www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/research-pathways/insights-socio-ecological.html

Journey to a Socio-ecological Agenda

RESEARCH LEGACY: personal reflections on a career in research

Marina Fischer-Kowalski considers the key drivers in her interdisciplinary career linking social metabolism and material flow accounting that led to the creation of economy-wide energy and material flow analysis (MEFA). Research into broad, complex issues cannot be done alone. Insights and advice are offered on intensive multidisciplinary collaboration.

My beginnings

After a PhD in Sociology in 1971, I spent the following ten years of research across the social sciences at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Vienna (Institut für Höhere Studien, Wien - IHS). One key collaborative research product was a report (and then a book), based upon public statistics and other sources, on the evolution of social inequality in Austria during the previous decades. We showed that all groups became better off, but continuing robust differences remained between (small) farmers and blue collar workers on the one side, white collar workers and small business on the other. These differences involved a range of inter-related issues: economics, education, cultural representation in the media, housing conditions, and in the life chances for their children. We showed that for those in the top income segment, there existed hardly any statistical information (of the kind Thomas Piketty now collects globally). Gender differences, during that period, though, had ameliorated.

The topic was viewed as highly political. It took six years, seven prominent international reviews (e.g. from J. Habermas, J. Galtung, and A. Giddens) and a legal complaint to the science minister to have my work accepted as a 'habilitation', the traditional requirement for the right to teach at universities. University professors saw me as a 1968 student radical: too critical of mainstream positions and lacking respect for authorities. While waiting for a decision, I followed this agenda on the international level, preparing reports on differential quality of life for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris.1 Back in Vienna, and with two small children, I received a job offer from an unconventional, interdisciplinary institution that was jointly run by 8 universities.2 My role was to develop a research group on 'environment and society'. They rented two rooms for me from a vibrant civil society organisation which was gaining its profile by supplying the public with the analysis of - post Chernobyl - radioactivity in food items.3 Thus I found myself surrounded by passionate young people from various science backgrounds on whom I could draw as teachers for me, and as experts. Publishers financed a first book that compared the state of the environment, policies and administrative action across the 9 Austrian states - a delicate issue as one state then threatened to sue us for harming its tourism interests. But everything went well and the book became a success.

This work and context allowed me to transition from the social sciences (that typically don't care about nature at all) towards an interdisciplinary agenda that fascinated me both intellectually and politically. My lesson learnt during this research was that it does not help to document the damages done to the environment. Instead, the focus must consider the processes, interests and constraints that trigger them. This requires a framework of theoretical concepts and methods equally legitimate for scientific and policy reference systems. Without such an approach, it does not make sense to struggle with hundreds, if not thousands of different wastes and pollutants, as was the current issue of that time.

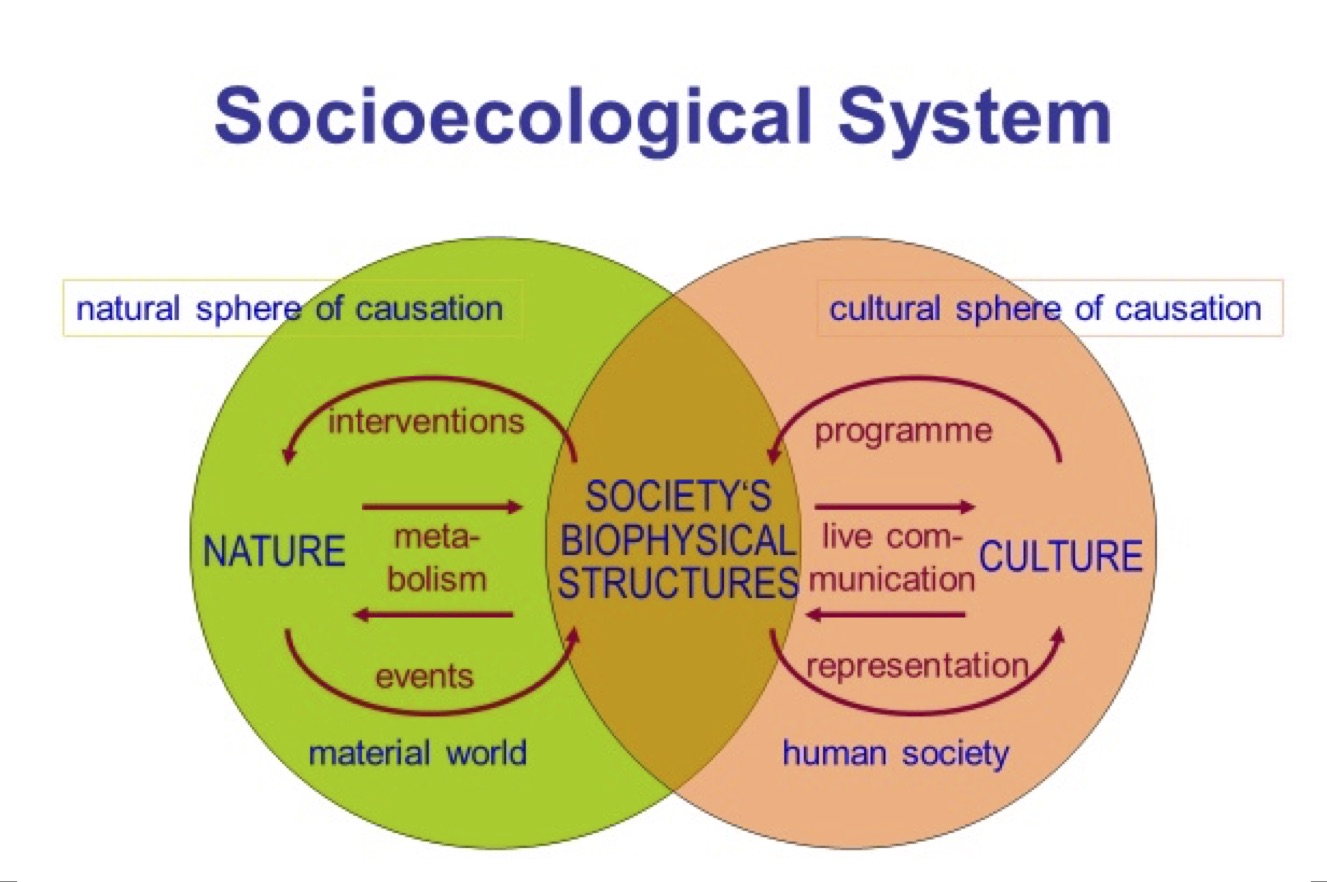

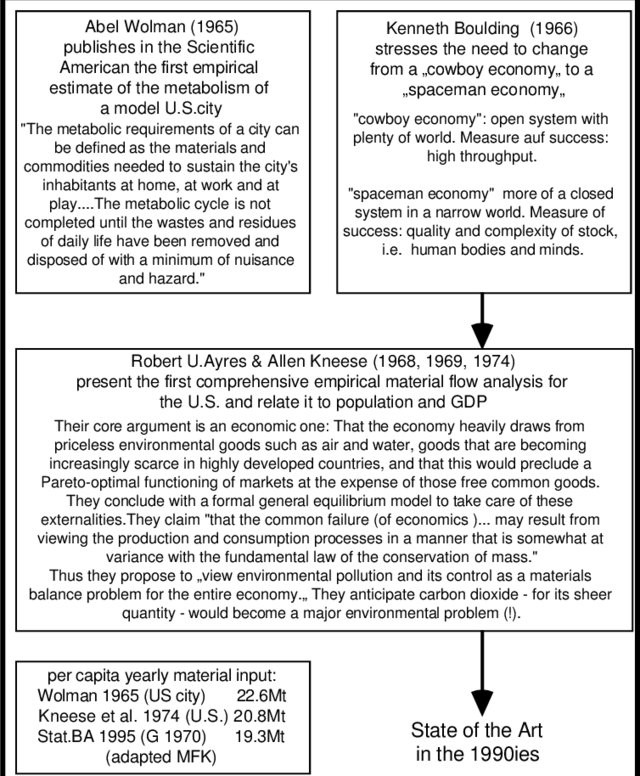

The Austrian public administration, fortunately, was willing to fund research that would help to sort out and bring structure to the messy situation across environmental issues. In a very young team recruited from the politically engaged students and graduates around me, we developed the two concepts that would guide future work: 'metabolism' and 'colonization'.4 Metabolism as a term derived from Marx's reasoning about society's material base: it describes the input of natural resources to produce and maintain society's biophysical structures, namely its human and animal population, and its man-made infrastructures. From this material input, there derive the commodities on the market, and the outputs of wastes and emissions. Austria became the first country in the world which published a comprehensive quantitative overview of its metabolism, the material base of its economy.

'Colonization', the second key term, referred to the societal use of knowledge, skills and resources to intervene into subsystems of the environment and modify them according to its interests and needs, such as by agriculture, breeding or medical immunisation, but also by trivial macro-interventions such as damming rivers and paving roads. With this conceptual outfit, society as a cultural and historical entity was brought into the picture of environmental concerns.

Steps towards international institutionalisation of the metabolism metric

A final step towards international acceptance of the metabolism metric from my part happened through membership in UNEP's International Resource Panel,7 first under the leadership of Ernst von Weizsaecker, and then Janez Potocnik, the former European Commissioner for the Environment. Over a decade, the panel met twice a year for several days in various places around the world, designing reports and discussing their outcome. In 2019, for example, it published a 'Global Resources Outlook', displaying time series indicators on the metabolism of 200 countries since 1970, following the methodology we had developed, plus the environmental and health impacts of this resource use. Once again it was demonstrated that 'decoupling' resource use from economic growth was largely illusionary. Although some rich countries could stabilize their resource consumption despite economic growth, this led to a rise in other (often less developed) countries who delivered the resources and consumer goods.8 Altogether, human material resource and energy use keeps exploding - maintaining direction towards environmental collapse and resource depletion in a finite world.

The key for success: long-term egalitarian multidisciplinary collaboration

My empirical research, the struggle for adequate notions and theories, and the applications in political and administrative processes, throughout the last 30 years have been a product of very intensive multidisciplinary collaboration. The original team, emerging in the late 1980s, consisted of a biologist, a chemist, a physicist, a technical engineer, a historian, an economist, a philosopher, and a sociologist (me). Later there came botanists, architects, landscape planners, political scientists. I was the oldest, and had most experience in fundraising. The academic institution provided limited financial support. Only my and the secretary's salary, plus the workspace rent were provided. With my background in inter-institutional and international collaboration, I acted as the team leader and remained in that role for 30 years - across collective institutional shifts (our institute was later incorporated into one university, and established a regular masters program in human and social ecology, and then into another),9 and a long phase of growth and increasing international academic standing.

Very early on, we practiced elaborate organisational development: weekly meetings for joint decision-making, periodic team seminars exposing ourselves to new approaches, using not only intellectual, but also creative and playful tools, and annual retreats to reflect our scientific, economic and organisational development, with the help of professional advisors. We fought our conflicts and crises - but we were able to keep the core team together across all those years. If some of them accepted assignments elsewhere, then collaboration continued. Newly recruited members to the team willingly adjusted to the established organisational customs, and these customs survived the two major institutional shifts.

In hindsight, I still find this astonishing. I tend to interpret it as an outcome of a) our diversity, b) our non-hierarchical but well-structured organisation, and c) our interactivity. The diversity greatly helped: everybody possessed knowledge that the others lacked and that was required for the overall insight - thus fostering collaboration instead of competition. The egalitarian spirit allowed everyone to contribute, but no one to impose opinions or insights on others. The high interactivity allowed for intellectual struggles to actually lead to shared insights and joint concepts.

Today, this is more difficult. The Institute for Social Ecology now encompasses more than 30 people; the lead scientists (now in the position of professors) are more distinct from the others than before, and they are terribly busy. The current overall university organisation is more bureaucratic, costs us more time, and we need to keep fighting for our rights to a degree of self-determination. Our academic reputation has earned us some licence. However, one example of the top-down burden is the practices to educate our master students jointly in a special program in team teaching are being challenged. At the same time, the international structure of how science is organised, has changed: both the grant system and the publication system. Most research now depends on being able to organise grants. Previously, we were among the fortunate minority who could successfully secure funding. Now the process is more difficult and less forseeable with many more researchers competing for limited funds. The publication business is getting ever more quantity-oriented: prestigious accounting systems compete for attention and services. The internal and external pressures to publish make it difficult to spend sufficient time and thought. It's no longer viable to take, say, a year as a team to thoroughly think and discuss some important modification of your approach and then come up with a key publication.

Motivation: curiosity driven and policy responsibility driven

What drives me? What makes me keep going for funding, agree to reviewing other people's work, accepting masters and dissertation outlines, organising conferences, giving presentations, writing articles and books? Why was I willing to and successful in running for the presidency of scientific societies, such as the Society of Industrial Ecology ISIE (2007-09) and the International Society for Ecological Economics ISEE (2013-2018)? Why was I willing to preside the Scientific Advisory Board of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research PIK (2002-2010) in a difficult transitional phase? Was it for a personal reputation? I obviously like if people know me and refer to my work, and if I am able to inspire students, colleagues and public audiences to accept certain questions and answers as relevant. But I don't spend time on following my reads and citations, and I do not invest into keeping my records properly updated. It definitely was not for money - most of these tasks rather cost than earn you money. I think it was a feeling of responsibility for concerns I found relevant and identified with - and often for people I liked and respected.

Also curiosity has always been a strong motivation. I can spend nights with historical databases for England to check when the first coal mines were inherited by someone, as a clue for dating the beginning of coal mining in that country, as part of a quest to see whether the Cromwell era had already been marked by the growth in employed labor enabled by the availability of coal for heating and cooking in cities. This developed into a research agenda that inspired me intellectually (apart from other funded research) for several years and resulted in an article on the close link between the transition to fossil fuel use and the occurrence of social revolutions, documented by sophisticated statistics for 70 countries across the past few hundred years up to the present.10

The desire to influence public policy is also a key motivation. My comparative work on countries' social metabolism, documenting the huge international inequality in the control over natural resources, makes me feel responsible as being among the beneficiaries. Energy is the variable most closely associated to GDP; major social and economic wealth was brought about in (my) half of the world through the energy-richness facilitated by cheap fossil fuels. The other half of the world is trying to catch up, while the rich industrial countries worry about maintaining their growth of GDP. How can we manage the major change that will be required to get off this track - or else head for a climate catastrophe?

In the face of such grand challenges that I

can't really resolve, it is heart warming to also work at a smaller scale: the

sustainability transition of a Greek island.11 This involves a range of research issues and collaborations with Greek

scientists and in particular also with locals, partly as so-called "citizen

scientists": how to achieve a drastic reduction of the number of free roaming

goats that destroy the mountain forest and vegetation cover, leading to

catastrophic impacts of heavier weather events; how to overcome obstacles to a proper

legalisation and establishing a management for the envisioned large

conservation areas on land and sea, support the municipality in warding off

plans to establish huge windfarms across the (protected) mountain range for the

export of electricity, and instead finding smart ways for a local transition to

renewable energy feeding sustainable forms of tourism.

Notes

1. This program, supported by a large number of countries worldwide, was finally stalled by an intervention from the US who claimed that income levels were sufficient information on quality of life, the rest were dispensable.

2. The 'Interuniversity Institute for Interdisciplinary Research and Teaching' (IFF: Interuniversitäres Institut für Forschung und Fortbildung)

3. The rainfall containing radioactive particles from the nuclear accident in Chernobyl, Ukraine, had quite an impact on Austrian territory.

4. Members of this original team are still pillars of our later Institute of Social Ecology, now part of the University of Life Sciences and Natural Resources, Vienna, and co-editors of our joint book, in which these core concepts still figure prominently. See Haberl, H, M.Fischer-Kowalski, F.Krausmann and V.Winiwarter (eds). (2016). Social Ecology. Society-Nature Relations across Time and Space. Springer.

5. Funding for the workshops came from European Commissions Directorate General on the Environment. The workshops were a collaboration between the Wuppertal Institute (Stefan Bringezu), Leiden University (René Kleijn), Statistics Sweden (Viveka Palm) and Vienna Social Ecology (Marina Fischer-Kowalski).

8. Fischer-Kowalski, M., M. Swilling, E.U. von Weizsäcker, Y. Ren, Y. Moriguchi, W. Crane, F. Krausmann, et al. (2011). Decoupling Natural Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth. Technical Report. Nairobi: United Nations Environmment Programme.

9. The whole IFF, including our institute, became a faculty at the Alpen Adria University, Klagenfurt, in 2003. Later, in 2018, Klagenfurt University decided to dissolve its Vienna site, and the Institute for Social Ecology with all personnel and equipment became part of the Department for Economic and Social Sciences at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna.

10. Fischer-Kowalski, M., E. Rovenskaya, F. Krausmann, I. Pallua and J. R. Mc Neill. (2019, January). Energy Transitions and Social Revolutions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 138, 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.08.010.

11. Fischer-Kowalski, M., M. Löw, D. Noll, P. Petridis and N. Skoulikidis. (2020). Samothraki in Transition: A Report on a Real-World Lab to Promote the Sustainability of a Greek Island. Sustainability, 12(5),1932. .

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.