www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/research-pathways/household-energy-consumption.html

Making an Impact on Household Energy Consumption

RESEARCH PATHWAY: personal reflections on a career in research

Kirsten Gram-Hanssen (Aalborg University) reflects on the key drivers in her research career moving from engineering to work as a social scientist to understand inhabitants' energy consumption. Situated for many years within a governmental research institute dedicated to applied research, she highlights the challenges that researchers face for influencing public policy.

My interest in energy started in childhood during the energy crisis of the 1970s, and in high school I created a project on energy efficiency and prosumption in detached houses. This may give a false impression that my research career was very straightforward as my last 20 years of research has been on households' energy consumption. However, my career was not straightforward!

A detour

I went to a technical university in 1984, mainly because my feminist approach led me to study engineering just because this was a male dominated field. At that time, energy was not understood as being within a social context. This led me to question what technology is and how it relates to society, so I moved to the social science department at the technical university. Some questions of how technology and society shaped each other were answered here, but others were not. A practical question intrigued me: what is the best way to handle straw from farm fields (either making it into biogas or plough it back into the soil to improve fertility)? This started a long detour in my research career. In my master's degree, I worked on views of nature and ethics. In my PhD, I used this approach to compare different types of wastewater treatment. Situated at a social science department at a technical university, I did a PhD with a humanities approach, supervised by a young economist, Inge Røpke, and supported by a research environment of feminist thinkers. At that time, the technical university allowed students to pursue their own curriculum - something that is not possible today. I thought my PhD achieved some major insights, though soon I realized that doing a PhD does not change anything in the real world. Furthermore, I felt in a vacuum of not belonging to a discipline, not really being an engineer, a social scientist, a philosopher, or a feminist researcher.

A research career in understanding energy consumption

Pursuing a scientific career (then as well as now) implies short time employment. With two small children I was close to giving up, but luckily, I applied for a job as senior researcher at the Danish Building Research Institute (SBI). Only two years after my PhD I had a permanent position, perhaps more by luck and coincidence. Situated at a governmental research institute dedicated to applied research shaped my career, and energy consumption in the built environment was a path easier to fund compared to others. Although disappointed about my PhD never really doing anything (but what had I expected?), I started a career which happily aligned with my early interest in energy.

At SBI, I met Hal Wilhite who became a major inspiration with his unique approach combining social science research and energy policy. My aim was always to deliver results which could be useful in a policy context. So, did I succeed in that? To be honest, I do not think this was my greatest achievement. Raising funding and getting attention nationally was never the big issue. In some years I had several frontpage stories in national Danish newspapers and broadcasting. Stories about 'who consumes how much and for what purpose' were easy to sell to journalist. However, funding and publicity do not necessarily lead to changes in policy.

This can also be illustrated by the work on energy labels, energy retrofitting, rebound effect and changing norms of comfort. My research group collaborated with a broader international research community. To mention just a few, these include Majcen et al. (2013); Sunikka-Blank & Galvin (2012). Within this research context, from 2013 and onwards I led a major five-year research project, including researchers from social sciences, humanities and engineering called UserTEC.1 The project sought explanations and solutions to why the large technical potential for energy savings in the housing sector were not being realized. In terms of international collaboration and publications, the project was a success, specifically by relating technical and social understandings of how norms of comfort change together with the introduction of new technologies.2

In terms of impact on policy, the UserTEC project was less of a success. The results did not fit with the present policy context, even though the project team and advisory board did include both practitioners and policymakers. Energy and building authorities still wanted calculations on theoretical potentials of energy refurbishment despite the known shortcomings of such calculations. A key problem was the results could easily become subverted and used by those who are against a green transition, energy retrofitting and efficiency improvement. Another key problem is that changing a whole culture of professionals working in the administration takes time and are not achieved in one single project. Although efficiency is part of the solution, many other factors must be also included, notably, ways of reducing demand. Our research was better at pointing out the failure of existing policy, rather than suggesting new policies or actions. Furthermore, the appropriate actions were pertinent to other ministries and agencies rather than those dedicated to energy.

Understanding or saving the world?

Success in fundraising and publications means that our research group3 grew to 15 people. Funding is probably available for continued growth. A fundamental question that the research teams asks is: what is the right size and what should determine this? University leaders always want growth and the problems we address continue to be salient. However, I am losing faith that more of the same research is the answer. What type of research can deliver results to a policy framework that are not really open for fundamental changes?

While being frustrated about these questions, I realized that a major driver of my research is knowledge seeking. This allows me to grasp and combine things which I find are needed to understand the world.

Supported and encouraged by my university in 2017 I wrote a European Research Council (ERC) advanced grant application. In 2007 the Danish governmental research institute (SBI) became part of Aalborg University, and this made it easier for me to pursue more basic research compared to previously primarily doing applied research. Still, as an applied researcher with no well-defined discipline, my expectation for getting one of these prestigious basic research grants was not high, and my surprise and joy were great when it was awarded.4 For many years, my research has been inspired by theories of practice (Gram-Hanssen 2010) as developed by Schatzki (1996), Shove et al. (2012) and Warde (2005) amongst others. In my previous work I saw my role as translating theory into applied research within the built environment. Now, I created a new role to develop theories. While writing the application and actually doing the research, I realized that I have returned to some of my old questions from my PhD of understanding ethics, views of nature and technology (Gram-Hanssen 2019, 2021).

Some advice

My advice to others is to approach the act of writing a grant application as rewarding in itself. This can allow you to develop what you would like to work on, no matter if you get the grant or not. Writing an ERC application (or similar) can be seen as designing your future research career, allowing yourself time to develop ideas you really would like to work on. Should you not get the grant, you still have the ideas for other applications and future work.

My PhD was in-between several disciplines, not really linked to a research group or an international agenda. Reflecting on this, one of my conclusions is that breaking new ground as a PhD is too difficult. This is because one needs to link the research, situate it, and communicate it into a community who can discuss, criticize, and develop it. My PhD ended up on a shelf, whereas my later research has been cited, criticised and used.

My split background working as a sociologist, and partly educated as an engineer in the end turned out to be an advantage. Also, the fact that I had found some research environments to support my in-between discipline, specifically the European Sociological Association's (ESA) Network on Sociology of Consumption and the European Council of an Energy Efficient Economy (eceee) helped. Today many educational and research environments are transdisciplinary. Still, young researchers will find themselves at times on the edge of what the established researchers work on, as this is the nature of how research develops.

What advice would I give to these young researchers? I would like to say "follow what motivates you", pursue the questions which you think just must be answered. However, my own career also shows that being part of a community, learning and following common discussions are necessary. Following the money may be necessary too: it is possible to do this and be motivated by both problems and doubts.

Notes

1. For more information about UserTEC project, see https://www.usertec.aau.dk/

2. One of the publications was a special issue of Building Research and Information entitled "Energy performance gaps: promises, people, practices", which is illustrative of the work in UserTEC https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rbri20/46/1

3. Sustainable Cities and Everyday Practices at Aalborg University in Copenhagen, see www.en.build.aau.dk/research/town-housing-and-property/sustainable-cities-and-everyday-practice

4. For more information on my ERC advanced grant eCAPE see: www.ecape.aau.dk

References

Gram-Hanssen, K. (2010). Residential heat comfort practices: understanding users. Building Research & Information, 38(2), 175-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613210903541527

Gram-Hanssen, K. (2019). Automation, smart homes and symmetrical anthropology: non-humans as performers of practices? In C. Maller & Y. Strengers (Eds.), Social Practices and Dynamic Non-Humans: Nature, Materials and Technologies (235-253). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92189-1_12

Gram-Hanssen, K. (2021). Conceptualising ethical consumption within theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 21(3), 432-449. https://doi.org/10.1177/14695405211013956

Majcen, D., Itard, L. C. M., & Visscher, H. (2013). Theoretical vs. actual energy consumption of labelled dwellings in the Netherlands: Discrepancies and policy implications. Energy Policy, 54, 125-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.11.008

Schatzki, T. R. (1996). Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach

to Human Activity and the Social. Cambridge University Press.

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The Dynamics of Social Practice Everyday Life and How it Changes. SAGE.

Sunikka-Blank, M., & Galvin, R. (2012). Introducing the prebound effect: The gap between performance and actual energy consumption. Building Research & Information, 40(3), 260-273. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2012.690952

Warde, A. (2005). Consumption and theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 5(2), 131-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540505053090

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Learning to sail a building: a people-first approach to retrofit

B Bordass, R Pender, K Steele & A Graham

Market transformations: gas conversion as a blueprint for net zero retrofit

A Gillich

Resistance against zero-emission neighbourhood infrastructuring: key lessons from Norway

T Berker & R Woods

Megatrends and weak signals shaping future real estate

S Toivonen

A strategic niche management framework to scale deep energy retrofits

T H King & M Jemtrud

Generative AI: reconfiguring supervision and doctoral research

P Boyd & D Harding

Exploring interactions between shading and view using visual difference prediction

S Wasilewski & M Andersen

How urban green infrastructure contributes to carbon neutrality [briefing note]

R Hautamäki, L Kulmala, M Ariluoma & L Järvi

Implementing and operating net zero buildings in South Africa

R Terblanche, C May & J Steward

Quantifying inter-dwelling air exchanges during fan pressurisation tests

D Glew, F Thomas, D Miles-Shenton & J Parker

Western Asian and Northern African residential building stocks: archetype analysis

S Akin, A Eghbali, C Nwagwu & E Hertwich

Lanes, clusters, sightlines: modelling patient flow in medical clinics

K Sailer, M Utley, R Pachilova, A T Z Fouad, X Li, H Jayaram & P J Foster

Analysing cold-climate urban heat islands using personal weather station data

J Taylor, C H Simpson, J Vanhatalo, H Sohail, O Brousse, & C Heaviside

Are simple models for natural ventilation suitable for shelter design?

A Conzatti, D Fosas de Pando, B Chater & D Coley

Impact of roofing materials on school temperatures in tropical Africa

E F Amankwaa, B M Roberts, P Mensah & K V Gough

Acceptability of sufficiency consumption policies by Finnish households

E Nuorivaara & S Ahvenharju

Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse

É Savoie, J P Sapinski & A-M Laroche

Cooler streets for a cycleable city: assessing policy alignment

C Tang & J Bush

Understanding the embodied carbon credentials of modern methods of construction

R O'Hegarty, A McCarthy, J O'Hagan, T Thanapornpakornsin, S Raffoul & O Kinnane

The changing typology of urban apartment buildings in Aurinkolahti

S Meriläinen & A Tervo

Embodied climate impacts in urban development: a neighbourhood case study

S Sjökvist, N Francart, M Balouktsi & H Birgisdottir

Environmental effects of urban wind energy harvesting: a review

I Tsionas, M laguno-Munitxa & A Stephan

Office environment and employee differences by company health management certification

S Arata, M Sugiuchi, T Ikaga, Y Shiraishi, T Hayashi, S Ando & S Kawakubo

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Will NDC 3.0 Drive a Buildings Breakthrough?

To achieve net zero GHG emissions by mid-century (the Breakthrough Agenda) it is vital to establish explicit sector-specific roadmaps and targets. With an eye to the forthcoming COP30 in Brazil and based on work in the IEA EBC Annex 89, Thomas Lützkendorf, Greg Foliente and Alexander Passer argue why specific goals and measures for building, construction and real estate are needed in the forthcoming round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC 3.0).

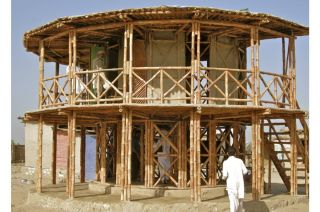

Self-Organised Knowledge Space as a Living Lab

While Living Labs are often framed as structured, institutionalised spaces for innovation, Sadia Sharmin (Habitat Forum Berlin) reinterprets the concept through the lens of grassroots urban practices. She argues that self-organised knowledge spaces can function as Living Labs by fostering situated learning, collective agency, and community resilience. The example of a Living Lab in Bangladesh provides a model pathway to civic participation and spatial justice.