www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/sustainability-single-households.html

The Sustainability Implications of Single Occupancy Households

Fresh thinking is needed on how we share spaces and services in dwellings and cities

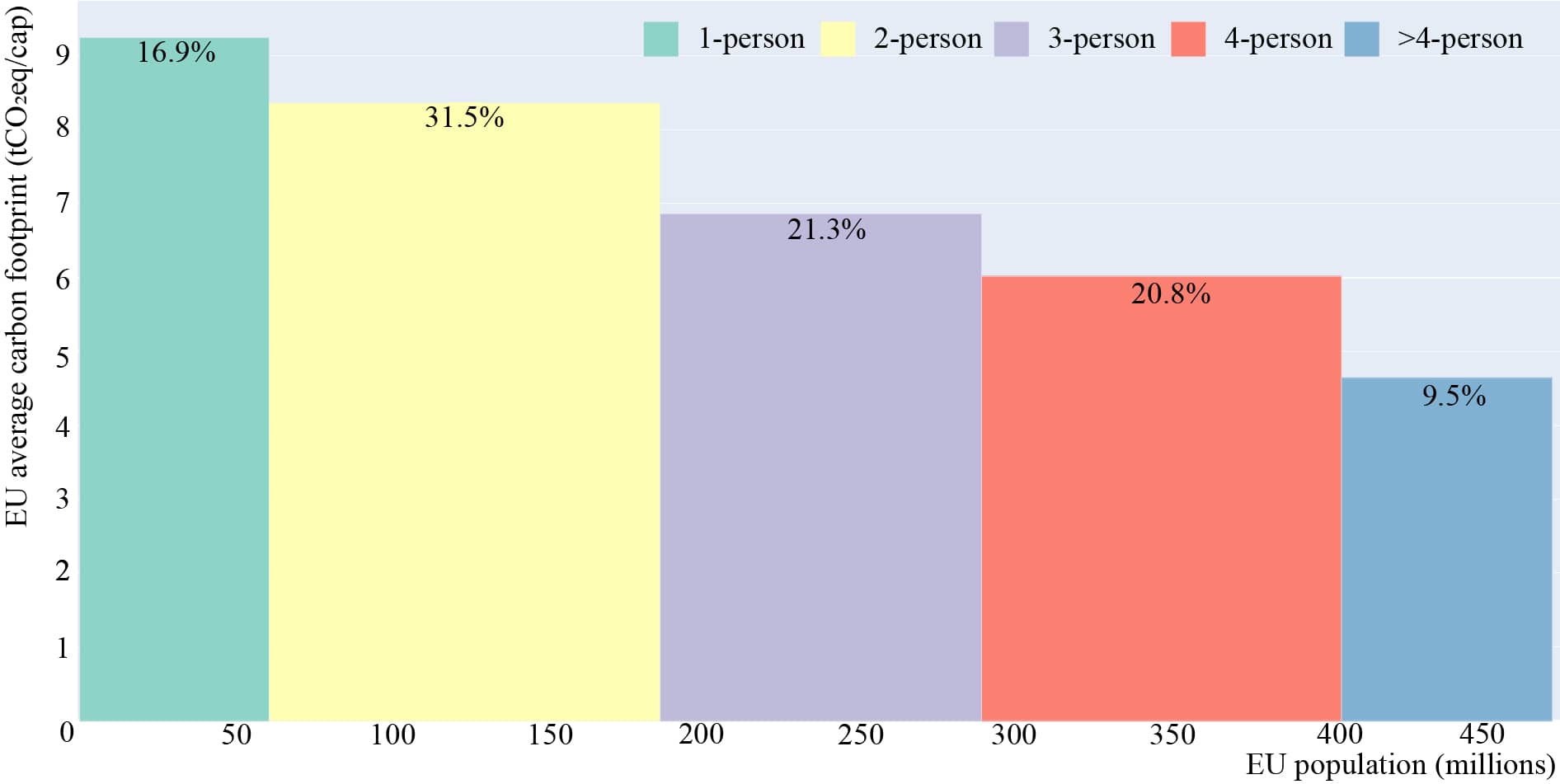

Single occupancy households consume more resources per capita, and demographics suggest single occupancy is now widespread in many countries. Environmental policies need to adjust to include per capita consumption to account for occupancy and efficient use of resources. Diana Ivanova, Tullia Jack, Milena Büchs and Kirsten Gram-Hanssen explain how the sharing of resources at domestic, neighbourhood and urban scales can have positive environmental and social impacts.

What do Oslo, Berlin and Paris have in common? 50% of households in these three European capital cities are occupied by single residents (Eurostat, 2018). Over the past 50 years, household size has been shrinking, not just in Europe but also in both developed and developing countries (Bradbury et al., 2014; Ortiz-Ospina, 2019). The actual number of single occupant households is predicted to rise substantially in the coming decades (Jennings et al., 2000). Affluence is crucial, with rising incomes in many countries likely to further encourage living alone (Ortiz-Ospina, 2019; Esteve et al., 2020).

There are also social costs associated with living alone. Some evidence suggests that single occupant households have the lowest life satisfaction among all household types (ONS, 2019; Gaymu et al., 2012). They are more likely to rent, have higher housing costs, less savings and thus decreased financial security (ONS, 2019). Not everyone who lives alone is lonely, but those that are may show more signs of anxiety and depression (ONS, 2020). There may also be increased health and death risks, particularly among elderly women (Harvard Health Publishing, 2012).

Living alone at various life stages

How do so many people end up home alone? Some common paths to living alone include young people leaving home to study or work, couples living apart for longer before moving in together (if at all), the dissolution of a relationship, or death of a partner.

Once a person lives alone, they are more likely to continue living alone (Chandler et al., 2004). This is especially the case for women (Liu et al., 2020). Studies show that women enjoy time alone more, have more satisfying friendships, and spend more time pursuing their interests than men do (DePaulo, 2019). Furthermore, once women get a taste for living alone, they are more concerned about doing more than their fair share of chores and caring for others.

The reasons why people live alone vary with life stage. There is a transitional phase early in life, in which forming a partnership or childbearing is delayed (Liu et al, 2020) in order to focus on education or start a career. In that period, it takes longer for men to move in with partners compared to women (Esteve et al., 2020). The gender trend reverses dramatically among the elderly, when the chances of women living alone are 2-4 times higher compared to those of men in Europe and North America (Esteve et al., 2020). At older ages, trends around the lengthened life expectancy and dissolution of partnerships tend to be the main drivers behind more elderly living alone.

A Canadian panel study examining the nature of living alone in a cohort aged 35-59 provides some important insights about increased solo living among middle-aged adults (Liu et al., 2020). Higher age, duration of living alone and not having a partner as well as living in an apartment increase the likelihood of keeping one's solo living status. The role of income may be contradictory as higher income increases the affordability of solo living, but it also increases one's attractiveness to potential partners. Other cultural and social factors may play a significant role, especially where living alone is voluntary and stable throughout the life course.

Policy implications

Despite evidence that living alone has significant sustainability implications, research and policy still emphasise smart technologies and buildings. To meet sustainability goals, GHG emissions accounting, assessment and management currently focus on design, construction and operation of building stocks (cf. Lützkendorf, 2020). This approach is insufficient to curb increasing household consumption (Gram-Hanssen et al., 2018).Building sustainability is important, but so is minimising resources required to provide services (e.g. heating, cooling, light, etc.) per person rather than per building. Policy needs to focus on how buildings are used, including how many people live in them. Key policy and research questions revolve around how other forms of living, (e.g. shared or co-housing, or tiny apartments) can be included in these metrics to reduce environmental impacts.

A policy focus on sharing can also extend to the cityscape, as services are often provided outside the home. Households may not need a car if public transport is available; public parks and greenspaces reduce the desire for private gardens; gyms, laundromats, restaurants and cafés, libraries and leisure facilities offer alternatives to in-home facilities; and co-working spaces to the home office. Sharing can be both simultaneous i.e. using the same spaces and resources at the same time, and sequential i.e. using spaces and resources at different times for maximum utility (Yates, 2018).

Sharing becomes increasingly viable as urban density increases. Sharing at the city level has exciting potential for reducing dependency on individualised resource ownership at the household level, and simultaneously reducing pressure on house size. Democratising ownership and governance of sharing practices are also key (Schor, 2016) in order to keep agency close to the end user and tailor more adequately to their needs.

Acknowledgements

Diana Ivanova and Tullia Jack are both funded by the EU's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Marie Sklodowska-Curie international fellowship, grant numbers 840454 and 891223. Milena Büchs receives funding from UK Research and Innovation, Centre for Research on Energy Demand Solutions, Grant number EP/R035288/1.

References

Bradbury, M., Peterson, M. N., & Liu, J. (2014). Long-term dynamics of household size and their environmental implications. Population and Environment, 36(1), 73-84. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-014-0203-6

Chandler, J., Williams, M., Maconachie, M., Collett, T., & Dodgeon, B. (2004). Living alone: its place in household formation and change. Sociological Research Online, 9(3), 42-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.971

DePaulo, B. (2019). 5 Reasons why so many women love living alone. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/living-single/201912/ 5-reasons-why-so-many-women-love-living-alone

Ellsworth-Krebs, K. (2020). Implications of declining household sizes and expectations of home comfort for domestic energy demand. Nature Energy, 5(1), 20-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0512-1

Esteve, A., Reher, D. S., Treviño, R., Zueras, P., & Turu, A. (2020). Living alone over the life course: cross‐national variations on an emerging issue. Population and Development Review, 46(1), 169-189. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12311

Eurostat, (2018) People in the EU - statistics on household and family structures. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=People_in_the_EU_-_statistics_on_household_and_family_structures&oldid=375234#Main_statistical_findings

Gaymu, J., Springer, S., Stringer, L. (2012). How does living alone or with a partner influence life satisfaction among older men and women in Europe? Population (English Ed.) 67(1), 43-69. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3917/pope.1201.0043

Gram-Hanssen, K., Georg, S., Christiansen, E., & Heiselberg, P. (2018). What next for energy-related building regulations?: the occupancy phase. Building Research & Information, 46(7), 790-803. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2018.1426810

Harvard Health Publishing. (2012). The challenges of living alone. Harvard Women's Health Watch. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/ the-challenges-of-living-alone

Ivanova, D., & Büchs, M. (2020). Household sharing for carbon and energy reductions: the case of EU countries. Energies, 13(8), 1909. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/en13081909

Jack, T. (2019). Nu vinner egennyttan över miljön: Kanske är det dags att tänka om. Behöver vi verkligen ha en tvättmaskin hemma? Sydsvenskan. https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2019-02-11/nu-vinner-egennyttan-over-miljon-kanske-ar-det-dags-att-tanka-om-behover-vi-verkligen-ha-en-tvattmaskin-hemma

Jennings, V., Lloyd-Smith, B., & Ironmonger, D. (2000). Global projections of household numbers and size distributions using age ratios and the Poisson distribution. 10th Biennial Conference of the Australian Population Association, Melbourne, Australia, (November), 30. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.572.2945&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Liu, J., Wang, J., Beaujot, R., Ravanera, Z. (2020). Determinants of adults' solo living in Canada: a longitudinal perspective. Journal of Population Research, 37, 53-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-019-09235-8

Liu, J., Daily, G. C., Ehrlich, P. R., & Luck, G. W. (2003). Effects of household dynamics on resource consumption and biodiversity. Nature, 421(6922), 530-533. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01359

Lützkendorf, T. (2020). The role of carbon metrics in supporting built-environment professionals. Buildings and Cities, 1(1), 676-686. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/bc.73

ONS - Office for National Statistics (2019). The cost of living alone, United Kingdom. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ families/articles/thecostoflivingalone/2019-04-04

ONS - Office for National Statistics. (2020). Coronavirus and loneliness, United Kingdom. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/datasets/coronavirusandloneliness

Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2019). The rise of living alone: How one-person households are becoming increasingly common around the world. Our world in data, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/living-alone

Schor, J. (2016). Debating the sharing economy. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 4 (3), 7-22.

Yates, L. (2018). Sharing, households and sustainable consumption. Journal of Consumer Culture, 18(3), 433-452. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540516668229

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.