www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/constructing-consumer-focused-industry.html

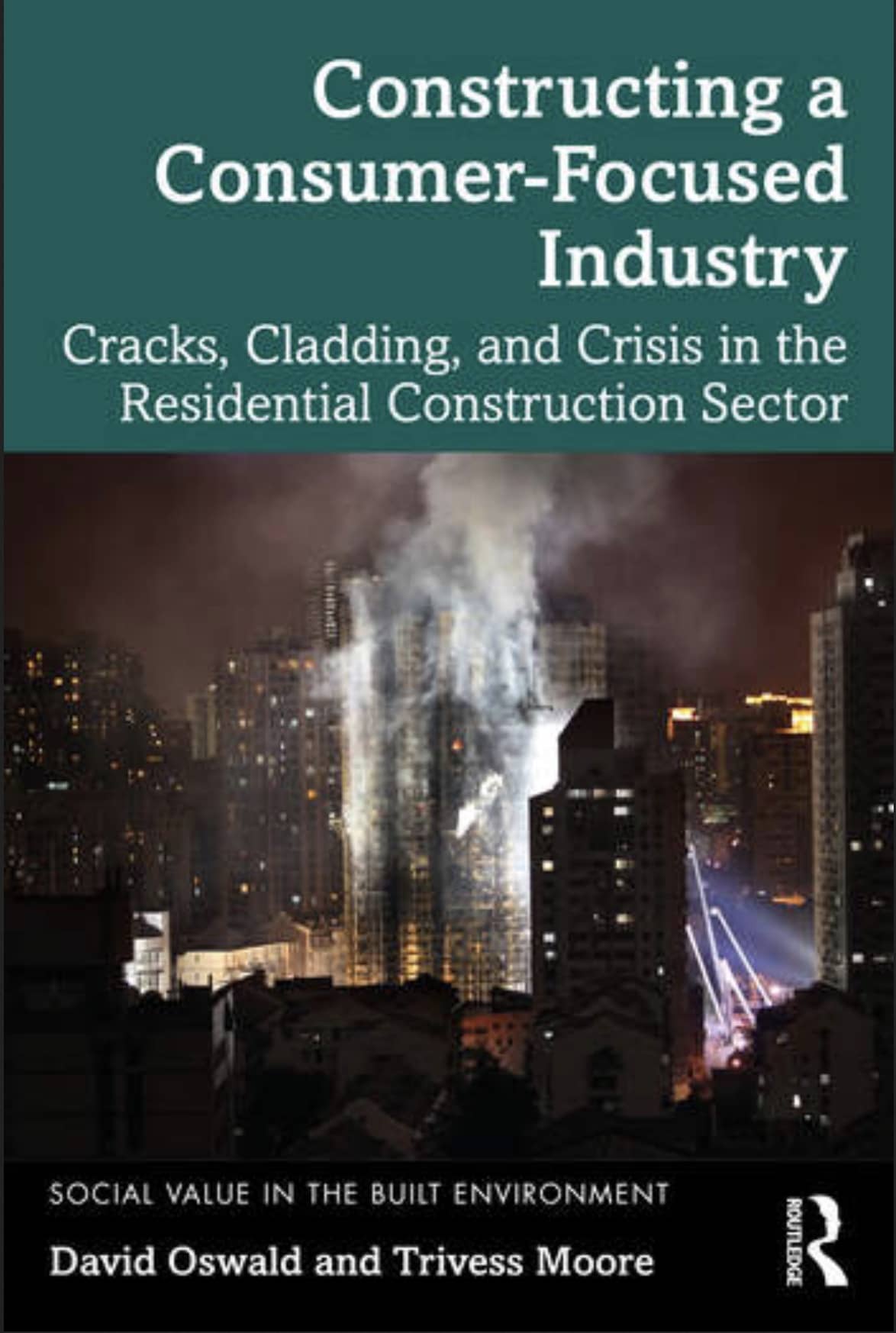

Constructing a Consumer-Focused Industry: Cracks, Cladding and Crisis in the Residential Construction Sector

By D. Oswald and T. Moore. Routledge, 2022, ISBN 9781032007311

Kay Saville-Smith (CRESA, Aotearoa NZ) reviews this book which chronicles deep, disturbing problems in the creation of dwellings. Dangerous defects have resulted in a lack of security, safety, health, well-being, and social value for households and the wider community.

The idea that the residential construction industry delivers products to consumers rather than being a consumer-focused industry is not new. Nor is it new to conceptualise the residential construction sector as one characterised by supplier-induced demand. Oswald and Moore's book goes beyond simply challenging the residential construction sector's claim of consumer responsiveness. Their research shows a much darker, deeper, and pervasive seam of consumer abuse in which the lives and economic security of owner occupiers, tenants and investors in residential property are put at risk through a range of building defects.

Oswald and Moore provide a compelling charting of under-performance, manipulation, and lack of accountability by key actors in the residential construction industry. While focused on Australia, the book demonstrates a 'crisis in the residential construction sector' that is actually international in scale. Such crisis is evident in a range of countries: China, Columbia, the US, South Korea, Italy, India, Dubai, New Zealand, and the UK. In all these places, dangerous construction and materials defects have been implicated in catastrophic fires, building collapse, buildings that destroy the health of occupants and trades, and residential buildings degraded by poorly controlled moisture.

Many of the examples Oswald and Moore cite are dramatic failures often portrayed in the media. This is particularly the case when dangerous defects generate building failures in multi-unit residential buildings where numerous households in a single location find their lives devastated. The media coverage associated with these building failures may or may not portray these incidents as systemic. The authors, however, are clear that they are. These incidents are not simply representative of widespread failures of individual designers or builders. These defects arise across multiple dimensions of construction sector practices including problems with design, issues with materials, failure to build according to consented or approved plans, fidelity to plans, and poor workmanship.

One of this book's strengths is its analysis of dangerous defects, which goes beyond consumer taste or buildings with irritating, but minor, deficiencies. The authors argue that the failure to differentiate between dangerous defects and minor, often cosmetic, defects can act as a barrier to construction industry improvement. Dangerous defects may be observable during construction, but their appearance is frequently during completion and handover. When dangerous defects become apparent after that transfer, the ability to ensure that builders and developers rectify those defects is limited.

Examples of dangerous defects are chronicled across different building systems and at different scales, from catastrophic events to insidious problems that may only become evident over time. The authors demonstrate that the scale and prevalence of dangerous defects such as cracks, cladding flammability and integrity, and defects in structural elements associated with partial or total collapse is widespread. These failures are evident across residential typologies, although their impact on life threat, occupants wellbeing and financial security has even more implications in multi-household buildings than for single unit dwellings. For instance, the book extensively discusses how the Grenfell fire prompted reviews of aluminium cladding specification and use in a multiplicity of countries.

That these dangerous defects may not become evident in the short term is one of the reasons why their impacts can be so profound for consumers and occupants. Some defects have adverse impacts on occupant's health and wellbeing, which emerge only slowly. As the authors show, asbestos use, including 'asbestosfluf', in more than a thousand homes in Canberra and New South Wales between 1968 and 1979 is an example of such insidious risk. It took decades to recognise, even longer to remove from the repertoire of industry materials, and even longer to provide support for those adversely affected financially, left in housing precarity, or with poor health.

Establishing who is responsible for the defects and their remediation becomes increasingly complex and attenuated. The authors provide a series of examples and case studies showing the difficulties associated with multiple and elaborate sub-contracting arrangements, issues of design liability, and issues around the performance of a multiplicity of the materials and building systems used in modern buildings.

Accountability and remediation are further complicated by company and project structures used as vehicles by the construction sector and investors. Special project vehicles and company liquidation can both make establishing accountabilities and ensuring remediation problematic. Some jurisdictions have explicitly moved to reduce gaming around liabilities. Oswald and Moore note that voluntary liquidations specifically to avoid liabilities (i.e. 'phoenixing') has long been illegal in Australia, but proving that voluntary liquidations have been undertaken with that intent has been difficult. Australia enacted new legislation to clarify illegal 'phoenixing' in 2020.

Phoenix companies are a legal mechanism in several countries and can be a persistent barrier to seeking effective remedies where building defects become apparent. A company responsible for building defects is abandoned and then an alternative company (without the liabilities) is created. This has been clearly evident in research cited by Oswald and Moore focusing on the 'leaky building' experience within New Zealand's residential sector over the last three decades or so. While law changes are currently being proposed in New Zealand, developers, designers, material producers, and building companies avoiding this type of liabilities have had other undesirable consequences, particularly in the context of housing under-supply. Litigation around residential building failures have tended to embroil building inspectorates, usually in local councils. Local governments have increasingly seen themselves as 'the last man standing' and unfairly at risk of both the costs of litigation and compensation. Some argue that this has prompted a slow, conservative, and, sometimes, costly approach by councils to building consents and code compliance for completed builds.

Oswald and Moore's analysis suggests that the proliferation of dangerous defects and events by which they become revealed are tied to a raft of developments within the construction sector, financing, and regulation. Those include the development of new materials and the globalisation of their use. Unsurprisingly, expanded polystyrene and aluminium composite panels used for cladding are given significant attention. The combustibility of those products is used to highlight other materials (extruded polystyrene, high pressure laminates, polyurethane foam insulation, and polyvinyl chloride additives in biowoods) that may present flammability risks.

If anything illustrates the dynamics of moral hazard, it is the crisis around building defects that Oswald and Moore describe. The impact of dangerous defects spill-over and leave a legacy of risk and exposure which compromises the dwelling stock over extended periods of time. Not only is this a moral hazard, but shows how the construction sector can generate negative social value. For example, stigmatisation in New Zealand has reduced the sale price of dwellings using designs and materials associated with 'leaky building' syndrome, even when there is no evidence that a particular dwelling is affected.

The implications of this book are profound. The authors argue for strengthening consumer protection. From my perspective, dangerous defects arise from poor regulation or poor exercise of regulated powers on industry practices, design and materials. This rich and challenging research by Oswald and Moore demonstrates the need to build well and the wider consequences of not doing so. The book deserves to be read and discussed widely within industry, government, and civil society. It can help to initiate change by understanding the social and economic costs to society of dangerous defects. The nature of these changes implies a radical rethink is needed: clarity on oversight and monitoring, responsibilities, regulation, enforcement, and recourse/resolution when things go wrong.Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Energy sufficiency, space temperature and public policy

J Morley

Living labs: a systematic review of success parameters and outcomes

J M Müller

Towards a universal framework for heat pump monitoring at scale

J Crawley, L Domoney, A O’Donovan, J Wingfield, C Dinu, O Kinnane, P O’Sullivan

Living knowledge labs: creating community and inclusive nature-based solutions

J L Fernández-Pacheco Sáez, I Rasskin-Gutman, N Martín-Bermúdez, A Pérez-Del-Campo

A living lab approach to co-designing climate adaptation strategies

M K Barati & S Bankaru-Swamy

Mediation roles and ecologies within resilience-focused urban living labs

N Antaki, D Petrescu, M Schalk, E Brandao, D Calciu & V Marin

Negotiating expertise in Nepal’s post-earthquake disaster reconstruction

K Rankin, M Suji, B Pandey, J Baniya, D V Hirslund, B Limbu, N Rawal & S Shneiderman

Designing for pro-environmental behaviour change: the aspiration–reality gap

J Simpson & J Uttley

Lifetimes of demolished buildings in US and European cities

J Berglund-Brown, I Dobie, J Hewitt, C De Wolf & J Ochsendorf

Expanding the framework of urban living labs using grassroots methods

T Ahmed, I Delsante & L Migliavacca

Youth engagement in urban living labs: tools, methods and pedagogies

N Charalambous, C Panayi, C Mady, T Augustinčić & D Berc

Co-creating urban transformation: a stakeholder analysis for Germany’s heat transition

P Heger, C Bieber, M Hendawy & A Shooshtari

Placemaking living lab: creating resilient social and spatial infrastructures

M Dodd, N Madabhushi & R Lees

Church pipe organs: historical tuning records as indoor environmental evidence

B Bingley, A Knight & Y Xing

A framework for 1.5°C-aligned GHG budgets in architecture

G Betti, I Spaar, D Bachmann, A Jerosch-Herold, E Kühner, R Yang, K Avhad & S Sinning

Net zero retrofit of the building stock [editorial]

D Godoy-Shimizu & P Steadman

Co-learning in living labs: nurturing civic agency and resilience

A Belfield

The importance of multi-roles and code-switching in living labs

H Noller & A Tarik

Researchers’ shifting roles in living labs for knowledge co-production

C-C Dobre & G Faldi

Increasing civic resilience in urban living labs: city authorities’ roles

E Alatalo, M Laine & M Kyrönviita

Co-curation as civic practice in community engagement

Z Li, M Sunikka-Blank, R Purohit & F Samuel

Preserving buildings: emission reductions from circular economy strategies in Austria

N Alaux, V Kulmer, J Vogel & A Passer

Urban living labs: relationality between institutions and local circularity

P Palo, M Adelfio, J Lundin & E Brandão

Living labs: epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value

J Clossick, T Khonsari & U Steven

Co-creating interventions to prevent mosquito-borne disease transmission in hospitals

O Sloan Wood, E Lupenza, D M Agnello, J B Knudsen, M Msellem, K L Schiøler & F Saleh

Circularity at the neighbourhood scale: co-creative living lab lessons

J Honsa, A Versele, T Van de Kerckhove & C Piccardo

Positive energy districts and energy communities: how living labs create value

E Malakhatka, O Shafqat, A Sandoff & L Thuvander

Built environment governance and professionalism: the end of laissez-faire (again)

S Foxell

Co-creating justice in housing energy transitions through energy living labs

D Ricci, C Leiwakabessy, S van Wieringen, P de Koning & T Konstantinou

HVAC characterisation of existing Canadian buildings for decarbonisation retrofit identification

J Adebisi & J J McArthur

Simulation and the building performance gap [editorial]

M Donn

Developing criteria for effective building-sector commitments in nationally determined contributions

P Graham, K McFarlane & M Taheri

Join Our Community

The most important part of any journal is our people – readers, authors, reviewers, editorial board members and editors. You are cordially invited to join our community by joining our mailing list. We send out occasional emails about the journal – calls for papers, special issues, events and more.

We will not share your email with third parties. Read more

Latest Commentaries

COP30 Report

Matti Kuittinen (Aalto University) reflects on his experience of attending the 2025 UN Conference of the Parties in Belém, Brazil. The roadmaps and commitments failed to deliver the objectives of the 2025 Paris Agreement. However, 2 countries - Japan and Senegal - announced they are creating roadmaps to decarbonise their buildings. An international group of government ministers put housing on the agenda - specifying the need for reduced carbon and energy use along with affordability, quality and climate resilience.

Building-Related Research: New Context, New Challenges

Raymond J. Cole (University of British Columbia) reflects on the key challenges raised in the 34 commissioned essays for Buildings & Cities 5th anniversary. Not only are key research issues identified, but the consequences of changing contexts for conducting research and tailoring its influence on society are highlighted as key areas of action.