello Rose and Chang (2023, in this issue) draw attention to the limited exploratory power of data-driven approaches that focus on supposedly objective and quantifiable aspects of urban life. A pilot application making use of natural language processing applied to local press articles to understand social and cultural interactions that characterise urban life demonstrates how progress in the 'techne' of natural language processing can create new epistemic possibilities as subjective sociocultural data are made visible, enriching data-driven governance and providing decisionmakers with the means to better understand the social conditions shaping an area's urban (sociocultural) fabric.

The various perspectives developed across articles in this special issue paint a rich picture of evolving smart urbanisms facing an increasingly untenable epistemic tension: a conceptualisation of data as objective measurement of real-time urban flow is in tension with a notion of data as a politically negotiated nexus of complex relational constellations. This tension matters because when data are attended as flows, data-driven reconfigurations of the urban environment appear to be functionally the same, only more efficient. Consequently, arguments against smart city projects can be easily framed as regressive arguments against efficiency, development and sustainability. The implicit argument is that when decisions are rational participation isn't required.

The articles in this special issue illustrate how smart rationalities are not value-neutral but are often narrated as such. For instance, the platformisation of Dublin's taxi industry (White & Larsson, 2023, in this issue), when seen exclusively in terms of urban flows, would be seen as a case where the same taxis, passengers and drivers make the journeys through the same streets, with data platforms simply improving efficiencies and reducing frictions. If, on the other hand, consideration is given to the political and economic logics and the relations in which they are embedded then a transition to centralised networks and thin power structures can be observed. This affords very little separation between users and drivers and between global organisations, capitals and infrastructures. Users and drivers are thus exposed to the gaze of digital platforms that see cities as markets and humans as sources of data for consumer profiling and targeted advertising. As Sareen et al (2023, in this issue) observe, urban digitalisation is often subservient to the logics of centralisation, accumulation and surveillance capitalism, with data-hungry infrastructures enclosing access to data and spaces of decision-making while privatising the benefits of digitalisation.

Disruption of unsustainable ways of living in the built environment is necessary to cope with the ongoing environmental crisis, but responsible research on disruptive reconfigurations calls for attention to what is being disrupted, who lives with the consequences of disruption, and who gets to make decisions about it. Flyvbjerg (2004) identifies four value-rational questions that, in clarifying values, interests and power relations, provide a basis for phronetic praxis:

- Where are we going?

- Who gains and who loses, and by which mechanisms of power?

- Is the development desirable?

- What, if anything, should we do about it?

When read through a phronetic perspective, the articles in this special issue provide intriguing answers to those questions in a variety of contexts. Through the special issue, attention to the politics of the built environment suggests several practical and impactful answers to the question of what, if anything, should we do about the ongoing developments. More just and democratic ways of living in smart built environments are envisioned by means of resistance from the margins and interstices of the data platforms, as well as by attending to intersectionality and plurality and by pursuing a digital commons that is not graciously granted by elites but is negotiated or contested through collective action. Importantly, all articles reveal multiple negative and disruptive aspects of datafication but avoid a regressive rejection of smart city futures. In going beyond analysis and detached critique, the articles in this special issue open up possibilities acting otherwise, and thus develop an agenda for living better and acting more wisely in increasingly data-driven urban contexts.

References

Cook, M. & Karvonen, A. (2024). Urban planning and the knowledge politics of the smart city. Urban Studies, 61(2), 370-382. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231177688

Costanza-Chock, S. (2018). Design justice: towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3189696. Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3189696

Flyvbjerg, B. (2004). Phronetic planning research: theoretical and methodological reflections. Planning Theory & Practice, 5(3), 283-306.

Karvonen, A. & Hargreaves, T. (2023). Data politics in the built environment. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 920-926. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.394

Kidd, I.J., Medina, J. & Pohlhaus Jr, G. (eds.) (2017). The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice. Taylor & Francis.

Mello Rose, F. & Chang, J. (2023). Urban data: harnessing subjective sociocultural data from local newspapers. Buildings & Cities, 4(1), 369-385. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.300

Sen, A. (2014). Development as freedom (1999), in J.T. Roberts, A.B. Hite and N. Chorev (eds.) (2014). The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change, 525-548. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-73510-7

Sharma, N.K., Hargreaves, T. & Pallet, H. (2023). Social justice implications of smart urban technologies: an intersectional approach. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), p.315-333. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.290

Strengers, Y. (2014). Smart energy in everyday life: are you designing for resource man?. interactions, 21(4), 24-31.

White, J. & Larsson, S. (2023). Disruptive data: historicising the platformisation of Dublin's taxi industry. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 838-850. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.293

Williams, F. (2021). Social Policy: A Critical and Intersectional Analysis. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 978-1-509-54038-9

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.