www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/research-pathways/application-research.html

The Application of Research: Reconciling Simplicity and Rigour

RESEARCH LEGACY: personal reflections on a career in research

Edward Yan Yung Ng (Chinese University of Hong Kong) draws 5 conceptual and strategic lessons from his research career spanning building design, urban daylighting, urban ventilation and urban climate. Sound advice is offered to early career researchers. Amongst chief insights are the understanding of both theory and critical practice in order to frame a clear aspiration for research questions to pursue. Equally important is learning how to convey knowledge in language appropriate to end users (e.g. practitioners and policy makers).

Alfred N. Whitehead's "The Aims of Education" (Whitehead, 1967) profoundly influenced me at the start of my PhD at the University of Cambridge in 1987: one must have an aspiration about the aim of a certain subject matter, one must acquire a detailed knowledge of the subject matter, and one must find ways to utilize the knowledge for a useful purpose. Whitehead's ideas were echoed by the architect, educator and researcher Sir Leslie Martin when he talked about the education of an architect; paraphrased by Dean Hawkes: "Theory is the body of principles which explains and interrelates all the facts of a discipline. Critical practice it is the tool by which theory is advanced. Without theory and critical practice teaching can have no direction and thought no cutting edge." (Hawkes, 2001) These thoughts basically framed my scholarly journey in the past 35 years. Lesson 1: if you start your PhD with the wrong kind of thoughts, they are likely to stay with you forever.

As an early career researcher (1991- 98) I achieved very little. In hindsight, I was too obsessed with the detailed knowledge of the various subject matters themselves and had spent little effort on the aspiration of a study or its eventual usefulness. My focus was too much on the technicality of the subject matters and not enough on their meaning or application.

When I returned to Hong Kong in 1999, my research approach changed due to undertaking a project reviewing the existing building regulations on daylighting and ventilation of buildings. It provided a golden opportunity to examine theory and relate it to the design practices in the city. The existing building regulations were increasingly irrelevant as the city of Hong Kong densified with taller buildings closely packed together. In one meeting with regulators and architects, I argued that regulating daylight from the top of the building as opposed to controlling the building-height to street-width ratio has no scientific validity due to the law of tangents. Then I spent the next 2 hours lecturing them about sines, cosines and tangents! At the end of the meeting, I looked at their faces and I realized that most of them had no idea what I was talking about. Lesson 2: it is important for a building scientist to try to convey knowledge in language appropriate to end users (the practitioners).

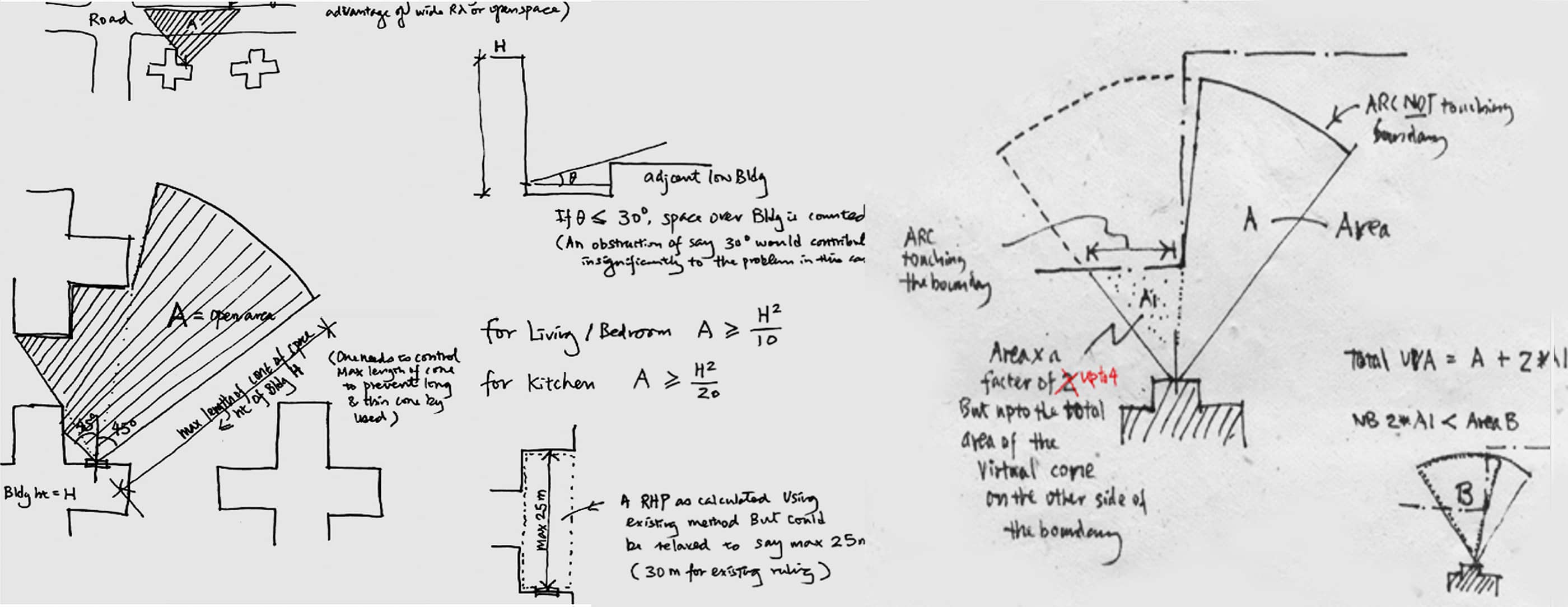

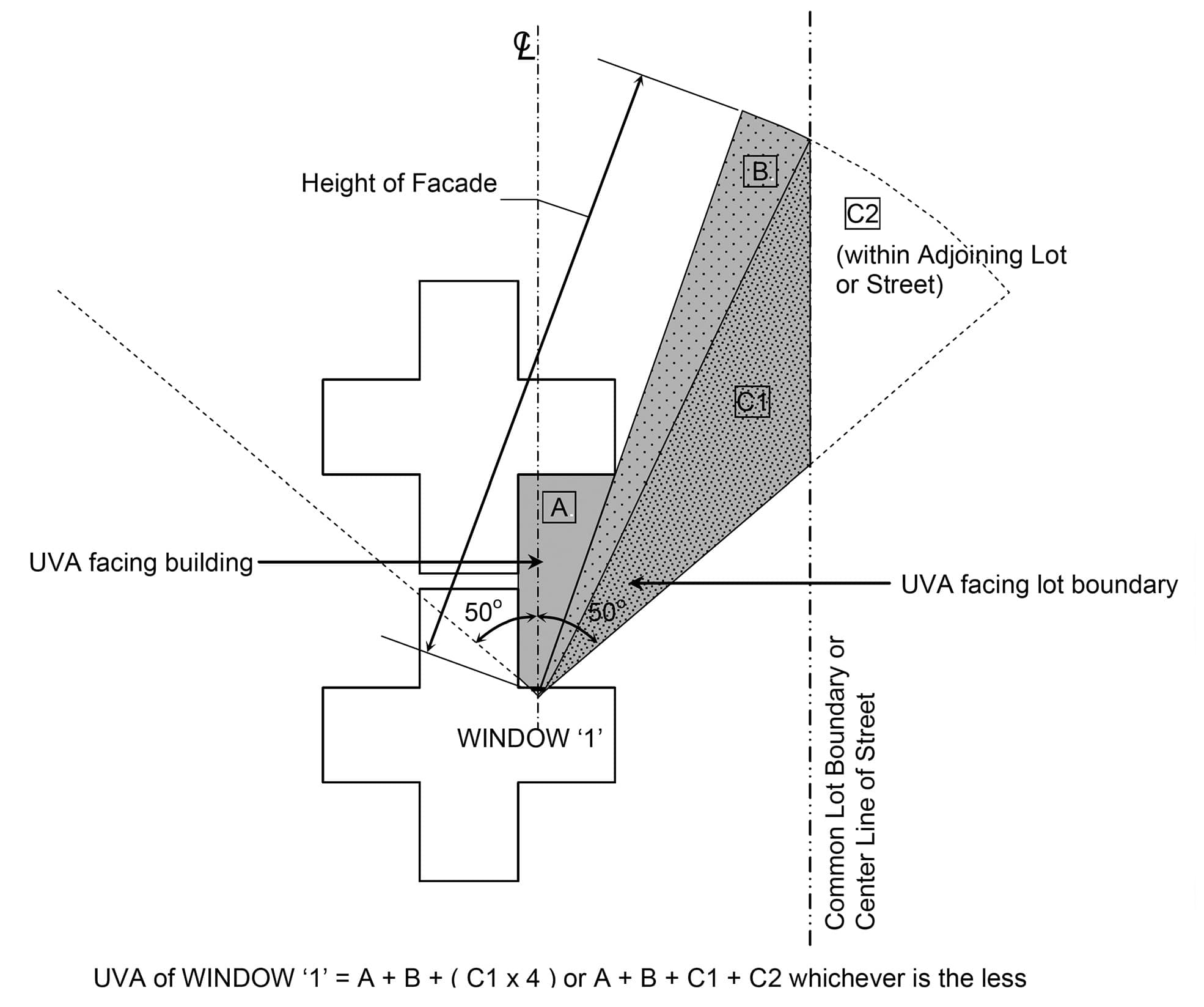

The theoretical idea behind the new regulations was "revolutionary". Before that, regulators around the world used the vertical angle of building height and street width to govern the availability of daylight to a window. This is a simple method if the ratio is in the order of 0.5 to 1. That is to say, if the street width is 20m, then the building opposite your window must not be taller than 20m. The sky above the roof of the building opposite you will give you the needed daylight. However, that rule breaks down when the ratio is 2 or more - as in Hong Kong. The solution is not to regulate the height of the buildings, but the gaps between buildings and the dimensions of the open space the window faces. The new building regulations use the idea of 'Unobstructed Vision Area.' (Building Department, 2003) This method can be graphically visualized by architects using their site plans. As such, they can find ways to design with it.

After the daylight study, in 2003 I was asked to conduct another study on urban ventilation for city planning by the government even though I knew almost nothing about urban ventilation at that time. Later, I discovered the reason I was invited was that I knew how to speak the language of practice. From my reading and background research, it became apparent there was no book or existing knowledge that could describe the urban wind environment in Hong Kong. The prevalent idea of the time was all about canyon flows. Most of the time it was about canyons of 1 to 1 ratio - situations one often found in European cities. Even when higher ratio wind studies were done, the conclusion had always been: don't do it! The existing literature never tried to deal with canyons of 3 to 1 or higher. I knew then that I needed to develop new knowledge. I hypothesized that controlling canyon ratios, i.e. building heights, would not be the answer. Instead, one might look at spaces-in-between and therefore develop the building-site coverage ratios as a more dynamic approach. This led to the development of the 'Air Ventilation Assessment (AVA) System' (Ng, 2006).

When developing the AVA System, I was mindful about how science should relate to practice, and discussed this with Shuzo Murakami of Tokyo University, an architect by training and an expert in building aerodynamics. His advice was stern - Lesson 4: whatever you develop, keep it simple. The art is to keep the simplicity but not lose the scientific rigour. While working on the AVA System, I teamed up with a few architectural practices to test its operation procedures - critical practice as Leslie Martin rightly put it. In December 2006, the government promulgated the AVA System (TC06-01, 2006). Since then, the AVA System has been in operation guiding the city's planning and property development, producing buildings with large holes in the middle (Figure 2).

Urban ventilation was not the only environmental answer to the dense living environment we have in Hong Kong. Mat Santamouris, Richard de Dear, Lutz Katzschner and others introduced me to several valuable ideas, including urban climatic mapping for planning. Immediately, I started to embark on my next adventure again in which I had no prior knowledge. I started to read books and papers on urban climate by Helmut Landsberg, Tim Oke, Baruch Givoni, and so on. For at least a year, I was again a humble student learning a new subject area. It was rejuvenating. Lesson 5: if you want to be a scholar, be humble, be curious and keep on learning all the time.

A further study on urban climate for planning enabled me to learn from and work with city planners who were the end users of this research. Eliasson (2000) enlightened me to systematically establish a working protocol to transfer scientific knowledge into practice. This led me to write on the need for the scientist to focus on communicating the concepts of "prevailing" and "criticality" (Ng, 2011). Basically, it was about how often an event happens and how serious the consequences of that event happening might be. I also argued that there was no need to fill practice with the most precise and accurate scientific information to make the right decision as, most of the time, this may confuse and make understanding difficult. Instead, one must communicate the information simply and sufficiently to preclude the wrong decision.

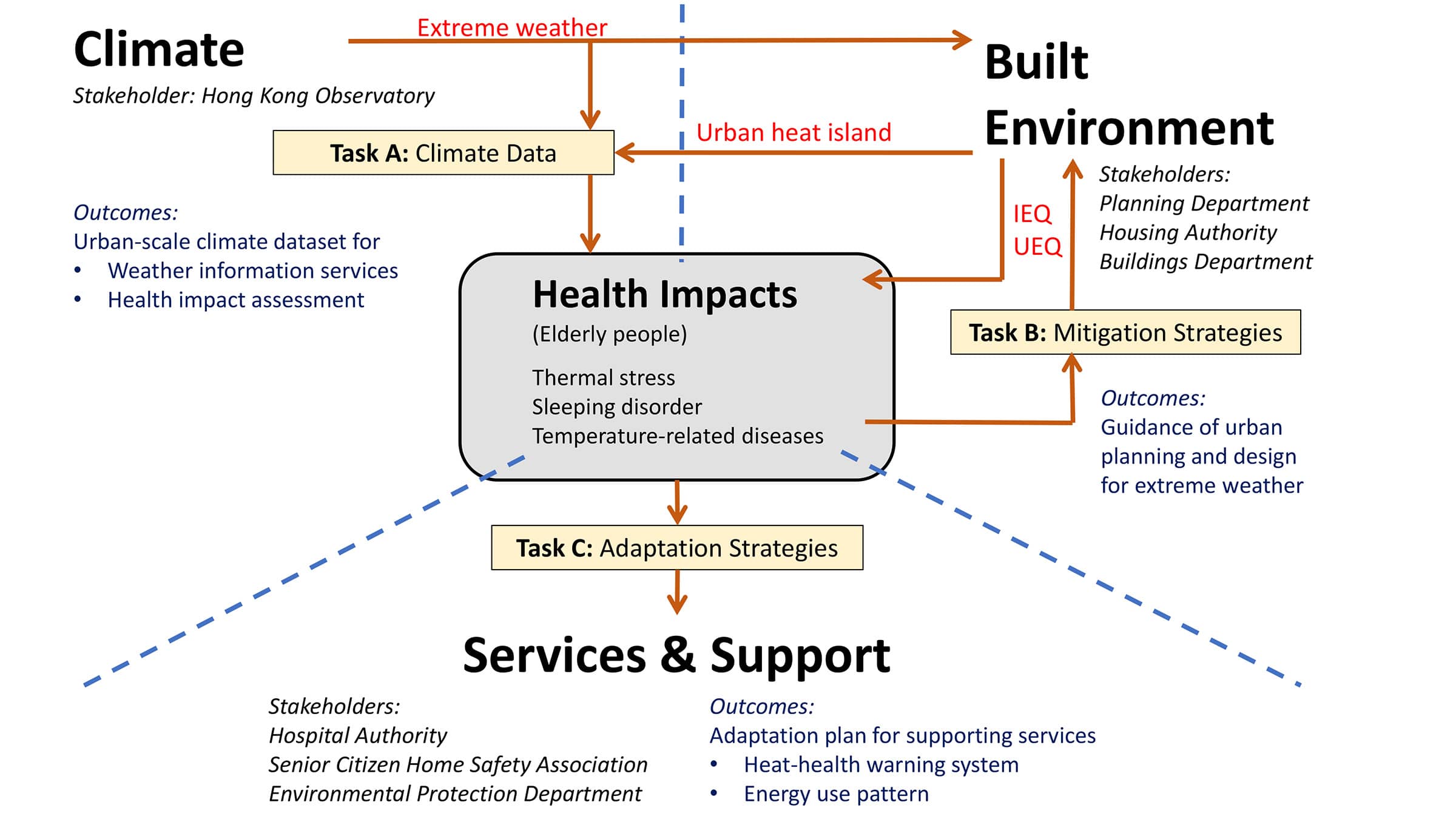

So far, my work has been to understand the

dense urban environment of Hong Kong as it is and how one could make it

better. A few years after the urban

climate map study, the government was interested in charting Hong Kong's urban

future- the 'initiative

Hong Kong 2030+.' (HKSARG, 2016) Again I had to start reading books about two

major changes that the government would need to address: climate change and demographic

changes. Hong Kong will face a more

challenging and unpredictable climate future with an ageing population and to

coordinate the study required developing a framework linking climate change,

the built environment and an ageing society (Figure 3).

Apart from the top-down scientific approach to understand the impacts of extreme weather on buildings and urban spaces, I started to work with our sociologist and public health colleagues to establish the needs of our older population. Field studies and surveys were conducted. Living habits, psychological and physiological responses were captured. The data would later be used to develop thresholds and adaptation measures. The work is still on-going and challenging since I have never worked with those beyond our built-environment discipline. Now I need to decipher what the social scientists, doctors, physicists, and elderly participants wish to tell me and find ways to put the often-conflicting pieces together.

Over the past 35 years I have pondered on the dialectics between theory and critical practice. I have moved from building design to urban design, and from a focus on the present to the future. Always bearing in mind Whitehead's three stage schema, I have come to believe that having an aspiration for a subject matter and finding a good way to utilize what one knows are the most difficult stages. The technical part in the middle is relatively easy. The aspiration part requires one to appreciate and be sensitive about the world, its people and the context. One needs a compassionate soul to seek out what needs to be done. I always tell my students: go out and see life first; then one knows what thesis one may need. Achieving a useful purpose requires one to be on the ground working with all the stakeholders. This is often the most difficult part for scholars who are more comfortable working in their silos, speaking only one kind of disciplinary language and following one methodological logic.

References

Buildings Department. (2003). APP130 Practice Note for Authorized Persons, Registered Structural Engineers and Registered Geotechnical Engineers. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government (HKSARG).

Eliasson, I. (2000). The use of climate knowledge in urban planning. Landscape and Urban Planning, 48, 31-44.

Hawkes, D. (2001). The Architect and the Academy linking practice and research. Architectural Research Quarterly, 4(1).

HKSARG (2016). Hong Kong 2030+. https://www.hk2030plus.hk/

Ng, E. (2006). Policies and technical guidelines for urban planning of high-density cities-air ventilation assessment (AVA) of Hong Kong. Building and Environment, 44-7, 1478-1488.

Ng, E. (2011). Towards planning and practice understanding of the need for meteorological and climatic information in the design of high density cities: a case study of Hong Kong. International Journal of Climatology, DOI:10.1002joc.2292.

TC06-01 (2006). Air Ventilation Assessments. HPLB and ETWB Technical Circular. HKSAR Government.

Whitehead, A. N. (1967). The Aims of Education and Other Essays. New York: The Free Press. (Reissue of the original 1929 edition)

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.