www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/retrofit-buildings-recovery.html

Retrofitting Buildings to Support the Recovery

Faye Wade (University of Edinburgh) highlights the importance of building retrofit for a

sustainable economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only does retrofitting

promise a major step toward a low carbon society, it also contributes to

increased GDP and jobs in the construction sector.

Action to manage the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic has resulted in loss of jobs and slowing of economic growth worldwide. A number of high profile organizations have now identified low carbon building retrofitting as a fundamental pillar for a green economic recovery (LGA, 2020; RICS, 2020; EC, 2020b; CCC, 2020; WWF, 2020). This article explains why buildings need to be retrofitted and the economic and employment potential of doing so, before exploring skills gaps and training prioritization.

The need to retrofit

The European Union's (EU) building stock is the largest single energy

consumer in Europe, contributing to 40% of energy consumption and 30% of greenhouse

gas (GHG) emissions (EC, 2020a). Reducing this is essential for meeting the

aims of the Paris Agreement and international climate targets. However, 80% of

today's buildings will still be in use in 2050 and 75% of this stock is energy

inefficient (EC, 2020a). Energy retrofitting, or the improvement of fabric,

controls, service and lighting as well as the provision of low carbon heat and

hot water, is essential for reducing energy demand and associated GHG

emissions. Rates of retrofitting are currently low, with the EU's 1% annual

rate of reduction of the (domestic and non-domestic) building stock's primary

energy consumption sitting way below what is needed (EC, 2019). In

the UK, the Government's Clean Growth

Strategy has set targets for as

many homes as possible to have an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) C rating

by 2035 (UK Government, 2017a). With 70% of the UK housing stock currently

falling below EPC C, this leaves 19 million homes to retrofit within 15 years

(Rosenow et al., 2018). Reducing energy demand and achieving targets will thus

require unprecedented speed and scale of efforts to retrofit the entire building

stock.

There are promising activities in some places. For example, the European Green Deal will support a 'Renovation Wave' of buildings, which aims to at least double the annual renovation rate of existing building stock (EC, 2020b). This initiative will seek to establish a Communication and Action Plan (EC, 2020a) that includes:

- regulatory instruments for stimulating volume retrofitting

- financial mechanisms to mobilise investment

- supporting skills and employment strategies

- leading by example

with retrofits of public sector buildings.

The Scottish Government's Energy Efficient Scotland programme takes a

similarly broad approach, incorporating a clear legislative framework alongside

the development of supply chains, consumer awareness and financing. The

programme, which aims for all homes to be at least EPC C by 2040 where

technically feasible and cost effective, has been piloted for the past 3 years

and is set to roll out across Scotland over the next 20 (Scottish Government,

2018).

Economic and employment benefits

The built environment and

residential properties in particular are the largest value infrastructure in

most countries; these buildings also usually have very high longevity. Economic

benefits of retrofitting could include the potential to extend the service life

of a building, and increase the real estate value. For example, retrofitting

Canadian office buildings can result in a decrease in operating costs, increase

in occupancy rates and an increase in rental revenue (Carlson & Pressnail,

2018). In addition, buildings that consume less energy could contribute to a

shifting and reduction of peak demand, alleviating pressures on the grid and

facilitating the use of renewable energy supply technologies.

Poor quality domestic buildings contribute to

higher-than-necessary energy demand and high levels of GHG emissions. In the

UK, there is a disproportionately large number of energy poor households in low

quality properties in EPC bands E, F and G (BEIS, 2018: 35), and those who are energy poor are

statistically more likely to report poor health and emotional well-being

(Thomson, Snell & Bouzarovski, 2017). If considering the indirect impacts

of ill-health - for example, absenteeism and reduced productivity - the

economic impacts of poor quality buildings are even higher. Indeed, energy efficient

office buildings have the potential to increase worker productivity by

approximately 12% (BPIE, 2020).

Improving

the building stock can reduce pressures on health services, increase well-being

and economic output, and lead to higher levels of disposable income and

associated spending. Thus, retrofitting programmes have the ability to boost

Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For example, modelling estimates suggest a

boost of £7.8 billion to the Scottish economy alone through the Energy

Efficient Scotland programme (Turner et al., 2018).

Further, construction and building retrofit is a labour-intensive activity. It has been estimated that for every €1 million invested in energy renovation of buildings, an average of 18 jobs are created in the EU (BPIE, 2020). This is roughly equivalent to the number of new jobs created per £1 million of UK Government grant funding invested in new innovation sectors such as biotechnology, medical equipment engineering, high-tech manufacturing. For example, £8 billion of UK Government investment in innovation research & development generated approximately 150,000 new jobs over 13 years (UK Government, 2017b).

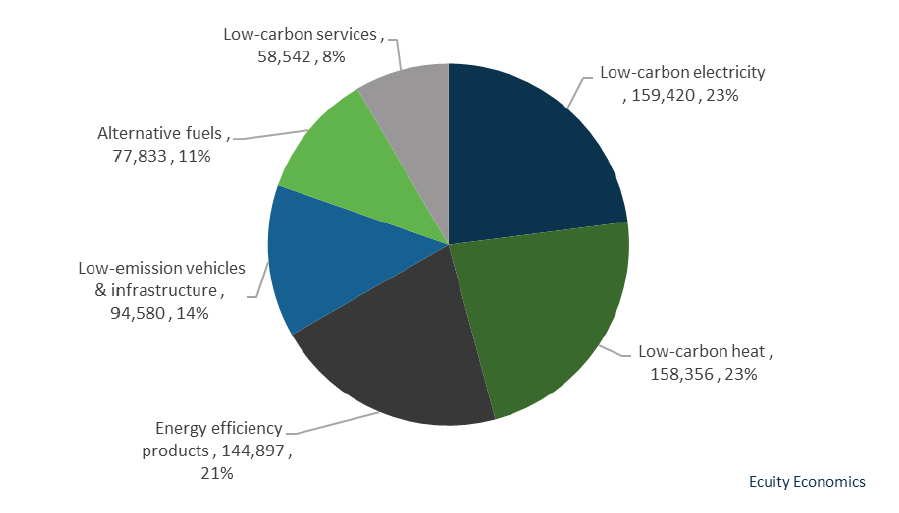

Meeting the EU's existing 2030 climate and energy targets can add 1% of GDP and create almost 1 million new green jobs (EC, 2020b). The significance of retrofitting is indicated by future low carbon jobs projections for England. Here, it is estimated that roughly 160,000 jobs will be in low carbon heat, whilst another 145,000 will be in energy efficiency products, including insulation, lighting and control systems (LGA, 2020).

Figure 1. Split of low carbon and renewable energy economy jobs in England by 2030 (Source: LGA, 2020: 7)

With these multiple benefits, scaling up rates of retrofitting will be crucial for achieving climate goals, and supporting the COVID-19 recovery effort.

Existing skills gaps and training prioritisation

The workforce needed for successful, wide-scale energy retrofitting is diverse. Work towards developing retrofitting standards across the UK includes Each Home Counts (Bonfield, 2016) and the associated PAS 2035 qualification, and the development of a Scottish Quality Mark (Cuthbert, 2019). The retrofitting process outlined in both cases includes assessment, installation, inspection and consumer protection. The variety of roles to be filled thus includes:

- Training and accreditation: the development of a network of courses and accreditation bodies to ensure that the workforce have opportunities to upskill and meet expected standards

- Advising: people who can offer advice to householders on retrofitting options and support them in accessing trusted tradespeople

- Assessment: building quality before and after retrofitting is assessed against EPC rating; this necessitates a workforce qualified to undertake SAP assessments

- Installing: a network of tradespeople and organisations qualified to fit insulation, glazing and low carbon heat.

- Coordination or design: a 'Designer' role has been identified in PAS 2035; this is an individual who will oversee whole house retrofitting, sequence works, and coordinate trades accordingly

- Inspection and enforcement: this is likely to require expansion of existing capacity within local authority Building Control

- Consumer protection: individuals who oversee consumer protection

standards and support consumer disputes (this is in line with the Consumer

Charter recommended in Each Home Counts).

New roles are emerging to deliver retrofit, and there is an additional

need to plug growing skills gaps in construction. In the UK, the number of

first year Further Education trainees fell from roughly 13,750 to 4,500 in the

wood trades, and 9,000 to 2,350 in bricklaying between 2007 and 2015

(ConstructionSkills, 2015). Additional regional skills gaps have been

identified. For example, shortages of bricklayers, joiners and painter &

decorators have been identified in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2019). A key

near-term (2020-2025) skills gap is in the design, specification and

installation of heat pumps (LGA, 2019). In addition, there are likely to be

local differences in need for and distribution of jobs. For example, regions

off the gas grid will need a workforce in the near-term qualified to fit

individual low carbon technologies such as heat pumps.

Filling these gaps, and delivering new skills for retrofitting will require a rapid shift in the UK's provision of existing vocational qualifications. The complex processes involved in energy retrofitting require 'energy literacy' across all construction roles (Clarke, Gleeson & Winch, 2017), and the related occupations listed above. In particular, design and construction teams need to be aware of the implications of their decisions on others' work (Owen, Janda & Simpson, 2019). Now is the time to develop new structures for the provision of training. This must include general knowledge of low energy construction and skills in understanding the 'whole house' needs, alongside tailoring to specific skills for the trade or role. In addition, COVID-19 has left many sectors (e.g. travel and hospitality) with increased levels of unemployment. It would be fruitful to explore how the transferable skills of these workers can be utilized in retrofitting. For example, experts in consumer protection from these sectors could potentially combine their existing knowledge with new training on buildings and energy to work within retrofitting.

Conclusions

With their benefits for the environment, economy, and employment, large

scale building retrofit programmes are exactly what is needed to recover from

the impacts of COVID-19 as well as transition the economy over the longer term.

A strategic approach to creating a qualified workforce for high quality

building retrofit would offer clear economic and environmental benefits in the

longer term. Such an approach is being pursued by the European Commission

through their Renovation Wave, and Scottish Government who are continuing

development of the Energy Efficient Scotland programme.

The benefits outlined here, coupled with vociferous campaigning for retrofit from numerous organisations, emphasize the need for multifaceted support for such schemes. Government roles include:

- providing incentives (through funding like the UK 'Green Homes Grant' scheme announced on the 8th July 2020 and the EU Renovation Wave scheme)

- capacity building through developing training programmes and supporting registration bodies, across all of the roles needed to deliver successful retrofit.

- creating strong support for homeowners (robust advice, supervision and validation; processes enabling occupant understanding and agency about operation and practices, post-occupancy evaluation, consumer protection)

- developing legislation and regulation to provide clear long-term energy performance targets

- enabling through providing oversight and supporting consumer protection.

The importance and delivery of such wide-scale energy retrofitting will be explored in a forthcoming special issue of Buildings & Cities: Retrofitting at Scale: Accelerating Capabilities for Domestic Building Stocks. The special issue will focus on the accelerated delivery of domestic energy retrofitting at different scales: national, municipal, neighbourhood and individual sites. It will draw out distinctions and complementarities for policies and delivery strategies for different scales, stakeholders, inhabitants and disciplines

References

BEIS (2018). Annual fuel poverty statistics report 2018 (2016 data).

England. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/annual-fuel-poverty-statistics-report-2018

Bonfield, P. (2016). Each Home Counts: an

independent review of consumer advice, protection, standards and enforcement

for energy efficiency and renewable energy. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/578749/Each_Home_Counts__December_2016_.pdf

BPIE (2020). Building Renovation: A kick-starter for the EU recovery.

Report prepared as part of the Renovate Europe Campaign. Available at: https://www.renovate-europe.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/BPIE-Research-Layout_FINALPDF_08.06.pdf

Carlson, K. & Pressnail, K. (2018).

Value impacts of energy efficiency retrofits on commercial office buildings in

Toronto, Canada. Energy and Buildings,

162: 154-162.

CCC (2020). Letter: Building a resilient

recovery from the COVID-19 crisis to Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Committee on

Climate Change. Available at: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/letter-building-a-resilient-recovery-from-the-covid-19-crisis-to-prime-minister-boris-johnson/

Clarke, L., Gleeson, C., & Winch, C. (2017). What kind of expertise

is needed for low energy construction? Construction Management and Economics,

35(3): 78-89.

ConstructionSkills (2015). Training and the

built environment 2014. Bircham Newton: CITB.

Cuthbert, I. (2019). Quality Assurance Short

Life Working Group Recommendations Report.

BEIS (2018). Annual fuel poverty statistics report 2018 (2016 data). England. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

EC. (2019). Comprehensive study of building energy renovation activities and the uptake of nearly zero-energy buildings in the EU. Prepared by Ipsos Belgium and Navigant for European Commission.

EC. (2020a). A Renovation Wave initiative

for public and private buildings. Roadmap. European Commission.

EC. (2020b). Europe's Moment: Repair and

Prepare for the Next Generation. Communication from the Commission to the

European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, The European Economic

and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0456&from=EN

LGA. (2020). Local green jobs -

accelerating a sustainable economic recovery. An Ecuity Consulting report for

the Local Government Association.

Owen, A., Janda, K. B., & Simpson, K. (2020). Who are the "middle actors"

in sustainable construction and what do they need to know? In Scott, L.,

Dastbaz, M. & Gorse, C. (eds) Sustainable Ecological Engineering Design [conference

proceedings], 191-204. Cham: Springer.

RICS. (2020). Retrofitting to decarbonise

UK existing housing stock: RICS net zero policy position paper. Royal Institute

of Chartered Surveyors. Available at: https://www.rics.org/globalassets/rics-website/media/news/news--opinion/retrofitting-to-decarbonise-the-uk-existing-housing-stock-v2.pdf

Rosenow, J., Guertler, P., Sorrell, S., & Eyre, N.C. (2018). The remaining potential for energy savings in UK households. Energy Policy, 121: 542-552.

Scottish Government (2018). Energy Efficient Scotland

Routemap. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/energy-efficient-scotland-route-map/

Scottish Government (2019). New housing and future

construction skills: adapting and modernizing for growth.

Thomson, H., Snell, C., & Bouzarovski, S. (2017). Health, well-being and energy poverty in Europe: A comparative study of 32 European countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(6): 584-20.

Turner K., Katris A., Figus

G., Low R. (2018). Potential wider economic impacts of the Energy Efficient

Scotland programme. Policy Brief. Centre for Energy Policy, University of

Strathclyde.

UK Government (2017a). Clean Growth Strategy. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clean-growth-strategy

UK Government (2017b) New jobs and billions to UK economy from innovation grants. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-jobs-and-billions-to-uk-economy-from-innovation-grant

UK Government (2020). 'Build, build, build': Prime Minister announces New Deal for Britain. Press Release. 30 June 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/build-build-build-prime-minister-announces-new-deal-for-britain

WWF (2020). A UK investment strategy: building back a resilient and sustainable economy. A Vivid Economics report for the WWF. Available at: https://www.vivideconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/4762-AUKInvestmentStrategy_Type_ONLINE.pdf

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.