www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/reviews/handbook-resilient-thermal-comfort.html

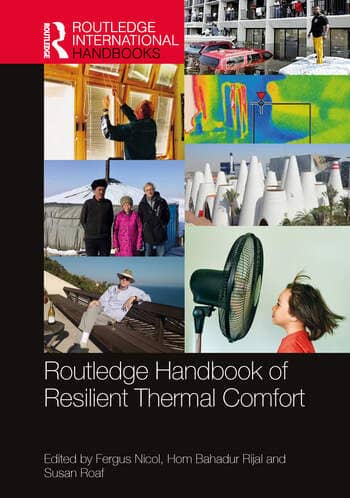

Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort

By Fergus Nicol, Hom Bahadur Rijal and Sue Roaf. Routledge, 2022, ISBN 9781032155975.

Ray Cole reviews this Handbook which captures a breadth of current knowledge on resilient thermal comfort.

The Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal

Comfort is a compilation of works drawn from a wide

range of climatic and cultural contexts and spanning a range of building types

from yurts to houses, offices, schools, and nursing care homes. These contributions

by 91 authors from 20 countries, along with insights drawn from the

editors' long-term involvement in the field, collectively represent an

enormously impressive body of current thermal comfort research. Roaf and Nicol

emphasize why the Handbook focusses on thermal comfort by arguing that the

"temperatures people occupy in their living and working lives can have an

enormous effect on their physical and mental health, well-being and, in turn,

the productivity of individuals, societies, economies and entire political

systems." Moreover, they suggest that the "extent to which societies

experience, avoid or inflict thermal stress on its people and workforce is an

under-recognised measure of their overall humanity" (Roaf and Nicol, 2022).

The Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal

Comfort is a compilation of works drawn from a wide

range of climatic and cultural contexts and spanning a range of building types

from yurts to houses, offices, schools, and nursing care homes. These contributions

by 91 authors from 20 countries, along with insights drawn from the

editors' long-term involvement in the field, collectively represent an

enormously impressive body of current thermal comfort research. Roaf and Nicol

emphasize why the Handbook focusses on thermal comfort by arguing that the

"temperatures people occupy in their living and working lives can have an

enormous effect on their physical and mental health, well-being and, in turn,

the productivity of individuals, societies, economies and entire political

systems." Moreover, they suggest that the "extent to which societies

experience, avoid or inflict thermal stress on its people and workforce is an

under-recognised measure of their overall humanity" (Roaf and Nicol, 2022).

The origin of the Handbook is interesting in and of itself. Roaf and Nicol had been central players in initiating and sustaining a series of 11 international conferences since 1994 that were held in Cumberland Lodge in the Great Park of Windsor Castle, UK. These "Windsor Conferences" uniquely positioned the comfort and health of building inhabitants as a primary responsibility of design professionals, offered a forum for the discussion and development of the science of thermal comfort and its impacts in terms of energy use in buildings, and provided a record of the changing understanding of what is meant by thermal comfort over the past two and a half decades. Moreover, they also positioned these developments within the "rapidly evolving context of building priorities" that evolved from the need to mitigate against climate change through to the "burgeoning challenges thrown at our societies by economic upheavals, ever more extreme weather events and trends" and, more recently, the impacts of the current global pandemic (Roaf, Fergus and Finlayson, 2020).

The last planned gathering in the Windsor Conference series-Windsor 2020: Resilient Comfort-was not possible due to COVID-19 restrictions and the 81 papers were therefore only presented as published proceedings. Many of the 34 chapters in the Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort, evolved from some of these papers together with invited chapters authored by other leading researchers to address two "absolutely key questions in our rapidly heating world"-What is resilient comfort and what are resilient buildings? Presenting such a broad range of thermal comfort research in a single volume is not an easy task, particularly when many of the issues in the chapters overlap. Here, the chapters are organised in 10 "parts" covering topics such as those focussing on specific inhabitant groups: Part III: Sleep and comfort for the old and young, specific building types; Part V: Resilience and comfort in offices, and the recent pandemic; Part IX: COVID: transmission and trust.

While the Handbook unquestionably represents an invaluable resource for researchers, students and others directly engaged in thermal comfort research, several chapters also offer broader reviews that provide a necessary historical context for those less familiar with the significant developments in comfort provisioning that unfolded over the past few decades. Readers therefore benefit from the accumulated knowledge and wisdom gained through the Windsor Conference series.

The thermal comfort conditions in buildings deemed desirable or acceptable have a history of reassessment as have the technologies by which they are achieved. The Handbook sets thermal comfort in an increasing "warming world" and the greater sense of urgency that has emerged to make the built environment more resilient to thermal stresses created by a changing climate. Here, the editors emphasise that "there are no magic solutions for building resilience, but every part of our built environment must be painstakingly rethought in preparation for the thermal onslaught ahead. If you think that the situation today is bad enough with heat domes, drought, fires and ice storms, wait till 2050" (Nicol, Rijal and Roaf, 2022). Of course, given the competing pressures on low-income households, in addition to difficulties in remaining cool during hot spells, many will also not be able to spend the amount needed to stay warm during the winter months and suffer discomfort and the risk of adverse health effects. Fuel poverty will no doubt be further exacerbated by the recent political tensions resulting from Russia's invasion of Ukraine and ramifications on the cost of energy and global food supply.

Unsurprisingly, mandated

comfort standards, and the research that underpins them have been critical in

shaping comfort provisioning in buildings. Of particular interest is the shift from

laboratory-based studies to field-based studies, the supplanting of a steady,

physics-based approach by adaptive thermal comfort models, and the

demonstration of qualitative differences in the experience of thermal comfort

across disparate cultures and climates, such as those in Brazil, Japan, and the

UK. As evidenced in the Handbook, this unfolding story is far from

complete, and thermal comfort research and standards will be reframed again as

the world heats and lifestyles and working patterns change. Khattak, Wright and

Natarajan (Chapter 24), for example, report on the rapid growing worldwide demand

for mechanical cooling and argue that this, in part, is "determined by a dated

and inflexible interpretation of current standards." They examined a "flexible

thermal comfort approach" where building zones are conditioned in "cycles of

cooling followed by an upward temperature drift" resulted in both acceptable

thermal comfort and significant energy savings.

Thermal comfort

"resilience" carries the implication that buildings lacking passive

capabilities may be unable to remain habitable during extreme weather events

and/or power outages caused by climate change. Indeed, Nicol (Chapter 1) argues

that resilience is "about helping populations to survive in a heating

world; it is about protecting people in the buildings where they live and work,

against rising and unpredictable energy costs, ever more extreme weather events

and infrastructural failures [emphasis added]" (Nicol, 2022). Building design

professionals are likely aware of technical "resilience" and

"adaptation" strategies to both prevent damage and to recover from damage created by

increasing frequency and intensity of extreme

disruptive events associated with climate change. Importantly, however, the

Handbook focusses on how buildings and their inhabitants can be

more resilient.

Here, Schweiker (Chapter 2) provides a "holistic

view to human-building resilience" that includes human resilience and its

influencing variable such as "toughness", "ability to cope" and "capacity to

recover" (Schweiker, 2022). Rather than solely a technical issue, the chapters

in the Handbook collectively point to a different role that buildings

must now serve beyond ensuring that their inhabitants are comfortable. Supporting

their ability to make appropriate adaptations and changes to survive in many of

them, even in extreme conditions, will likely gain prominence.

The Handbook

advocates passive design strategies and those that

facilitate behavioural adaptation, rather than the current dependence of thermal comfort provisioning by

air-conditioning and other technologies that

increase building operational energy and associated GHG emissions. This, of

course, is not a new message but one that clearly requires being continually

emphasised until building design professionals embrace climate-responsive approaches.

Casting comfort provisioning within the increasing need for safe conditions in

buildings during temperature extremes and power outages may help trigger change.

Moreover, perhaps unsurprisingly, protecting the health of building inhabitants

from the transmission of the COVID-19 virus is positioned alongside thermal

comfort. Here, given that natural ventilation can reduce the infection rate,

openable windows are strongly advocated. Thus, the confluence of effects of

climate change being felt and the COVID-19 pandemic have provided further weight

to the need for a greater deployment of passive strategies.

"Human agency" - the capacity of individuals to act independently and to make their

own free choices - is presented as central to resilient comfort: the range

of adaptive behaviours and opportunities for inhabitants to alter their own

thermal conditions; and the extent of their ability to interact with building

interfaces or to employ those adaptive opportunities available in buildings. Unlike automated control systems,

building inhabitant's agency enables them to manage risk and take advantage of

opportunities. Indeed, drawing on a number of published studies, Heschong and Day (Chapter 3) concluded that "[w]e may need to

rethink how we use technology and automation in buildings, using them more as

tools to enrich the occupant experience, and enable occupant agency and

control, rather than restricting and devaluing occupant interaction with the

building" (Heschong and Day, 2022).

Given the wide range of authors, differences in language are to be

expected. Various chapters in the Handbook, for

example, use either "occupants" or "inhabitants" of buildings, with the

former most common. However, the emphasis on agency would suggest that "inhabitants" more accurately captures

the active participation and potential agency of building users with building

systems than the term "occupant" used in conventional comfort research to

portray a passive recipient of universalized comfort standards.

The comprehensive body of research that

the editors have complied in the Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort collectively

provides a wealth of constructive insights and lessons for the design of more

resilient buildings. It justifies the importance of supporting greater

inhabitant agency. Although these represent the central focus, this volume points

to a much broader perspective on the roles and responsibilities of building

design professionals and therefore provides them with a valuable resource. As a handbook, they may selectively

review those chapters of more direct relevance to their interests. The

electronic version, and its attendant search capability, is particularly

useful for this.

While the Handbook was published in 2022, the research in the constituent chapters would have obviously been conducted a year or more earlier and several new developments have unfolded subsequently. Although the global pandemic may be subsiding, the economic fall-out, the disruption of supply-chains, the changing nature of work and way that buildings are used, and the straining of social systems, present a different context in which to understand thermal comfort. Irrespective of how the future unfolds, the Handbook provides tangible evidence of coupling inhabitant behaviour and thermal comfort resilience with building capability and building resilience.

References

Heschong, L. and Day, J.K. (2022). Why occupants need a role in building operation: a framework for resilient design, IN: Nicol, F., Rijal, H.B., and Roaf, S. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort, Routledge.

Khattak, S.H., Wright, A. and Natarajan, S. (2022). Flexible future comfort, IN: Nicol, F., Rijal, H.B., and Roaf, S. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort, Routledge.

Nicol, F. (2022). The shapes of thermal comfort and resilience, IN: Nicol, F., Rijal, H. B., and Roaf, S. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort, Routledge.

Nicol, F., Rijal, H.B., and

Roaf, S. (2022). Preface, IN: Nicol, F., Rijal, H. B., and

Roaf, S. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort, Routledge.

Roaf, S., Nicol, F. and Finlayson, W. (Eds). (2020). Windsor Conference 2020: Resilient Comfort Proceedings. ISBN 978-1-9161876-3-4. https://windsorconference.com/proceedings/ Windsor 2020

Roaf, S., and

Nicol, F. (2022). Resilient comfort standards, p. 585, IN: Nicol, F., Rijal, H.B., and Roaf, S. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort, Routledge.

Schweiker, M. (2022).. Rethinking resilient thermal comfort within the context of human-building resilience, 23-38, IN: Nicol, F., Rijal, H.B., and Roaf, S. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Resilient Thermal Comfort, Routledge.

Latest Peer-Reviewed Journal Content

Acceptability of sufficiency consumption policies by Finnish households

E Nuorivaara & S Ahvenharju

Key factors for revitalising heritage buildings through adaptive reuse

É Savoie, J P Sapinski & A-M Laroche

Cooler streets for a cycleable city: assessing policy alignment

C Tang & J Bush

Understanding the embodied carbon credentials of modern methods of construction

R O'Hegarty, A McCarthy, J O'Hagan, T Thanapornpakornsin, S Raffoul & O Kinnane

The changing typology of urban apartment buildings in Aurinkolahti

S Meriläinen & A Tervo

Embodied climate impacts in urban development: a neighbourhood case study

S Sjökvist, N Francart, M Balouktsi & H Birgisdottir

Environmental effects of urban wind energy harvesting: a review

I Tsionas, M laguno-Munitxa & A Stephan

Office environment and employee differences by company health management certification

S Arata, M Sugiuchi, T Ikaga, Y Shiraishi, T Hayashi, S Ando & S Kawakubo

Spatiotemporal evaluation of embodied carbon in urban residential development

I Talvitie, A Amiri & S Junnila

Energy sufficiency in buildings and cities: current research, future directions [editorial]

M Sahakian, T Fawcett & S Darby

Sufficiency, consumption patterns and limits: a survey of French households

J Bouillet & C Grandclément

Health inequalities and indoor environments: research challenges and priorities [editorial]

M Ucci & A Mavrogianni

Operationalising energy sufficiency for low-carbon built environments in urbanising India

A B Lall & G Sethi

Promoting practices of sufficiency: reprogramming resource-intensive material arrangements

T H Christensen, L K Aagaard, A K Juvik, C Samson & K Gram-Hanssen

Culture change in the UK construction industry: an anthropological perspective

I Tellam

Are people willing to share living space? Household preferences in Finland

E Ruokamo, E Kylkilahti, M Lettenmeier & A Toppinen

Towards urban LCA: examining densification alternatives for a residential neighbourhood

M Moisio, E Salmio, T Kaasalainen, S Huuhka, A Räsänen, J Lahdensivu, M Leppänen & P Kuula

A population-level framework to estimate unequal exposure to indoor heat and air pollution

R Cole, C H Simpson, L Ferguson, P Symonds, J Taylor, C Heaviside, P Murage, H L Macintyre, S Hajat, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Finnish glazed balconies: residents' experience, wellbeing and use

L Jegard, R Castaño-Rosa, S Kilpeläinen & S Pelsmakers

Modelling Nigerian residential dwellings: bottom-up approach and scenario analysis

C C Nwagwu, S Akin & E G Hertwich

Mapping municipal land policies: applications of flexible zoning for densification

V Götze, J-D Gerber & M Jehling

Energy sufficiency and recognition justice: a study of household consumption

A Guilbert

Linking housing, socio-demographic, environmental and mental health data at scale

P Symonds, C H Simpson, G Petrou, L Ferguson, A Mavrogianni & M Davies

Measuring health inequities due to housing characteristics

K Govertsen & M Kane

Provide or prevent? Exploring sufficiency imaginaries within Danish systems of provision

L K Aagaard & T H Christensen

Imagining sufficiency through collective changes as satisfiers

O Moynat & M Sahakian

US urban land-use reform: a strategy for energy sufficiency

Z M Subin, J Lombardi, R Muralidharan, J Korn, J Malik, T Pullen, M Wei & T Hong

Mapping supply chains for energy retrofit

F Wade & Y Han

Operationalising building-related energy sufficiency measures in SMEs

I Fouiteh, J D Cabrera Santelices, A Susini & M K Patel

Promoting neighbourhood sharing: infrastructures of convenience and community

A Huber, H Heinrichs & M Jaeger-Erben

New insights into thermal comfort sufficiency in dwellings

G van Moeseke, D de Grave, A Anciaux, J Sobczak & G Wallenborn

'Rightsize': a housing design game for spatial and energy sufficiency

P Graham, P Nourian, E Warwick & M Gath-Morad

Implementing housing policies for a sufficient lifestyle

M Bagheri, L Roth, L Siebke, C Rohde & H-J Linke

The jobs of climate adaptation

T Denham, L Rickards & O Ajulo

Structural barriers to sufficiency: the contribution of research on elites

M Koch, K Emilsson, J Lee & H Johansson

Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation [editorial]

V Castán-Broto, M Olazabal & G Ziervogel

Nature for resilience reconfigured: global- to-local translation of frames in Africa

K Rochell, H Bulkeley & H Runhaar

How hegemonic discourses of sustainability influence urban climate action

V Castán Broto, L Westman & P Huang

Fabric first: is it still the right approach?

N Eyre, T Fawcett, M Topouzi, G Killip, T Oreszczyn, K Jenkinson & J Rosenow

Social value of the built environment [editorial]

F Samuel & K Watson

Understanding demolition [editorial]

S Huuhka

Data politics in the built environment [editorial]

A Karvonen & T Hargreaves

Latest Commentaries

Decolonising Cities: The Role of Street Naming

During colonialisation, street names were drawn from historical and societal contexts of the colonisers. Street nomenclature deployed by colonial administrators has a role in legitimising historical narratives and decentring local languages, cultures and heritage. Buyana Kareem examines street renaming as an important element of decolonisation.

Integrating Nature into Cities

Increasing vegetation and green and blue spaces in cities can support both climate change mitigation and adaptation goals, while also enhancing biodiversity and ecological health. Maibritt Pedersen Zari (Auckland University of Technology) explains why nature-based solutions (NbS) must be a vital part of urban planning and design.