www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/question-demolition.html

Time to Question Demolition!

Demolition has far-reaching consequences for people, nature and the climate. What can be done to slow its rate?

André

Thomsen (Delft University of Technology) comments on the

recent Buildings & Cities special issue 'Understanding Demolition' and explains why this phenomenon is only beginning to be understood more fully as a social and behavioural set of issues. Do we need an epidemiology of different demolition rates?

Asking the right questions?

A simple search for the term 'demolition' in e.g. Scopus and ResearchGate reveals how researchers frame this topic. Technical sources strongly dominate, with key words: demolition technique, material inventory, waste separation, recycling, sustainability. Also many real estate sources often accompany this term with: necessary, indispensable, obsolete, low quality, circular, sustainable, replace. Other disciplines, mostly sociological, are less represented. The vast majority of sources deals with housing.

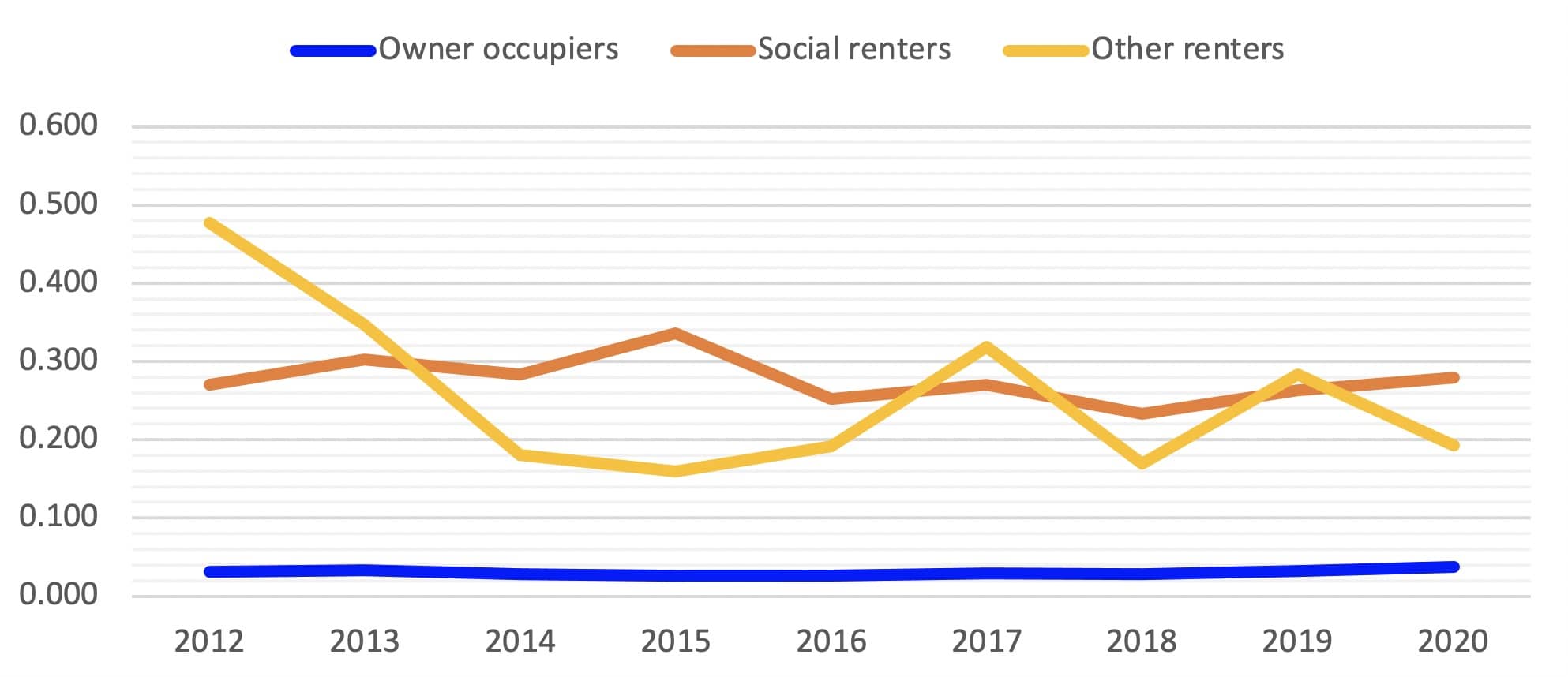

The housing stock is very heterogeneous and characteristics such as ownership and type appear to be strongly related to the demolition risk (Figure 1). This is comparable to many other European countries.

Sources: Thomsen 2023; Syswov 2023.

But the question of why a large gap occurs between rent and owner-occupied stock requires explanation. Epidemiology provides insights and explanations in other fields. For example, human mortality rates are systematically tracked and scrutinised. This has revealed that causes like low income and less education lead to earlier mortality. If large differences occur, medical researchers immediately sound the alarm and look for causes and remedies. But no similar analysis is undertaken to understand the different demolition rates for dwellings. As Dutch housing associations have started en masse demolition of older homes due to the shortage of acceptably priced building land (Thomsen 2023) there is good reason to take a closer and more critical look at the high mortality cause of homes.

For owner-occupiers, their home is typically their most valuable asset and by far the largest part of their capital, which is also visible in the low demolition figures (Thomsen et al. 2015). For property operators, their rental property is their main resource and working capital. Their options are to exploit, adapt, sell or demolish: whatever yields the largest economic return. Social and commercial landlords in the Netherlands differ little from each other in that regard; the first mainly demolishes under its own management and the other sells before demolition occures. This explains why the demolition rates of social and rental property in Figure 1 are considerably higher than the owner-occupied counterpart (Thomsen 2005, 2023). And, like this, there are more questions to be answered.

The special issue 'Understanding Demolition' thus comes at just the right time.

The editorial (Huuhka 2023) states the special issue 'embarked to understand demolition as a phenomenon' and explore 'when, why and how demolition occurs with the aim to understand its environmental, socio-economic and cultural drivers, and consequences in policy and practice alike' and also the 'potential for avoiding building replacement (demolition and subsequent new build) and favouring retention'. The initiative for this special issue is to provide answers that are pressingly needed. It is an ambitious act whose importance can hardly be undervalued.

Demolition1 is principally a matter of behaviour and attitudes, but the role of the actors is often ignored. Huuhka's point is whether the role and business models of the construction sector needs to be reconfigured from the current emphasis on new construction to greater emphasis on stewardship (maintenance and renovation) of the existing building stock. This point is well-judged and to be welcomed. This point also makes policy measures - and thus knowledge-based insight - indispensable.

As stated above, demolition has mainly been studied from a rather one-sided technical or (property-based) economic perspective. Huuhka (2023) recalls that 'there has been fairly little problematisation in- or outside of academia whether and how demolition helps to build environmentally, economically and socially sustainable cities and when it is in fact helpful toward these goals'. Although large-scale demolition has always elicited criticism, e.g. Jacobs (1961), the explanation for this lies in the past.

Background

In recent years, awareness has grown that demolition imposes harmful effects on both people and the environment (Power 2010). More attention and research are being paid to it. And with good reason: construction and demolition waste is the largest waste stream in the European Union in terms of mass: 374 million tonnes annually with the largest part being demolition waste (EEA 2023).

A relatively new perspective is to regard the decay of buildings as time- and culture bound social behaviour i.e. a form of consumerism. This is when products (in this case, buildings) are discarded as better products become available (Anderson et al. 2018).

Even more harmful are the climate consequences, as our remaining emission budget is shrinking fast (IPPC 2023). Last but not least, the inhumane forced displacement of innocent residents is an unacceptable violation of their human rights (Rajagopal 2024). The harmfulness of unnecessary demolition can no longer be ignored. Anyone who still wants to demolish will have to demonstrate (according to proposed EU rules) that it is indispensable, that there is no alternative and that the rights of the residents are optimally respected.

At the end of the 19th century, large-scale slum clearance occurred for the creation of new urban areas, e.g. in Paris (1883) and Liverpool (1885). In many Western European countries, this coincided with the demolition of the fortress walls and ramparts of the medieval city and the transformation (including the devastation by two world wars) of the urban landscape. Demolition of large parts of city centres became the standard applied clearing tool especially for mass housing after WWII. Once the worst housing shortages were reduced, demolition continued in the same way with slum clearance.

It is thus not surprising that demolition has become an evident part of the mindset of builders. As a result, demolition has predominantly been studied from that mindset and technical viewpoint by technicians, planners, real estate managers and economists without much problematisation about necessity and consequences. Despite the availability of broader approaches (i.e. sociological case studies and interdisciplinary investigations), they were ignored as not relevant.

This brief timeline illustrates the impact of interests and behaviours of the actors involved, and why the mainstream of professional and academic attention has been quite single-sided.

Critique of the special issue

Huuhka (2023) uses the term 'phenomenon' as a characterisation of demolition. The term points at the holistic character of understanding. In scientific usage, a phenomenon means any event that is observable, both in terms of the physical appearance and properties, as well as the behaviour of the phenomenon and/or the actors involved (Sandywell 2011).

The approach as a phenomenon raises thus questions such as: What is demolition? What are the main features? When is it necessary and when not? What are the actors and what are their objectives and motives for demolition? What do we know about the decision making? At what levels of scale? What are the consequences and alternatives? And above all: What is needed for a better understanding?

The call for papers provided a more general description and dilemmas of the problem. Nevertheless, referring to the objective of this special issue and the main problems, a key question is: to what extent the contributions provide more insight in and understanding of 1) demolition as a phenomenon; 2) the role of behaviour, particularly in the role of interest driven conduct of the actors; 3) the consequences for climate, people and the environment; 4) to what extent the findings and outcomes are critically discussed and addressed, and 5) to what extent the outcomes are broadly applicable and generalisable. Also noteworthy is how, and using what type of research, the subject is approached.

Apart from the introductory paper by Huuhka, the special issue consists of 8 papers.2 My critique considers the extent they provide substance to the aforementioned questions.

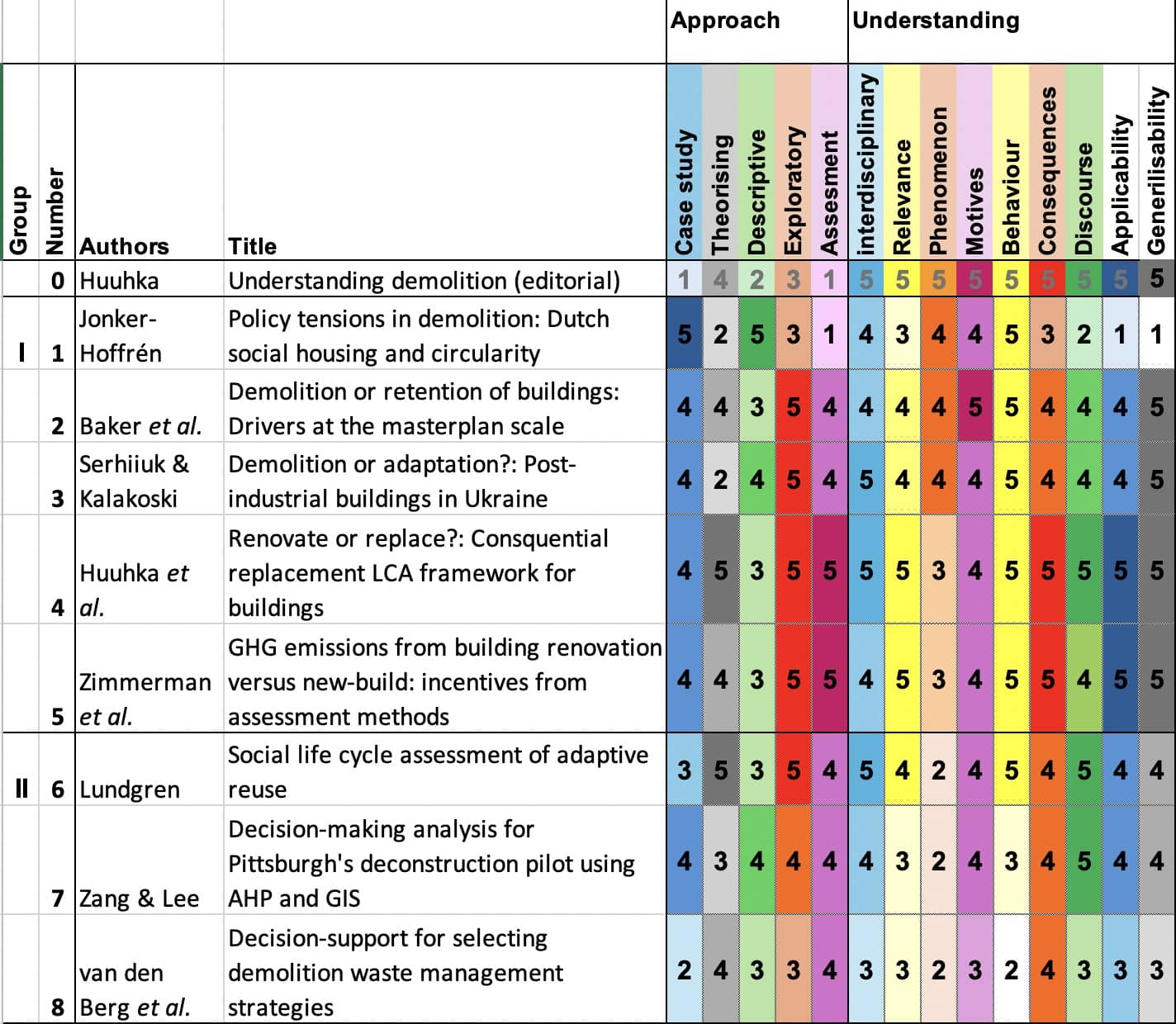

Key to right hand columns: 1=none, 2=little, 3=neutral, 4=well, 5=fully

This leads to the following remarks (Figure 2):

- Regarding the approach of demolition as a phenomenon, there are two different divisions: I) 5 papers that focus on the choice between demolition and preservation, and thus correspond most closely to that intention; II) 3 papers focus on the outcome of the decision as the field of study, adaptive reuse (1) or demolition (2).

- All 8 papers are to some extent based on case studies; in I) as a main part of the analysis, in II) also (1) and as a test of the result (2). Theory building is a strong component in 5 papers: I) 3, II) 2.

- Behaviour, and the underlying interests of the participants involved, plays a role in all 8 papers, ranging from I) a crucial part of the decision-making, to II) a more or less elaborated factor in the implementation of the decision.

- The relevance of most papers of I) is high; 2 papers stand out in terms of ground-breaking contributions to the actual urgent spearhead of GHG emissions (Huuhka et. al. and Zimmerman et. al.), and 2 on the comparison of demolition vs. retention / adaptation (Baker et al.), in particular in postwar areas (Serhiuk & Kalakoski). Also highly relevant is the contribution to the assessment of the-sometimes troublesome-social life of adaptive reuse (Lundgren).

The conclusion is that the overall contribution of the special issue begins to provide a valuable understanding of demolition, as a multiple-sided phenomenon with far-reaching consequences for people, nature and the climate, for now and the future. The special issue reflects the wider research landscape: demolition is under-researched and would benefit from targeted research funding. As building stocks age, the problems and issues raised in the special issue will increase in magnitude.

That begs for a follow-up. I would like to see more research and a further special issue on demolition. Buildings and Cities can play a prominent role in this sense, but it is vital that funding is provided for research, cooperation, exchange and theory development. Although several scientific organisations are active in this field, there is still no initiative to do so.

So, who will take the initiative?

Notes

1. Unless otherwise stated, the word 'demolition' in this paper refers to unnecessary demolition.

2. It is debatable whether Lundgren's paper belongs in the special issue. It actually is not about demolition apart from a few comments about the undesirability of the choice for and the applicability of the described assessment model to decision-making about demolition.

References

Anderson, S., Hamilton, K., & Tonner, A. (2018). "They were built to last": Anticonsumption and the materiality of waste in obsolete buildings. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 37(2), 195-212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743915618810438

Baker, H., Moncaster, A., Wilkinson, S.J. & Remøy, H. (2023). Demolition or retention of buildings: drivers at the masterplan scale. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), p.488-506. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.308

EC. (2019). The European Green Deal. (COM(2019) 640 final). Brussels: European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

EEA. (2019). Construction and demolition waste: challenges and opportunities in a circular economy. In: European Environmental Agency series Briefings. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/construction-and-demolition-waste-challenges. Full report: https://doi.org/10.2800/07321

Huuhka, S. (2023). Understanding demolition. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 927-937. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.398

Huuhka, S., Moisio, M., Salmio, E., Köliö, A. & Lahdensivu, J. (2023). Renovate or replace? Consequential replacement LCA framework for buildings. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 212-228. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.309

IPPC. (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. (H. Lee & J. Romero Eds. full edition ed.). Geneva: IPCC (UN).

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Jonker-Hoffrén, P. (2023). Policy tensions in demolition: Dutch social housing and circularity. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 405-421. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.305

Lundgren, R. (2023). Social life cycle assessment of adaptive reuse. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 334-351. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.314

Power, A. (2010). Housing and sustainability: demolition or refurbishment? Urban Design and Planning, 163(DP4), 12. https://doi.org/10.1680/udap.2010.163.4.205

Rajagopal, B. (2024). Resettlement after evictions and displacement: addressing a human rights crisis. (A/HRC/55/53). Retrieved from Geneva: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/sessions-regular/session55/advance-versions/A_HRC_55_53_AdvanceEditedVersion.docx

Serhiiuk, I. & Kalakoski, I. (2023). Demolition or adaptation?: post-industrial buildings in Ukraine. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 352-368. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.307

Syswov. (2023). Syswov; Statistische database bouwen en wonen. https://syswov.datawonen.nl/

Thomsen, A. (2005). Demolition of Social Dwellings in the Netherlands. derive, Zeitschrift für Stadtforschung, 2005 (Heft 19), 8-9.

Thomsen, A. (2023). Het slopen van sociale huurwoningen is niet duurzaam en niet sociaal. Paper presented at the Sturend aan de slag met volkhsuisvesting; Discussiedagen Sociale Huisvesting 2023, Soesterberg (NL). (English version in preparation)

Thomsen, A., Nieboer, N., & van der Flier, K. (2015). Analysing obsolescence, an elaborated model for residential buildings. Structural Survey, 33(3), 18. https://doi.org/10.1108/SS-12-2014-0040

van den Berg, M., Hulsbeek, L. & Voordijk, H. (2023). Decision-support for selecting demolition waste management strategies. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 883-901. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.318

Zhang, Z. & Lee, J.D. (2023). Decision-making analysis for Pittsburgh's deconstruction pilot using AHP and GIS. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 292-314. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.306

Zimmermann, R.K., Barjot, Z., Rasmussen, F.N., Malmqvist, T., Kuittinen, M. & Birgisdottir, H. (2023). GHG emissions from building renovation versus new-build: incentives from assessment methods. Buildings and Cities, 4(1), 274-291. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.325

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Reimagining circularity: actions for optimising the use of existing buildings

R Lundgren, R Kyrö, S Toivonen & L Tähtinen

Effective interdisciplinary stakeholder engagement in net zero building design

S Vakeva-Baird, F Tahmasebi, JJ Williams & D Mumovic

Metrics for building component disassembly potential: a practical framework

H Järvelä, A Lehto, T Pirilä & M Kuittinen

The unfitness of dwellings: why spatial and conceptual boundaries matter

E Nisonen, D Milián Bernal & S Pelsmakers

Environmental variables and air quality: implications for planning and public health

H Itzhak-Ben-Shalom, T Saroglou, V Multanen, A Vanunu, A Karnieli, D Katoshevski, N Davidovitch & I A Meir

Exploring diverse drivers behind hybrid heating solutions

S Kilpeläinen, S Pelsmakers, R Castaño-Rosa & M-S Miettinen

Urban rooms and the expanded ecology of urban living labs

E Akbil & C Butterworth

Living with extreme heat: perceptions and experiences

L King & C Demski

A systemic decision-making model for energy retrofits

C Schünemann, M Dshemuchadse & S Scherbaum

Modelling site-specific outdoor temperature for buildings in urban environments

K Cebrat, J Narożny, M Baborska-Narożny & M Smektała

Understanding shading through home-use experience, measurement and modelling

M Baborska-Narożny, K Bandurski, & M Grudzińska

Building performance simulation for sensemaking in architectural pedagogy

M Bohm

Beyond the building: governance challenges in social housing retrofit

H Charles

Heat stress in social housing districts: tree cover–built form interaction

C Lopez-Ordoñez, E Garcia-Nevado, H Coch & M Morganti

An observational analysis of shade-related pedestrian activity

M Levenson, D Pearlmutter & O Aleksandrowicz

Learning to sail a building: a people-first approach to retrofit

B Bordass, R Pender, K Steele & A Graham

Market transformations: gas conversion as a blueprint for net zero retrofit

A Gillich

Resistance against zero-emission neighbourhood infrastructuring: key lessons from Norway

T Berker & R Woods

Megatrends and weak signals shaping future real estate

S Toivonen

A strategic niche management framework to scale deep energy retrofits

T H King & M Jemtrud

Generative AI: reconfiguring supervision and doctoral research

P Boyd & D Harding

Exploring interactions between shading and view using visual difference prediction

S Wasilewski & M Andersen

How urban green infrastructure contributes to carbon neutrality [briefing note]

R Hautamäki, L Kulmala, M Ariluoma & L Järvi

Implementing and operating net zero buildings in South Africa

R Terblanche, C May & J Steward

Quantifying inter-dwelling air exchanges during fan pressurisation tests

D Glew, F Thomas, D Miles-Shenton & J Parker

Western Asian and Northern African residential building stocks: archetype analysis

S Akin, A Eghbali, C Nwagwu & E Hertwich

Latest Commentaries

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.

Lessons from Disaster Recovery: Build Better Before

Mary C. Comerio (University of California, Berkeley) explains why disaster recovery must begin well before a disaster occurs. The goal is to reduce the potential for damage beforehand by making housing delivery (e.g. capabilities and the physical, technical and institutional infrastructures) both more resilient and more capable of building back after disasters.